SGU Episode 525

| This episode needs: proofreading, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 525 |

|---|

| August 1st 2015 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

"Science has taught me (Science warns me) to be careful how I adopt a view which jumps with my preconceptions, and to require stronger evidence for such belief than for one to which I was previously hostile.My business is to teach my aspirations to conform themselves to fact, not to try and make facts harmonize with my aspirations." |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

- Jay identifying blaster sounds

- Steve, Bob, and George Hrab went to see Ant Man together

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Thursday, July 30th, 2015, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Hey guys.

S: Jay Novella...

J: [blaster sounds]

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Oh, my God, I've been shot.

S: You're busting out over there, Jay. What's going on?

J: The Star Wars movie is coming out. I'm not going to pretend that I'm not celebrating and getting super excited.

E: Only 130-something days till...

J: Yep, I bought a blaster a few weeks ago. That means I have three super awesome high-end blasters.

B: Jay, that sound effect was awesome. Where'd you get that?

J: Actually, Bob bought me a little sound effect machine for my birthday.

C: Oh, how fun.

J: That sound is embedded in my DNA.

C: Does it only make spacey sounds?

J: It's all the blaster sounds from Star Wars, Cara.

C: Gotcha.

J: Which you clearly don't know, and I will have to educate you.

C: Nope, not at all. You can identify each of those sounds?

S: Oh, yeah.

'C:ou're such a nerd. I love it.

J: Do we do it?

E: He knows if it's left-handed or right-handed.

J: No, but I swear to God, when Bob gave it to me, me, Bob, and Steve were together, and I was telling Bob, like, I know all of them. And I'm like, I click it, and I named it. I clicked it, and I named it. And I clicked it, and I named it. And Steve's like, oh, no, no, that one was this one. And he was like, oh, yeah, yeah, you're right. We had to make a minor edit. I was right, but it was slightly off. So the details are incredible. I mean, I could picture the thing shooting it. Like, one of them is the ion cannon. One of them is a stormtrooper blaster. One of them is the sound that a snowwalker's gun makes. Yeah, I have them all memorized.

B: Yeah, it was impressive.

C: You're like one of those guys who can say what the hot rod is when he just hears it on the road.

J: Exactly. Except much cooler, I can identify blasters.

S: No, it's funny. We went to see Ant-Man over the weekend.

J: It was George.

S: George Hrab was with us. And we saw our first in-the-theater Star Wars preview.

E: Oh, yes.

S: George was sitting between Bob and I. And when, like, the Lucasfilm thing came on the screen, and we realized that it was a Star Wars preview, Bob and I both gasped at the same time. On either side of George, we're like, oh. And George just started cracking up.

B: He was laughing.

S: Nerdgasm in stereos.

C: How was Ant-Man, though? Did you guys like it?

S: It was solid.

B: We all enjoyed it. It was fun. Just a fun romp. And I don't think nobody had a problem with it.

E: It carried its weight.

C: Nice.

S: All right. Let's get going. We have a great interview with Kevin Folta coming up later in the show.

Forgotten Superheroes of Science (3:03)

- Gerty Cori: The first woman to win a Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, for elucidating the metabolism of glucose in the human body

S: But first, Bob, you have your Forgotten Superhero of Science.

B: Yes! For this week's Forgotten Superheroes of Science, I'm covering Gerty Cori (1896 to 1957). She was a biochemist who was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. She and her husband shared half the prize for elucidating the metabolism of glucose. Ever hear of her?

S: I've heard of glucose.

B: Probably not! Yeah.

S: Glucose metabolism.

E: I've heard of Galloping Gerty, but...

B: I feel a little bit like a broken record, because this is the point where I cover the problems that these women had decades ago, being a scientist. So, typical for women of her time, Cory had a difficult time procuring jobs in her field. And even when she did get a job, the pay was crap. It was really pathetic. One thing I find that was interesting, even after they had made their big discovery, and her husband and she were looking a job. One university actually told them that it was un-American for a husband and wife to work together.

E: Okay.

B: Un-American. They said that his career would suffer, even after their major discovery, Mr. Cory would get jobs very easily, but she was offered salaries that were one tenth of his, even though they were equal partners in the lab. So yeah, it was really pathetic. We've come a long way, although we're not where we need to be. But we've definitely come a long way. So she and her husband did their major work at the State Institute for the Study of Malignant Diseases. Sounds so cool. That's now called a Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Now, they investigated, like I said, carbohydrate metabolism in humans, and the hormones that regulate it. So in 1929, they outlined the biological cycle that describes the breakdown of the carbohydrate glycogen in the muscles to make glucose for energy, and lactic acid. And lactic acid is causes that burning sensation if you're lifting weights in your muscles. They also figured out how that lactic acid is converted back into glycogen by the liver for later storage in the muscles. So this is how the body produces and stores energy. Pretty fundamental stuff. Very, very important. And this cycle that I've been talking about became called the Cory Cycle, named after both of them. And it won them the Nobel Prize in 1947. And she was the first American woman to win a Nobel. So that was quite a milestone. Their discovery contributed to our understanding and treatment of diabetes and other metabolic diseases. But not only was the Cory Cycle named for them. But the Cory Crater on the Moon, and the Corty Crater on Venus are named, also. And I believe after Gerty specifically. See, now I'm thinking about the SGU crater, but we'll address that in a future episode. So, remember Gerty Cory; mention her to your friends, perhaps when discussing gluconeogenesis, and the conversion of lactate into pyrovate.

C: Yup. I'm always talkin' about that with my friends.

B: Yep, it comes up. It comes up.

S: I have actually had that conversation, but...

(Laughter)

J: That's awesome, Steve.

E: But they weren't really a friend, were they.

S: Well, you know, classmates. All right.

J: That's awesome.

News Items

EM Drive Revisited (6:09)

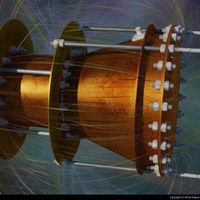

S: Evan, I understand that the propellant-less EM drive is back in the news.

B: Ah, why?

E: It is back in the news. With the Apollo space mission successfully sending people to the Moon late 60s and the 70s. Well, how long did it take to get to the Moon in those days? Do you remember, Bob?

B: You mean to fly there?

E: Yeah, fly there.

S: With the Apollo mission?

B: It was three days. Three days.

J: Yeah, three days.

E: Three days to reach the Moon. That's exactly right. Now, how long did it take the New Horizons probe to get to the Moon? What, past the Moon?

B: I actually read that.

S: Eight hours, I think.

B: It was very impressive. It was far less than a day. Far less than a day.

E: Eight and a half hours. Exactly. Good job, Steve. You remembered. And they just strapped that to a bed of rockets, hurled it into space, and off it went. But what if I told you that these scientists working alone in a basement in Germany somewhere have developed a space drive system which could reach the Moon in a mere four hours? Could it really be true?

C: I don't believe it.

S: Ah, you close-minded skeptics. Trying to crush innovation and dreaming, how dare you?

E: If you've read about the EM drive in the past several years, and it has been discussed before, these engineers have been working on this, an electromagnetic drive that will work by bouncing a bunch of microwaves within its container around. And like you said, Steve, no propulsion, yet there it goes.

S: No propellant.

E: No propellant, yes. Here's the most recent news on this right now. Scientists have finally confirmed that the EM drive actually works, and that more robust tests of the drive system are coming. That's incredible, and it's also a bunch of crap.

S: Yeah.

E: But that is the news that's making the rounds right about now. So here's the main critique. It's this insurmountable thing to overcome by the EM drive proponents is that the system produces thrust without a propellant. That's considered a violation of the laws of physics, specifically the one having to do with conservation of momentum.

S: Those conservation laws, man, they are...

E: Pesky.

S: Yeah, they are uncompromising.

B: Inconvenient.

S: The device allegedly works by bouncing microwaves back and forth within its chamber, and there's this subtle asymmetry to it bouncing harder in one direction than the other, and that produces thrust of some sort. But the engineers really don't have a good hand on exactly why it moves, why it creates the thrust. It's got to be quantum something or other, right?

C: And does it go in a specific direction, or does it just kind of like fall over?

S: It produces thrust in a direction, yes.

C: In a direction.

E: Steve, I know you wrote about this in a blog post, and certainly a lot of scientists have chimed in on this as well. Not only the feasibility of it is not there, but there are also some other problems with this.

S: Yeah, this is basically the equivalent of cold fusion or free energy, right? Where you have a machine that apparently breaks a well-established law of physics. And the research that's showing this effect, the effect size is minuscule, right? We're talking micronewtons. I hear conflicting things reading around. You know, some people are saying this is within the noise of the error of the devices doing the measurement. Other people have claimed that the error is less than the measurement. But when I wrote about it, I linked to a good article that quotes many physicists and scientists who looked at the—the paper's not peer-reviewed, but it's been released so you could read the paper. And they were very critical. For example, one physicist noted that the thrust sort of lags when you turn the machine on and off, right? When you turn the machine off, the measured thrust doesn't go off right away. It sort of fades away, which is consistent with heat. Yeah, so it's like—yeah, as it heats up, the apparent effect occurs. And then you turn it off, and then as it slowly cools down, the effect goes away. So that sort of screams artifact. You know, it doesn't go away when you turn it off. They also said that, yeah, that heat actually throws off the measuring device. So it could just be that the error goes up as the heat goes up, you know? So there's lots of things that have not been eliminated by this test. What's interesting is that the author, Martin Tajmar, who writes in the conclusion, our test campaign cannot confirm or refute the claims of the EM drive. They say that they didn't confirm that it works right in the conclusions. Just that, yeah, we measured some anomalous thrust, and we can't figure out where it's coming from. But they didn't really confirm that the thing is working, despite the fact that that's how it's being reported. You know, that they confirm that it works. They said it. They're not confirming that it works. You know, the reporting on this has been so gullible and so terrible.

C: Yeah, welcome to writing for the headline. Gosh.

E: Exactly right.

S: But even worse, I have to say, I posted this on our Facebook page. I know I'm not supposed to read the comments on our Facebook page. But I knew we were going to be talking about this tonight, so I wanted to see what people were saying about it. And my God it's obvious that most people are commenting by the headline of our Facebook post and didn't actually read my article. Because they make comments that I address in the article. It's like, seriously, I didn't say that. Either that or their reading comprehension is so blinkered by they just want to think that this thing is real or they start to get on their high horse about let's stop being very skeptical to be dismissive. Dude, this is implausible. I'm just saying it's implausible. It's about as plausible as cold fusion or free energy.

E: Homeopathy.

S: And the results here are razor thin. They're well within the noise. Scale this freaking thing up before you make any claims about it. And the scientific, I mean, I'm just quoting the scientific community who are more dismissive than me, that I was being directly there's like Sean Carroll said, this is a total freaking waste of time. I will focus my research on something that's real.

E: I'm going to spend my time thinking about ideas that don't violate conservation of momentum.

S: Yeah, that's what scientists, people who actually understand physics, you should probably take them seriously.

C: This is such a frustration with science journalism or not just science journalism, any journalism and how we consume journalism. I get so frustrated by people. It's a common device to make your headline something like, is the moon made of cheese? And then, of course, the very first line of the article is like, no, no, it's not made of cheese. But nobody reads the article. They just feel the need to comment on the headline.

S: Right, right.

C: And also, I mean, I remember having a real frustration back when I was at HuffPost, because what some people don't realize is that a lot of journalists don't get to write their own headlines.

S: Yeah.

C: And so I wrote about the Higgs boson and I had this whole part in it about how I hate that it's called the God particle, because that's really a bastardization of the goddamn particle because it was so hard to find. And I actually went on like a diatribe, chiding journalists for calling it the God particle because I had a really just I really had a hard time with that name. And so in the middle of this piece there's this long rant. You find it on the homepage and it's titled God Particle Discovered.

B: Oh, God.

S: All right. Well, let's move on to the next item.

Hope for Malaria Vaccine (13:53)

S: Cara, you're going to tell us about hope for a new malaria vaccine.

C: I am. I'm actually really, really excited about this. It's not necessarily the newest of stories, but there was progress was made recently because this malaria vaccine has been in development by GlaxoSmithKline for years, for a very, very long time. But today there was not really a ruling, but a statement that was made by the European Medicines Agency. This is sort of like the EU's answer to the FDA. And so they make statements about the safety of drugs, about their utility. And they went ahead and said that they think that this vaccine should be used. And based on that, now the World Health Organization is going to assess this vaccine candidate and their decision will ultimately affect whether or not young children in Sub-Saharan Africa get this malaria vaccine. So to back up a little bit, it's called Mosquirix. That's the brand name. So you might start hearing about that, Mosquirix. Its sort of clinical name is RTSS. So that's the shorthand that you'll sometimes hear. And it was given to 16,000 young children in 13 African research centers in Sub-Saharan Africa. So from Gabon to Kenya to Ghana to Nigeria to Tanzania. And these kids were very, very, very young. The problem with vaccine with this vaccine is that typically when you're in a clinical trial, you're looking for at least 50 percent efficacy, if not closer to 90 plus percent efficacy. And they just don't have that with this vaccine. So this is wherein lies kind of the conundrum, I think, for the researchers and also for the regulatory agencies. It says that at the end of the trial, there were four doses of the vaccine given, three a month apart and then a booster 18 months later. At the end of the trial, the vaccine reduced malaria cases by 39 percent in children age 5 to 17 months and by 27 percent in infants. And that was after three years. So here's the question. You know, it's not fully effective. Is it worth the risks that come along with vaccines? Is it worth the expense? Is it worth having to deliver four doses of this vaccine knowing that it only has a reduction in malaria of between 25 and 40 percent? Well, the European agency says, yes, it is worth it. And now it's up to the WHO or the World Health Organization to decide, because whatever they decide will actually affect whether certain nations are required to start providing those vaccines.

S: That relates to another item that I wrote about recently where scientists were looking at vaccines and they found that for imperfect vaccines, vaccines that do not provide essentially enough resistance to the disease that it prevents spread of the disease, what they call a leaky vaccine you still get the infection, you still pass it on, but you'll survive the infection. And they were specifically looking at a viral infection in chickens, a herpesviral infection. There's a vaccine for that. There used to be a huge problem in poultry industry and now basically all the chickens get vaccinated and so it's not a problem anymore. But they found that this vaccine can cause or increase the occurrence of more virulent strains of the virus. It's like a bacteria developing antibiotic resistance. You know, the viruses that are more virulent and can spread despite the vaccine are the ones that predominate over time. The solution, just like with antibiotics, is thorough coverage. So if everyone gets vaccinated, then it's not an issue. Or if you have a non-leaky vaccine, it's not an issue. It's only an issue for, quote unquote, leaky vaccines. And the reason I bring it up is because they specifically mentioned that malaria is a difficult disease to vaccinate against. You get this imperfect result and that's the kind of leaky vaccine that we have to be careful about because it actually could make the infecting organism more virulent.

C: Yeah, for sure. I mean, we're not getting anywhere close to typical results with what we think of as a traditional vaccine, which generally speaking is for viruses. There are also some vaccines for bacteria now, but this vaccine would be the first ever vaccine for a parasite. You know, malaria is caused by plasmodium. So it's a totally different life cycle. It's a totally different functionality. And what it really does, the vaccine sort of boosts the immune system of the person so that they resist the parasite before it can go in and infect the liver, which is when most people get sick. The parasite infects the liver and then it spreads out into the blood and you start to get a lot of damage to red blood cells. And that's where you get those terrible, terrible, we call them here in the West, flu-like symptoms. But in a lot of parts of the world, they actually call them malaria-like symptoms.

J: Yikes. Wow.

C: Yeah, it's just horrible. And you have these children that are getting malaria three, four times a year. You've got death rates hanging around the half a million point for the last many years. And is it worth it? You know, to me, and who knows? I'm definitely not an epidemiologist. I have no idea. It seems like, man, if we can even prevent a few of these cases, maybe we should. And that also seems to be the opinion of this medical agency in the EU. But time will only tell whether the World Health Organization says the same thing. And even then, it might not be available in significant doses to the individuals who need it until 2017. I will say, as a random follow-up and maybe a little piece of good news, as I was researching this story, I also read that as of this week, Nigeria has now been polio-free for one year. Which is just a huge, huge accomplishment. And get this. I found this crazy statistic. In 1988, there were 125 countries harboring polio. Now that Nigeria has reached total eradication, which technically they haven't yet because it has to be measured, I think, four or five years out. But once they do, there will only be two countries remaining, Pakistan and Afghanistan, that have any cases of polio. This could be a disease that is fully eradicated from the planet. And the only other disease we know that we've done that is is smallpox.

S: In humans.

J: So is that possible, though? Like, I thought I read somewhere that if we vaccinated a disease, quote unquote, away where nobody actually had it, that it doesn't mean it's gone from the ecosystem.

C: Yeah, it's not. It might still be in a reservoir. You know, it's like, this is a big problem with things like Ebola, which, yeah, we don't have a vaccine for Ebola, but Ebola just goes away. Usually, it pops up in a very small area, and then it just goes away. The problem is it exists in a reservoir. There are animals that carry it. And then you have these, what they call spillover events, this kind of zoonotic infection that comes from an animal into a human. And that can happen with viruses. It's probably how most viral infections, or I should say many, not most, but many viral infections started. But if we can prevent it, and if we still have enough vaccine on hand, let's say that there was another spillover event, we'd be able to contain it immediately.

S: Yeah, but, Jay, polio does not have a non-human vector.

C: Oh, it doesn't? See, that's even better.

S: Polio is a virus that can be eradicated. Smallpox, no non-human vector. That's why we were able to eradicate it.

C: That's amazing.

S: We don't talk about eradicating infections that have non-human vectors, because you can't.

C: Because they will pop up.

S: They will survive in the animal vectors. That's right.

B: What if you vaccinated the animals?

S: Well, yeah, but...

C: The wild animals.

S: You're going to vaccinate every bat in Africa or something? It's just not going to happen. It's just not feasible.

J: Well, you won't even try, Steve, huh?

E: Yeah, Steve.

S: Well, unless you come up with some new way of doing it. I mean, it's not impossible. Let's move on.

Cannabis Oil (22:35)

S: Have you guys heard that cannabis oil cures everything?

J: Sure.

C: Oh, yeah. I hear that every day.

J: Yeah, man, yeah.

S: It's good for whatever ails you. There's a study going around where a man claims that he was given... This is the title. He was given 18 months to live, but he illegally cured himself of his cancer with cannabis oil. That's basically the story. So as I like to do, I read the story and deconstructed it a little bit. So first of all, the man in question is David Hibbett. He was diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2012. He was treated with surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. And then he had a recurrence in a lymph node. He was treated with chemotherapy, which shrank the lymph node to the point where it could be removed surgically. Then he said, I'm going to try cannabis oil. And credits his current cancer-free, apparent cancer-free state on the cannabis oil. What do you guys think about that? That's perfectly cromulant. It had nothing to do with all the surgery and chemotherapy and radiation. But also, reading multiple versions of the story and delving into some of the details. So the headlines are, man given 18 months to live. Actually, which I always know is dubious, first of all. We don't tell patients, you're going to die on September 23rd. Yeah, there's a range. It's always a statistical range. And it's purely statistical. And some diseases have what we call a long tail. You could survive, maybe 90% of people will survive for three years. And 5% of people will survive for six years. And then there's decreasing percentages of people survive for longer and longer. And sometimes people survive for a really long time. So if you're at the top 1% of survival, statistically, of a disease, that could mean you're surviving much longer than the 95% typical range that we might tell patients. And of course, you're going to think that you massively out-survived or outlived your prognosis. What if you're in the top 1 in a million of your disease, right? That is a story that's going to be told far and wide, right? And this is why anecdotal evidence is worthless. Because you have no idea how highly selective it is. Anyway, it's even worse than that in this case. So this guy was not told he had 18 months to live. He was told he had between 18 months and five years to live. But they conveniently dropped the five years and just kept the 18 months.

C: And I'm sure it's still within that five-year period, right?

S: Yeah, we're three years into that five-year period. He hasn't even outlived his prognosis yet. But that's lying. That's like...

B: Kind of important, yes.

S: That's beyond distorting it. When you turn 18 months to five years into 18 months, now you're over the line into lying. So again, I have to always emphasize when we talk about these cases that are made public, of course, I hope this guy is cancer-free and lives a long and healthy life. Obviously, I wish nothing but the best for him. But you've made your story public in order to promote snake oil. We've got to address the details of this story, at least as we know them.

C: Well, and that's another thing that pisses me off too. It's like a misuse of a legitimate drug. Cannabis has real quality effects for people who are struggling with cancer.

S: Yeah, it's a drug.

C: It's not going to help the case. It's not going to help the case for decriminalization or for medical usage of this drug for what it can do, which is help you have an appetite and help you sleep at night and all of this if you've got this other group of people saying, oh, it cures everything from cancer to diabetes.

S: Yeah. It's interesting why cannabis has been the focus of so many of these snake oil claims, and probably because there is this existing decriminalization movement, which is a completely separate issue. And again, I'm not commenting about that at all. I'm just saying that people have latched onto this herbalism, snake oil-type claims for it that it can cure anything. But if you just strip away all of the political nonsense and just look at the actual data, it's a drug. It's a drug that has some very interesting effects. It's probably very useful for nausea and appetite, maybe as treating the side effects of chemotherapy, for example. We may develop many other uses out of it. There's a lot of preliminary evidence, basic science, preliminary evidence, and some clinical evidence for these applications. But again, people latch onto every mouse preliminary study and say, it cures this or it helps that. That's where the pseudoscience comes in. But let's look at specifically for cancer. David Gorski, who is our cancer expert on science-based medicine, did an excellent review of the literature. And it's just not that impressive. There's been, first of all, no human trials. There's a number of animal trials for different kinds of cancer. And the bottom line is this. When you're doing an animal study or a Petri dish study, you're looking at the anti-cancer effects of a drug. I'm reminded of that. I think it's an XKCD cartoon where they say, always think of this. And he shows a picture of a scientist holding a gun at a Petri dish. That kills cancer, too. It makes a legitimate point is that it's not, does it kill the cancer cells? It's, how effectively does it kill the cancer cells? Which specifically deals with, are we going to be able to get it into you in a concentration that is sufficiently lethal to cancer cells that you will tolerate? So it's not, does it kill cancer cells? It's just, at what dose does it kill cancer cells? And when you ask that question, it's actually not that impressive. Its effectiveness is actually lower than what we like anti-cancer compounds to be.

C: I'm wondering from you, or I guess from David, but maybe from you through David, do oncologists, do doctors like to talk about cancer in those kinds of terms, like curing?

S: So we talk about remission. Remission is the term we use for a quote unquote cure, which just means that you're cancer-free, there's no detectable cancer, but because it could always come back. So you're like, you're in remission and here are the statistics about staying in remission.

C: Yeah. Okay. Because it definitely seems like everything about this article is woo, that there's obviously no control because he was having legitimate medicine at the same time. The fact that he's still in his prognosis period. But just anytime I read something that says, blah, blah, blah, cure cancer, I'm always like, I don't buy it.

S: Yeah. You have to be cautious about that. I mean, you can use the word cure as a shorthand if you talk about somebody who survived, in remission for a certain amount of time, where basically your risk of recurrence is now down into the background rate of just getting cancer for anybody. So you're effectively cured.

C: I see.

S: That's a reasonable shorthand, but not technically to be true. We talk about in remission, but I don't mind if somebody says, yeah, they've been cancer-free for so long that their risk of recurrence is negligible. Fine. You could call that a cure.

C: Then they're cured.

S: You can call that a cure if you want to. That's fine. That's a reasonable shorthand.

C: I guess I have a hard time with it because it's so common in the general public that people don't fully understand that cancer is more of a process, that it's not one disease. And so I feel like it just confuses things further to talk about potential cures.

S: I do agree with that. And also, there's something that we call the honeymoon period. So the usual course of many cancers, not all, obviously, but is you get diagnosed, you get treated, which could include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy if necessary, whatever, the standard course of treatment. You're done with that treatment, and the cancer is removed or shrunk or whatever. But we don't know if we got all of it or if it's going to come back. You're in the honeymoon phase where anyone can feel as if they're cured because the immediate effects and signs and symptoms of the cancer are gone. But we don't use the term cured because you're still within the period of high risk for recurrence. We don't know if we got it all yet or if the chemotherapy worked, et cetera. And so that's often the phase, though, where people come out and say, I cured myself with this natural, all natural crap because they're in the honeymoon phase. It's easy to make that claim when you're in the honeymoon phase, right? Because everyone feels like they're cured at that point in time, especially if you've had the surgery or whatever. It doesn't really become a meaningful claim until you've survived beyond the bell curve, right? Beyond the survival curve for somebody with your type and stage and et cetera of cancer. But then you often don't hear about them when the cancer comes back two years later.

E: That's right.

S: And also what they do is they'll take the fake natural treatment instead of chemotherapy. And then because they go three or four years without a recurrence, they say that it worked. But with breast cancer, if you have the lumpectomy or surgery, that's 85% right there, right? You're already down to only like a 15% recurrence rate. And then the chemotherapy doesn't really treat the cancer or get rid of the cancer. It just reduces the risk of recurrence. It drops it to like 7%. So somebody who does the surgery but skips the chemotherapy and then takes a natural treatment and feels like that worked, well, you have no idea. Chances are you weren't going to get it back anyway. You're still 85% likely of not having a recurrence, which is great. And that is the pattern that they use to tell their anecdote and convince the public that their natural treatment worked and they did it instead of the standard therapy or instead of chemotherapy. But you have to actually be a physician, hopefully an oncologist, and know how these things normally play out and know the statistics to be able to even interpret what's happening, which is why David Gorski is always writing about this, correcting the record. But it doesn't make for the sexy headlines as man given 18 months to live cures himself with cannabis oil. That's a little bit more exciting.

Washington DC is Sinking (33:12)

S: All right, Jay, I understand that Washington DC is sinking.

E: What are you sinking?

S: So predictable, so predictable.

J: So have you guys ever heard of a four bulge collapse? I know that this sounds like Bob's sex life, but it's actually something important that we should pay attention to. So the latest research has confirmed that the land under the Chesapeake Bay is sinking.

E: You mean the swamp is sinking? Who would have thought that?

J: So this is the bay found, where is it? It's near Washington DC in the United States. The researchers determined that the area of land that DC is located on could drop by more than six inches in the next hundred years. Six inches. So, of course, that would dramatically affect the coastal area. What would it do?

S: Especially if the ocean is rising, it'll exacerbate the loss of the coastline.

J: Yeah, of course. So the shore would creep. It would threaten things like wildlife refuges and, of course, military installations. Yep. And in DC, all those monuments could be washed out. So measurements over the past 60 years that they've been taking have indicated that the sea level in that area has actually been rising two times faster than the average rate compared to other test areas on the East Coast in the United States. Right? That's interesting too. So this might sound odd, but there seems to be a logical reason and it's not Bob's sex life, but it is called the Four Bulge Collapse. I just can't stop laughing when I think about that. So as the prehistoric North American ice sheet formed during the last ice age, that thing reached as high as a mile. A mile. And it came down as far as Long Island, New York.

E: Yep. And all that debris along with it.

J: Yeah, I actually read somewhere that Long Island was made out of the debris that the shelf was pushing. I don't know how accurate that is.

S: Well, those kind of structures like Long Island and Cape Cod specifically, those are glacial geological features. Whenever you see that, you know a glacier has been there.

J: So if you picture, you visualize this frigging ice shelf that existed and all the weight that it was pushing down, it was like so hard pushing down on the landmass that it was sitting on, it actually pushes the landmass up in other areas. Right? So Ben de Jong, the lead author of the recent published study said, this is a really cool thing he said, it's a bit like sitting on one side of a water bed that's filled with very thick honey and then the other side goes up. But when you stand, the bulge comes down again. But you would think you'd have to push really hard to push that honey on the other side of the bed, but it will slowly push, right? So that's what that ice shelf was doing to the actual landmass. And now that it's gone, I mean, it's really gone now. Of course, there is still some ice mass there, but it's nothing compared to what it was. The ground is coming back down. As the ice plate, the ice mass continues to decrease and that weight decreases and the ocean levels rise, that's it. There's nothing stopping it. Now this is, of course, you could blame man-made global warming and things like that. But this thing is going to do this. This is going to take place over the next 100 years, no matter what happens.

S: I think it's going to continue happening for thousands of years too. It's not done yet.

J: Yeah, but in 100 years, the water level will have gone up. However you want it, wherever the water line is right now, it'll be up six inches more.

C: So what does that translate to? How low is DC now? How long until there's actually... How long until the mall is flooded?

J: Well, I would think that if we say in 100 years, it's going to go up six inches. I mean, I've seen simulations of what the slow creep of the rising sea level would do. And six inches is a lot more than it sounds.

C: Yeah. Especially if you're already close to sea level.

S: All right, I have to interject my little bit of pedantry, Jay.

J: What do you got?

S: You called it the Ice Age, which is a popular term, but it's actually really the last glacial period.

J: Oh, whenever. Whenever cavemen and dinosaurs coexisted, okay? You saw it on TV.

S: We're in the current Ice Age right now, which goes back about a million years.

J: A million years, yeah.

S: Two million years.

J: Two million, right, exactly.

S: Yeah, and the Ice Age has periodic glaciations. The most recent one was the one that was from 110 to 12,000 years ago.

J: Yeah.

S: Yeah.

J: That's right. Thanks.

E: Wooly mammoth time.

S: Right, exactly. And then when the glaciers melted, then there was mass extinction on the North American continent.

J: Speaking of wooly mammoths, come on. Are you telling me that early man or Neanderthals didn't ride those guys? Like, come on.

C: No, they ate them.

J: Yeah, but they had to ride them. I mean, where do you think George Lucas got the idea in Star Wars?

S: Yeah, that's true. All right, but you know what else, Jay? You know what else? It's time for Who's That Noisy.

Who's That Noisy (38:25)

- Answer to last week - longest interior echo

J: Who is that noisy? Okay, so last week I played a sound, or this was weeks ago, Steve. How far away are we going now?

S: Whatever, you bring us up to date.

J: I'm bringing you up to date. When last we had played Who's That Noisy, I played you this sound. [plays Noisy] It's going to keep going. Any guesses?

B: Is that a supernova?

J: Nope. Anybody else?

E: It started with a bang of some kind.

C: Some sort of like a firework?

S: Well, I heard last time that it had a really long tail.

J: Yeah, it did.

B: Gamma ray burst.

J: So check this out. All right, so first, the person that guessed it was Mark McDonald. Good guess, Mark.

E: He had a farm.

J: Mark actually knew exactly what it was. This is the world's longest interior echo, and it was produced in an old oil storage tank in Rossshire, Scotland. Now, these tanks were created between 1939 and 1941 to provide a huge bomb-proof reserve supply of furnace oil for the warships of the home fleet against the growing German threat. Alan Kilpatrick, an archaeologist, investigator, and Trevor Cox, who is a professor of acoustic engineering, shot a gun inside one of these giant, and when I say giant, I mean giant. It doesn't look real when you look at the picture. It looks fake. These giant storage tanks, and they echo lasted 112 seconds.

B: Can you use them for propulsion in spaceships?

J: Guys, as a quick comparison, guess how long the previous record was?

E: Four foot one.

B: 42 seconds.

E: 12 seconds.

C: Yeah, I'm going to go 12.

J: All right, Steve?

S: 13.

J: 15 seconds.

E: Damn it, Steve.

J: We went from 15 seconds to 112.

S: I price is righted you.

E: Totally. I hate that.

J: So the tanks were designed to hold 25.5 million liters of fuel and has a wall that's 45 centimeters thick. The space is about twice the length of a football field, nine meters wide and 13.5 meters high.

C: Jeez.

B: That's gargantuan.

J: Moving forward, this week's Who's That Noisy. [plays Noisy]

S: What is it about that that you want us to identify?

J: I just want you to listen to that and tell me what I'm hearing.

S: Okay.

B: Okay. All right.

J: Now, so Cara, you don't know this, but I'm about to tell you where people want to write in. They write into WTN@theskepticsguide.org.

Interview with Kevin Folta (43:15)

- https://gmoanswers.com/experts/kevin-folta

- Bizarre GMO report

- GMO Soybeans loaded with Formaldehyde

S: All right. Well, let's go on with our interview with Kevin Folta. Joining us now is Kevin Folta. Kevin, welcome back to the Skeptic's Guide.

KF: Hey, great to be here again.

S: And Kevin is a professor and chairman of the Horticultural Sciences Department at the University of Florida in Gainesville. You have your PhD in molecular biology and you're one of those guys who futzes around with plant genetics, right?

KF: Yeah, that's what we do. We try to use genomics tools to make better tasting fruit crops.

S: Right. I've sampled some of the – I guess they were the rootstocks of strawberries that you're, some of your research focuses on strawberries and those were quite delicious.

KF: Oh, that's right. Yeah, last year I sent you a whole bunch of different varieties that were not things you could buy in the store. And hopefully those are still productive for you.

S: They didn't do well over the winter, I got to be honest with you. They didn't winter well up here. We had a really, really cold winter and a lot of my plants didn't survive.

KF: Yeah, that happens. But maybe the future of genetic engineering can install some cold tolerance that can survive a winter up there.

E: That would be cool.

S: That would be nice. So, Kevin, I wanted to bring you up back on the show to talk about a very interesting story that I came across. This actually happened over – this happened mainly in 2013. But it is, in my opinion, it was like a perfect example of what is happening within the mainstream anti-GMO activist movement. Their anti-science activities really is shocking. So can you give us a summary? This was a stunning corn comparison that was published in March of 2013 on a website, Moms Across America by Zen Honeycutt. Was that group formally called Moms Against Monsanto or are those two different groups?

KF: I'm not sure. I think they are one and the same, but it certainly is Moms Across America has a very strong anti-GMO, anti-Monsanto bend. So I wouldn't doubt it.

S: So tell us what happened.

KF: Well, this is interesting because I got an email from a friend of mine that said, how do you explain this? It talked about something called the stunning corn comparison. It was allegedly a data table that was comparing GMO versus non-GMO corn and a breakdown of the relative nutrient content of both types. When you analyze the information, the bottom line that they wanted you to see was that these two things were like apples and oranges, that GMO corn was from outer space and loaded with toxic stuff like formaldehyde and glyphosate. Any kind of compound that was ever potentially construed as negative, the levels were very high. Those looked at as very positive. The levels were low or non-existent. If you looked at the data carefully, you saw that this really wasn't a test of a biological material. The numbers didn't make sense about something that would come from something alive.

S: I don't think you had to look at it that carefully to figure that out, to be honest with you. I glanced at this table and immediately, like the first line is available energy. The non-GMO corn is 340,000, whatever units they were using, and the GMO corn was 100. So that means, if I'm doing this right, that's 3,004 times as much energy in non-GMO corn than GMO corn. That's impossible. I mean, what the hell are they talking about? It's like they're not even—immediately, I think anybody with the slightest amount of scientific literacy would say, there's something not right here. This is like incompatible with a living organism.

KF: Yes. And when you go down the table, the next one, percent bricks, they say it's 1%, which bricks is a measure of soluble solids. And so corn to have 1% bricks has never happened. And as you go down the table further, you start seeing terms that don't make sense. Things like cation exchange capacity. What the heck is that in testing a biological material? And then as you begin to go through this table, you start to see terms that aren't compatible with what you would test for in a corn sample or soybean sample. And it turns out that this is really an analysis of soil. And this is a soil table that was made to analyze soil. They took some soil numbers and then substituted in their own to make it look really scary.

S: This has to be fake, right? I mean, this isn't a mistake. It's hard for me to imagine this is anything other than fraud, just a hoax, if you will.

KF: That was my first inclination was that these are just fabricated numbers. And whether or not it was moms across America that did it, these allegedly came from a company called ProfitPro in conjunction with a guy named Harold Vlieger who allegedly produced these data. And there was kind of a paper trail as to where this came from at one time. I think most of those websites are gone now. Yet the moms across America stood by these data. And when I mentioned on their website, assuming at the time that maybe they just made a mistake or that they had been fooled, they went after me big time. And they certainly were upset by the idea that somebody had called them out that they were promoting false data or fabricated data. And to this day, they stand by it as though this is legitimate.

E: Oh, wow.

S: Yeah, they really doubled down. Reading the comments to their post where they present this report, they call it a report because it's not really a study. It hasn't been published. It's not peer reviewed. So they call it a report, right? So they're not claiming it's an actual study. But the operator of the blog, Zen Honeycutt, essentially says, hey, it doesn't matter if this is real or not. Stop questioning it. This is information we're giving to parents so they could make decisions to protect their children. That was basically her position.

KF: And that's a position she maintained. And throughout this entire process, I've always reached out to her. People I know have had rather unfavorable interactions with her. Yet I've always maintained the idea that maybe she was misled and that it gave her the benefit of the doubt that someone was pulling her chain. And as somebody who was an anti-GMO activist and very much leaning that direction, this kind of favorable bias would certainly be compatible with her worldview and therefore promoted. So I did the next logical thing. I said, well, let's replicate those numbers. And so we talked a little bit about that just in conversation online. And she put me in touch with who is Dr. May Wan Ho and said, talk to them about replicating the study. The big issue was, is that when I tried to get the info, it started out great. Dr. Ho says, this is wonderful, we'll replicate this, we'll do a great job, we'll show you that this is toxic corn. And all those email exchanges are on my blog. And others were involved in the thread, such as the person who was allegedly the origin of the original table, this Harold Vlieger guy, and Don Huber, this former plant pathologist from Purdue, who claims that there's a secret organism that's killing people, livestock and plants. And he's got his own credulous set of claims. So I asked her if she would do this and they were on board. They were excited to do this. And I really was starting to think they must have just got some bad information that maybe they thought this was legit.

S: But then they pulled the plug before they did the study.

KF: Yeah, I had everybody ready to go. I was trying to source the materials. And I said, it would be great to have the lines that you looked at. Give me the, if we can have access to the same seeds or the same seed lines, same plants. We'd like to grow them in a variety of different environments. We had farmers lined up in Wisconsin, Indiana and Florida to grow the seeds. We had this all ready to roll, except for we couldn't find out from them what the materials were that they used. And as this started to get increasingly real and as we held their feet to the fire, and as I said, the only thing I'm asking is that I need you to be an author on this paper. Then all of a sudden they said, we're going a different direction.

J: What was the direction?

E: Away from you.

KF: That's right. Away from the scientist. I was just asking for evidence and asking to replicate their claim. And I was being kind about this because I didn't want to dismiss out of hand something that they may have considered to be reputable data and give them the benefit of the doubt. But when the light of day comes onto your situation and you scurry away, it's quite telling.

S: Yeah. I mean the doubt in this case about who knows what is actually quite irrelevant because their behavior is what matters. So you showed me, or I think it was in the email exchange was published on your blog, and they essentially said, well, we decided not to do this with you because you're pro-GMO. And your response was, no, I'm not pro-GMO, I'm pro-science. The science just happens to support the position that genetic modification is a safe and effective technology. And if it said otherwise, I'd believe that, whatever the science says, right? So they don't get that difference, you know. That reply makes no sense. This is how you resolve differences in science. The two opposing sides get together. They agree on a protocol that will resolve their difference. They sign off on it, and they agree to sign off on the results, and then that's it. The results are what they are. But they were unwilling to do that. They were unwilling to put their nickel down on actual evidence, which I do think speaks absolute volumes. This affair, the reason why I wanted to bring you on the show to talk about this, because this is this is a group. This is an activist group, this Moms Across America, that, among other things, is anti-GMO. And the whole exchange reveals so many things. As I said, if you look at this report, this GMO corn versus non-GMO corn, as you say, they don't mention specific cultivars or anything. It's not the actual kind of information that a scientific report would have. But if you look down these numbers, it's clear that they think that GMO crops are not even real. It's not even food. The fact that they would believe this report speaks volumes about what they think. Like I love there's one line that just says chemical content. What does that even mean? Chemical content was huge, of course, it was like 60, it's parts per million, like 60, and zero for the non-GMO, because non-GMO corn has no chemicals in it.

E: Well, Steve, the other categories, there are chlorides, formaldehyde, glyphosate, all these very scary, scary terms.

S: In red, yeah. The other thing I wanted to talk to you about was I know recently you had a very similar run in. So there's another scientist who's now claiming that his study shows that GM soybeans are loaded with evil formaldehyde. You remember this?

KF: Ah, this is so good. I love this, because this is a guy named Dr. Shiva Adhidurai, and he claims to be a systems biologist. And so systems biology, for people who don't know the discipline, it's where we take data from a variety of reports and a variety of information sources, build a computational model that integrates that information to help us make predictions about other genes or other factors that may influence or may be influenced to give us, let's say, a model of new genes or new processes that may be affected. It's a way of integrating multiple data sources to get some sort of output. And what he published in Agricultural Sciences, a rather low-impact journal, is a computer simulation that at the end says that GMO soybeans, compared to non-GMO, are loaded with formaldehyde. And, of course, decreased in glutathione, which is an antioxidant. And what was really sad about this is that he publishes this in this journal, and I'm thinking, oh, I hope this just goes away. I don't even want to deal with listening to what's going to happen here. But within days, the activist media, the websites exploded, GMO soybeans full of formaldehyde. So here's a computer prediction that makes a testable hypothesis that, if it's true, you would be able to measure the formaldehyde levels. But no one measured it. No one looked at whether the model was valid. They just went with the conclusion. And sadly, all of these rather credulous websites that are in the business to scare the hell out of parents, concern people, to scare them away from good food, are now bearing this title of full of formaldehyde in your soybeans. So I, right away, and this was on Twitter, reached out to Dr. Ayadurai through various mechanisms and said, OK, let's do the test. And we've arranged a laboratory in Minnesota that will measure the formaldehyde levels, an independent laboratory. I'm paying for this personally out of pocket. And I said, join me with this. Let's do this together. You're a co-author. And he has not responded. Today I found my first samples of soybeans with their corresponding isolines. I have more coming this week. And we will do the test to validate or to refute his model. And this is something where he should be involved. He should be so excited to have a scientist poised and ready to test his conclusion. Unfortunately, he's not doing it. And he's actually going all over the internet speaking on these various platforms, talking about the formaldehyde-laced soybeans. So he's refusing to do the test, yet he and his wife, Fran Drescher, are saying that we need new testing standards for GM crops, but just let's not test this first batch.

S: Let's not confirm my model. Let's not do any preliminary testing. Let's just run with it because it says what we want it to say.

KF: Right. And as I put in my blog, I said it's like you did a model of a computational model that predicts Munich is off the coast near Tampa. And you automatically now start planning your trip to Oktoberfest, getting in the boat and heading out that way. If you make a prediction that is totally wrong and inconsistent with everything we know about science and metabolism and plant product content, it doesn't mean that it's true. It means that you need to redo your model and it means at least you have to test your model to determine whether or not what you're claiming is true. And I've been really lucky to have these opportunities like with Zen Honeycutt, with Don Huber and his pathogen, and now with Shiva Adhiduri to be able to say, let's do the test. Because when you ask them to do the test, they run.

S: Yeah. So we often make comparisons between like the hardcore anti-GMO activists and the anti-vaccine community and their behavior is really the same. They're just making up their own science. They're making up their own propaganda. They're not interested in what is really, really true as is I think clearly demonstrated by these episodes and the fact that they're so unwilling to do that. I mean, it's absolutely irresponsible to run to the public with sensational conclusions that have not been validated, which is what Shiva is doing.

KF: Yes, and making it very visible and he's going out there and not saying, here's a hypothesis we can test. Let's do the next step. He's going out and saying, we need to change the laws and it's maybe no coincidence that this work, which if you look at the submitted and accepted date, were just a couple, it was very short time, shorter time than anything ever gets peer reviewed these days. It coincided precisely with the votes on GMO labeling, on national policy towards GMO labeling and what's going on as a dialogue in the House of Representatives and Senate. And so there's a very aggressive movement underfoot right now to introduce that modicum of question and that modicum of suspicion, just that one in a million chance that something might be wrong. To put the fear, that one possible possibility into the ears of our leaders in hoping to gain their favor for a political reason. And I think it's really wrong.

S: Yes, do you think they're just doing this to create some fear and doubt about GMOs right at the time where this is being debated in the Senate.

KF: It's to do that, and it's also to mobilize their organizations and their followings and the people who are the anti-GMO movement. Get them fired up about calling their Congress people. Get them to march with a sign. And let's ignore the science, as usual, and let's go after conflating bogus issues to try to scare parents away from transgenic food and transgenic technology. What they don't realize is that these are technologies that can have tremendous benefits for us and do have tremendous benefits. And I look at my laboratory and other laboratories in our country where we've solved problems that are important. Like citrus screening, the disease in our state, could be solved with a GMO solution. The problem is, is that this kind of fear keeps those technologies from advancing and keeps the good technology out of the people that need it the most.

S: Yeah, I agree. All right, well, Kevin, you keep up the good work. We'll keep plugging away. Hopefully, we could start to make some progress in this area.

KF: Well, thank you so much. And I will let you know if anybody steps up to the plate to actually test the science that they claim.

S: Yeah, keep us up to date on that. We'll maybe bring you back for a follow-up if you actually do this study.

KF: Oh, yeah, we're going to do it for sure. I'm going to do it fast so that we can let a little air out of this balloon and stop these activists from stealing places in our literature, using it to scare people away from food. It stops here.

S: Yeah, awesome. All right, take care, Kevin.

KF: All right, thank you.

Science or Fiction (1:02:05)

Item #1: Scientists have created the first artificial ribosome, which is able to manufacture proteins. Item #2: In an extreme case of convergent evolution, DNA analysis indicates that the East African golden jackal is actually more closely related to lions than to jackals. Item #3: Researchers have released a new variety of peanut that has a shelf life 10 times that of current varieties, with greater disease resistance and a healthier fatty acid profile.

Voice-over: It's time for Science or Fiction.

S: Each week, I come up with three science news items or facts, two real and one fake. I challenge my panel of skeptics to tell me which one is the fake. Cara, you're at 100%.

C: Yeah.

S: All right, let's see how you do this week.

C: Uh-oh.

S: Here we go. Number one, scientists have created the first artificial ribosome, which is able to manufacture proteins. Item number two, in an extreme case of convergent evolution, DNA analysis indicates that the East African golden jackal is actually more closely related to lions than to jackals. Item number three, researchers have released a new variety of peanut that has a shelf life 10 times that of current varieties with greater disease resistance and a healthier fatty acid profile. Evan, go first.

E: Scientists supposedly have created the first artificial ribosome able to manufacture proteins. Very handy. I imagine all the things you can do with that. The genetic engineering involved here is off the charts as far as I'm concerned.

S: Do you want to know what a ribosome is, Evan? It's an organelle inside cells that make proteins from RNA.

E: RNA.

S: Which comes from the DNA.

C: They're what make the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Rough.

S: Mm-hmm.

E: Now, I'll remember that for a long time. Exactly.

B: It's a biological nanomachine.

E: Well, regardless, scientists creating artificial ones, that's quite a feat of engineering, no matter how you cut it, no matter what it is. The next one, DNA analysis indicates that the East African golden jackal is actually more closely related to lions than to jackals. Oh, gosh. I know nothing about jackals.

C: Can somebody tell me what a jackal is? Is that bad that I don't know what a jackal is?

J: I'll tell you after Science or Fiction.

C: Okay. Don't tell me now. All right.

J: Don't cheat.

E: More closely related to lions, maybe. I really have no idea about that one. I'm so off the reservation. The last one, researchers have released a new variety of peanut. It has a shelf life 10 times of current varieties. Okay. Greater disease resistance, healthier fatty acid profile. Well, Bob will be pleased with this. He is the peanut butter aficionado of the group. I don't have a problem with this one. This is exactly the type of research we're doing trying to get our food to last longer and be more healthy for us so we can live nice, happy lives and spread all that goodness around the world. So it's down to the artificial ribosome or the jackal. More closely related to lions. Well, I'll say it's the jackal one as the fiction only because I really am in the dark on that one. I think regarding the artificial ribosomes, scientists have gone ahead and made that leap. Yeah, jackals I think is the fiction.

S: All righty, Bob.

B: Okay. The artificial ribosome. Yeah, that's awesome. I'm really a little shocked that they could construct something so small to manufacture proteins. I suspect that it would be very basic, being able to create very, very simple proteins. I normally probably would consider this one to be fiction, but I'm not going to. The peanut one. Yeah, whatever. I mean, sure. I mean, there's nothing there that's standing out, that's leaping out at me. But number two, convergent evolution, I see a big problem with this one that I think it's – I just hope it's not because it's unfortunately worded. Because what you're doing here is saying that convergent evolution is essentially the same as genetic propinquity, I'll say. And that is bullshit.

S: No, no. You're misinterpreting it. So let me explain it to you.

B: Please do.

S: The convergent evolution is that a big cat looked so much like a jackal that people misidentified it as a jackal. So the East African golden jackal was misidentified as a jackal. And now recent DNA analysis said, whoops, it's not a jackal. It's actually more closely related to a lion. Now you get it?

B: Shit.

C: I love how stressed out this makes everybody.

J: Mostly Bob.

E: It's not like we win $10,000, is it, Steve?

S: So the question is, did they confuse a cat for a jackal?

B: Right.

S: That's the question.

B: Oh, man. I went through a lot of damn news sites. None of this came up. I don't know what – I'll say the convergent one is bullshit anyway. I'll say it's fiction. Whatever.

S: All right. Cara?

C: The artificial ribosome seems legit. It's true. It seems small, but we have so many cool kind of nanomaterials now that I could see this happening and could really open up a lot of new avenues, I think, like medical treatments and things like that. So I'm excited about that one and I'm going to say that that one is true. For me, it's between two and three. The reason is because, as you guys said before, there's nothing going on with three. Sometimes they're deceptively simple. I know that I've read recently that researchers are working on peanuts that are low allergen, but there's nothing in this about it not causing an allergy. So that's kind of throwing me. And two is throwing me because I still don't know what the freak a jackal is. I feel like if I were more aware of my East African golden animals, I might be more comfortable with this one. But you know what? I think if they're working on a peanut that has a reduction in allergens, maybe some of these things could come along the way greater disease resistance, longer shelf life. So I'm going to go ahead and say that the peanut thing is real. The ribosome is real. I'm going to say the jackal one is not real, mostly because I don't know what a jackal is.

E: There you go.

S: And Jay.

E: That's how I got there.

J: Yeah. So just to take these quickly in order, the one about the ribosome, I see no reason to not believe it because just out of the sheer volume of testing and manipulation that scientists are doing, I think the devil is in the details on this one. And when we say created the first artificial ribosome, like what do we mean by artificial? With a moderately loose definition of artificial, yeah, I could see them taking an existing ribosome, modifying it and saying this is a new one. So I'll just say that one is science. Bouncing to the third one about the peanut. Absolutely. Of course. Yeah. There I don't know if this is a genetically modified peanut or if it's been selectively bred, but yes, we could this is the types of things that even Kevin Folta is doing to pull out properties that we want. So yes, that one is science. I really don't believe the one with the jackal mix up the way Steve described it at all. The thing is like that type of animal is not even close to a lion. They're two very different kinds of animals.

C: No fair. You know what a jackal is.

J: I do. I do know what a jackal is. Yeah. So whatever. This is, I think Steve swapped out something because the jackal has nothing to do with a lion. They don't even really look like each other.

C: So you think this is a real story, but it's a different animal.

J: They're all real based on something real.

C: Gotcha.

J: But it's not a lion. It's something else. That's it. So Steve, I know what you did here.

S: Okay. You think you do, Jay. I guess we'll take these in order. You guys all went for the second one about the jackal, but we'll start with the first one. Scientists have created the first artificial ribosome, which is able to manufacture proteins. You all think this one is science, and this one is-

B: Say it.

S: Science.

B: Yeah, baby. Tell me about it. How big is it? Is it big?

E: Is it in a plant?

S: No, it's small, like a ribosome.

B: Whoa.

S: Yeah. So they've been having trouble doing this for a while because they couldn't get it to keep together because there are two sort of subcomponents of the ribosome, and they kept falling apart every time they tried to have it make a protein from an mRNA. But they finally figured out how to stitch it together. So this is called a riboT, a new study published in the journal Nature. RiboT may be used to create functioning polymers. Polymers are proteins, basically. Well, technically, a protein is a polymer that's folded into a specific shape. Did you know that?

J: Yeah.

S: Yeah, the polymer is just a string of amino acids, and when you fold it into a protein, the protein has the functionality. In fact, they were able to keep bacteria alive with just the artificial ribosome making its protein.

B: Whoa.

C: Cool.

B: What the hell?

S: So they are pretty confident that it's actually working. Now, this could have a ton of applications. We could use this to make protein-based drugs, for example. You could get a vat of these ribosomes.

J: Cranking it out, yeah.

S: Cranking it out, yeah. So this could have industrial uses in medicine or in research that is quite promising. This would be a protein-making factory.

C: Or fuel. Yeah, lots of cool things.

S: Yeah. And also, Bob, this is like one more step on the way to synthetic biology.

B: Shit, yeah, man. Absolutely.

S: All right, let's go to number two in an extreme case of convergent evolution DNA analysis indicates that the East African golden jackal is actually more closely related to lions than to jackals.

J: Steve, can I dump my info now?

S: Yeah, go ahead.

J: All right. So I happen to know this because I have a two-and-a-half-year-old. The golden jackal is also called the reed wolf. Yes, and they're just small.

B: What the hell?

J: They're small wild dogs. So it's got to be a wolf. It's not a fucking lion. It's got to be.

S: Yeah, you're exactly right. It's a wolf.

J: I knew it.

C: So what are normal jackals? Will somebody please tell me what a jackal is?

B: Google it. Google it.

C: Oh, I can now. Okay.

J: They all look amazingly similar except some coloring and spotting and whatnot. But jackals are really cool wild dogs. They're actually really cool.

S: They're all in the family Canis. They're all in the dog family.

C: Gotcha.

S: So there are two species, the Eurasian golden jackal and the East African golden jackal. They were actually thought to be two populations of the same species.

J: I thought they were the same thing.

S: Yeah, they were the same thing. And then they did DNA analysis and like, holy crap, the East African golden jackal is actually a wolf. It's not a jackal at all. It probably separated from its common ancestor with jackals a million years ago. So they were off by a million years of evolution. That's not trivial.

J: They look like foxes, you know?

S: Yeah.

C: They do. It's a little foxy.

S: Yeah, I thought it was more foxy than jackally, than like a jackal.

C: The jackals look foxy.

S: Yeah. But if you look at the East African golden jackal, it does look like, to me, it looks like a wolf. Very pretty, though. Beautiful golden black fur. Very, very pretty animals.

J: Now, in the Lion King, Steve, weren't the jackals like the kind of evil guys?

S: Those are the hyenas.

J: Right. Those are the hyenas.

C: And I know hyenas. Why do I not know what a jackal is?

S: I don't know. There was a gap in your knowledge.

J: They look like little wolves, and they're adorable.

C: It's so weird, though, that this is just an animal that I'm unaware of. It's just like he's kind of shit on at the zoo. He's not out in front, I guess, because I do not recognize him.

S: It is amazing how little knowledge we have about the animal kingdom, just like the average person.

C: Seriously.

S: It's true, because we hear about the same animals over and over again. We have this very simplified view, this sort of Noah's Ark simplified view of the animal kingdom. Yeah, there's giraffes and elephants.

E: There's 26. One for each one letter of the alphabet.

S: Yeah, exactly. But when you start to read about any family or group of animals, you realize, oh, my God, the diversity within this group is so much more massive than how it gets simplified and distilled down. It's amazing. That's why I love reading about that.

E: Tamers, lemurs.

S: Yeah, there's so much diversity out there. Even in large mammals, you'd think we would know all the large mammals.

C: But yeah, we don't.

S: It's surprising.

C: You know, I was wearing a sweater the other day, and it's 50% yak. And I know of a yak, but I was like, I don't know if I've ever seen a yak.

S: They don't live around here.

C: What a weird thing. But even at a zoo or anything. And that's the same thing with jackals. I've totally heard the word. It's not like when you said jackal, I was like, what is this magical word you are saying? I've heard the word so many times. I literally had no idea what it was referring to.

J: Well, it's amazing how much you learn when you have kids. I mean, all I do is look at animal books and animal videos.

S: Well, yeah, I got into birding with my daughter, Julia. And then you realize, oh, my goodness. Even in your backyard, the diversity of birds you just were completely blind to is amazing. Which means that researchers have released a new variety of peanut that has a shelf life ten times that of current varieties with greater disease resistance and a healthier fatty acid profile is science. Bob, are you excited?

B: Yeah, it's all right. It's all right.

E: Oh, he's beyond. He can't even speak.

S: He's stunned. Stunned into silence.

B: I mean, what the hell?

J: He won.

B: What's the relation to peanut butter?

S: Yeah, everyone did. Swept me. Swept me. I didn't sell the jackal lion to you.

C: Wait, so when we win, does that mean you lose, Steve? No, we all, everyone wins.

J: Yes, yes.

B: Oh, he cries himself to sleep.

S: Cara, did you have fun?

C: I had fun, so I guess I'm a winner.

J: Cara, when we sweep Steve, Steve doesn't give us shit. When Steve sweeps us, he can go fuck himself. You can just hear it in his voice. He has a little bounce in his step.

C: Oh, trust me. We are from the same. We are cut of the same cloth because I am the biggest shit talker for no reason because I never win at anything, but I love shit talking when I do.

S: All right, so the Olay peanuts. These are called Olay because they're Spanish. That's not why they're called. That's not why they are Spanish. That's not why they're called Olay. They're called Olay peanuts. They are also called Spanish peanuts, but they are high in Olayic acid.

C: Oh, that makes sense.

S: Yes. Olay for Olayic acid. That's one of the types of fatty acids in peanuts. Another type is linoleic acid. Now, there's an important difference between linoleic acid and Olayic acid. Linoleic acid has more double bonds between the carbon and the hydrogen, and it is those double bonds which break down over time, which cause peanuts to taste rancid. Have you guys ever tasted rancid peanuts?

J: Terrible.

S: Hence the term rancid.

E: Disgusting.

S: Yeah, they're bad. They're bad. So that's the breakdown of the double bonds in the fatty acids. So Olayic acid has fewer double bonds. It lasts much longer. In fact, the shelf life of these Olay peanuts, they estimate will be 10 times that of the previous popular cultivar of Spanish peanuts.

C: Interesting.

B: Did you know that peanut butter lasts a long time? But you know what spoils peanut butter? It's when you get stuff in the peanut butter from the other things that you're making with your sandwich or whatever.

S: Like jelly.

B: That's the stuff that makes it nasty.

C: That's funny.

S: And it gets moldy.

B: Keep it pure. Keep it pure.

J: Cara, do you love peanut butter?

C: I actually am not a peanut butter eater.

B: Good. More for me.

C: Is that terrible? Yeah, more for you.

B: That's good.

C: I don't know. I'll eat it if it's like there, but I'm not somebody who's like, I just want a Reese's peanut butter cup.

E: Or if it's baked into something.

S: I'll take a spoon and just take a huge spoonful of creamy peanut butter and just eat it right off the spoon.

C: Yeah, I don't have that.

B: Peanut butter and chocolate is magic. Such synergy. But here's something. Here's something. I read years ago that peanut butter is essentially an American phenomenon and it's like a male phenomenon. That's like the biggest demographic for peanut butter.

C: Boys like peanut butter.

J: Bob, more of a guy thing.

C: Weird.

B: I remember reading that years ago.

E: Don't say that on Facebook. You'll get bashed.

J: Peanut butter was created to save people's lives for real.

C: What?

J: Yes, it was created. God, I can't remember the details.

B: Saved my life.

J: I think it was a priest who was trying to feed old people and they needed to give them something they didn't have to chew that had protein and had a caloric value, had nutritional value. And peanut butter was like perfect because it's actually good for you.

C: It's like Plumpy Nut. Have you heard of Plumpy Nut?

S: Didn't George Washington Carver invent peanut butter?

E: No, that's a myth.

C: That's a myth?

E: That's a myth.

J: No, but he used to grow weed.

E: He didn't invent it. He may have manufactured it, but I don't think he would do it. He wasn't the first one to do it. Yes, that was debunked by Seth MacFarlane of all people.

S: Yeah. While he may have made peanut butter, the preparation arose in other cultures independently. The Aztecs were known to have made ground peanuts. Wow.

C: Interesting.

S: That's cool.

C: I prefer an almond butter myself.

E: Oh, that's Jennifer. My wife eats almond butter.

J: It's expensive as crap though.

E: It's very expensive.

C: It is expensive, but I don't really like peanuts.

E: $15 a jar.

C: Yeah, but you can make it yourself if you have a really good blender.

J: Yeah, for $14 a jar.

S: The oleic acid is also more heart healthy, and they've cultivated this species to be more resistant to fungus and stuff that plagues peanut farming. I love roasted peanuts too.

J: Yeah, they're awesome.

E: Oh, gosh.

S: Walnuts are good. Yeah, I like walnuts. Almonds are good. I like everything in the culinary nut family. It's all good. Do you know that raw, raw almonds are poison?

E: Oh, yeah. Don't do that.

C: It also does not sound like it would taste good at all.

E: Cashews. Cashews as well.

S: Raw cashews are also poison.

B: Gesundheit.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:20:58)

"Science has taught me (Science warns me) to be careful how I adopt a view which jumps with my preconceptions, and to require stronger evidence for such belief than for one to which I was previously hostile. My business is to teach my aspirations to conform themselves to fact, not to try and make facts harmonize with my aspirations." - Thomas Huxley

S: All right. Evan, give us a quote.