SGU Episode 52

| This episode needs: time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 52 |

|---|

| July 19th 2006 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| SGU Forum |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, July 19th, 2006. This is your host, Steven Novella, the president of the New England Skeptical Society. With me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hello!

S: Evan Bernstein...

E: Good evening, everyone.

S: And back from her whirlwind tour of Europe, Rebecca Watson...

R: Hello again, everybody.

S: Rebecca is jet lagged, but still and also lost her luggage on a train to somewhere. But managed to crawl her way back for the podcast tonight.

R: I did. I put forth great amounts of energy and money just to get back here in time to do this podcast.

S: Well, we appreciate it.

E: I know that feeling.

R: As you should.

S: No, no skeptical encounters in Europe you were telling me.

R: Not really. Although we were, I went to a wedding while I was out there with Sid Rodriguez from the Skeptics and the Pub. And we did encounter an interesting couple who we were talking to them about a lot of different pseudoscience claims. And they have a lot of weird beliefs. And we kind of managed to talk them out of a few, I think, without causing too much disruption to the wedding ceremony.

S: Oh, good work.

R: It was pretty well done, I think. And mostly thanks to Sid. He's very good at the, about being very nice while completely destroying people's world views. It's inspiring.

B: That's a good talent.

R: It is.

S: Well, in the news today is Bush's first video of the new stem cell bill. I've talked about stem cell research in the United States in the past and how Bush basically was a executive order essentially banning federal funds for stem cell research except for embryonic stem cell research, except for the lines that were already existing. And it's become increasingly clear over the years that these existing lines are inadequate. The Senate, correctly, I think, although largely in response to public pressure, put together a bill essentially to override that, to approve federal funding for embryonic stem cell research with some common sense and political but meaningless restrictions. And Bush vetoed it. What you said he was going to do. I don't know, and that was just today, so at this point, I don't think there has been time yet to have another vote in the Senate to try to override the veto. I don't know if the vote exists. Any of you have heard anything about that?

E: I heard they do not have the number of votes necessary to override the veto.

B: Did you guys hear that at Bush's post veto shindig, he had a, there was apparently a lot of kids, a lot of babies and kids that they brought there that were adopted as an embryo before they were thrown out in these fertility clinics, just like to just to drive home that sea. I'm doing the right thing here. Look at these.

R: Wait, he had a post veto party?

B: Well, some sort of gathering, whatever it was.

E: A political show certainly it was.

R: Carl Rove last week said that the reason why Bush's vetoing the bill is because recent studies show that researchers have more promise from adult stem cells than from embryonic, which is just utter shit. It makes no sense. It's completely wrong.

S: It's totally wrong. I mean, embryonic stem cells are the most totipotent cells that there are. It is certainly possible that we may be able to derive stem cells from adult sources in the future that do everything we need them to do, but that's not where we are right now. Right now embryonic stem cells are the best. We just don't know where the research is going to go. That's the whole point. That's why it's called research. We don't know the answers yet. The most insane thing about this whole thing is that what we're talking about is using embryos that are going to be thrown out.

B: That's where it was down to Steve. In some quotes he was saying how these are people and their value is matchless and all this stuff. I'm thinking if these are people, why isn't he outraged that these embryos are being thrown out routinely?

E: Exactly.

B: Why isn't that outraged and why isn't he outlawed? Why does he permit it?

S: He would never get away with shutting down fertility clinics. You start telling people that they can't have children. I think that's politically untenable. They just pretend that that issue doesn't exist, basically.

E: Cherry picking.

News Items

Precious Bodily Fluids (5:00)

- www.newsmax.com/archives/ic/2006/7/18/100645.shtml?s=ic

CDC fact sheet on Fluoridation

S: There was in the newsmax.com, which is an online rag in my opinion, they published an article New Warnings About Fluoride. Basically, trying to say that there's new research that shows that the fluoride that we're getting in our drinking water is unsafe. They're quoting an article that was published in Prevention Magazine, which is another dubious publication. There's really nothing new in all this. This goes back to the Precious Bodily Fluids comment in Dr. Strangelove. It's still as crazy as when it was said in the movie. The fluoride that we're getting in the water is well below the safe limit. It's possible that we're getting more fluoride from other sources these days, so maybe we don't need to put as much in the water. You could quibble about little details like that. There is zero evidence that there is any real health risk from the fluoride that we're getting in the water. There's tons of evidence that it is very effective in fighting tooth decay. There's a small minority, but very vocal, relentless minority of people who just, for whatever reason, do not like this very concept of violating our Precious Bodily Fluids with anything foreign.

E: Here's what they have to offer. They say, these few. There are disturbing studies while not offering conclusive proof. They have linked fluoride to serious adverse health effects, including bone cancer and osteoporosis.

S: And they cite as a resource, Dr. Blaylock.

S: Who publishes a newsletter by Newsmax, too. That's an internal matter.

E: I noticed that.

S: He's a total quack. This guy is just selling his own cookie ideas. He publishes his "newsletter", the Blaylock Report, which is just his crazy ideas. He is not, this is hardly a respected source of medical information.

E: He warns the fluoride, maybe linked to retardation in children and numerous cancers. Well...

S: All nonsense.

R: So he must have drank a lot of fluoride as a child.

S: That's one of those issues that will always crop up every now and then.

World Jump Day (7:17)

- www.worldjumpday.org/

S: Tomorrow is a big day, you guys ready for tomorrow?

B: Oh, yeah.

E: Oh yes.

B: I got my jumping shoes ready to go.

S: That's right. The World's Jump Day. Did we talk about this before a year ago on our podcast?

E: We did. We brought it up last summer. I recall when we found it just trolling around the internet.

S: It's already world jump day again. I mean, the year went so fast.

E: It did. It did.

S: This is for those of you who may not have heard. Online organization basically trying to convince as many people as possible to all jump at the exact same time. The idea is that it will push the earth into a more favorable orbit and fix global warming, lengthen our days, which makes no sense and whatever cure would ails you. It's just pure internet mythology.

E: Yeah. Well, I mean, it was like a running joke that sort of part of life of its own and got adopted, I guess, by some people who tried to really figure out if there was some sort of possibility of some promise to something positive to be yielded out of everyone jumping at the same time to try to shift the orbit of the earth.

S: Does anyone really believe this?

R: No, I don't think anybody actually believes this.

S: This just a running joke, right?

R: It was started by a performance artist. It's kind of like a flash mob sort of thing. It's just a fun.

S: And the scientist is a made up character. The scientist promoting this.

E: It's just kind of interesting to see how one little thing, I guess, which was really supposed to be just a joke amongst his peers or whatever turned into a worldwide internet phenomenon unto itself.

B: Guys the physics behind it, pretty interesting. I went to MadPhysics.com, interesting website. The guy did just, what's the expression back at the napkin?

S: Back at the envelope.

B: Back at the envelope calculations. It's, some of it's pretty good. He estimated the amount of people that would, that might be jumping. And he was saying that the mass of everyone jumping would be about trillion times smaller than the mass of the earth, which is roughly equivalent to 2% of the energy released from one megaton of TNT, which is like a modern H bomb. Now surprisingly, the earth, the earth's orbit would be displaced by a little bit by all this, assuming that they're all jumping on one side and not completely cancelling each other out being all over the planet. It does actually move the earth. But unfortunately, it would move it a tiny fraction of the radius of a hydrogen atom. So I think that's pretty negligible.

E: The tsunami that hit last year had more of an effect as far as the movement of the earth than everyone on the earth could ever have by just jumping up and down.

S: Right. We're exploding all those hydrogen bombs you've exploded over the years.

B: You think that would have whacked our orbit many, many times over.

S: It's silly.

Questions and E-mails

Follow up on Neal Adams (10:11)

Dear Dr. Novella,I was absolutely floored by the interview of Neal Adams. While I would not suggest having such a guest on every episode, I do think it was a nice change of pace. I look forward to other such shows. I would almost suggest that a two part approach might be effective. Episode one would be the interview, and episode two would be an analysis of the guests arguments and thoughts.Keep up the excellent work.

–Howard Lewis Hershey, PA

Normally, I thoroughly enjoy your podcasts and they are usually excellent. The last one though, was a real disappointment. Neal Adams was such a crackpot that he wasn’t even interesting. His source of science information must have been people like Velikovsky and Von Daniken. I didn’t hear him say a single thing related to science that was correct. I don’t mind hearing alternate views or theories but Adams was just silly.On the other hand, I really liked the podcast with Steve Mirsky and the one last week with Gerald Posner was great.

–Jim Matthews, Australia

S: Let's go on to emails. We had a lot of response from last week's episode, our interview with Neil Adams. Without a doubt, we had more response to that interview, to that segment than any other interviewer segment on our podcast.

B: Even more than the 9/11 ones, Steve?

S: More than anything else by far, wasn't even close. Many, many passionate responses. We debated before having Neil Adams on. It was, obviously we had concerns about interviewing someone with Neil's beliefs. The interview was difficult. I mean, we was pleasant throughout, but it was hard for us to counter all of the nonsense that he was viewing. So we were concerned about what the response was going to be. Although I thought that it was a very interesting segment. All things considered for me. I thought it's fascinating. Skeptics have this fascination towards pseudoscience, kind of like watching a car wreck on the side of the road. And Neil Adams was like a hundred-car pile-up. But when you get to read two representative emails from different ends of the spectrum of what we received, the first comes from Howard Lewis from Hershey, Pennsylvania, and Howard writes: "Dear Dr. Novella. I was absolutely floored by the interview of Neil Adams. While I would not suggest having such a guest on every episode, I do think it was nice change of pace. I look forward to other such shows. I would almost suggest that a two-part approach might be effective. Episode one would be the interview, and episode two would be an analysis of the guests, arguments, and thoughts. Keep up the excellent work." Email number two comes from Jim Matthews in Australia. And Jim writes: "Normally, I thoroughly enjoy your podcasts, and they are usually excellent. The last one though was a real disappointment. Neil Adams was such a crackpot that he wasn't even interesting. His source of science information must have been people like Velikovsky and Vandanikin. I didn't hear him say a single thing related to science that was correct. I don't mind hearing alternative views or theories, but Adams was just silly. On the other hand, I really liked the podcast with Steve Mirsky, and the one last week with Joe Posner was great." So Jim didn't like the interview, Howard really did like it. I did do a little bit of rough statistics on all the different emails we got, and also we have many, many messages on our message boards about this. And about 85% of the people who voiced an opinion thought that the interview was a good idea. They liked the interview, although about 80% of them described listening to the interview as painful. (laughter) Even though they thought it was educational, they thought it was physically painful for them to listen to it. And 20% said that they wanted to reach through their computer screen and strangle Neil Adams during the interview.

R: So you're saying approximately 70% of our listeners are a masochist?

S: Basically. It was hard not to have a strong reaction to Neil Adams. Now for those who may not have seen that, we do have a notes page for each episode. And it does provide links and more information about each episode. For the last week's episode, Neil was pretty insistent on continuing the discussion. He was unhappy that we talked about him after he was off the interview and wanted a chance to respond to the things that we said. So it's okay, let's continue this in writing. So we've had a number of back and forths, and I'm still posting them, so go back there. There's three exchanges on there right now. So three of his responses and three of my responses, where we get to the nitty gritty of some of his actual claims. Although it's starting to deteriorate at this point, not sure how much farther they will go. I mean, seriously, his responses are starting to get more and more just flat out incoherent. I do think it is what I thought the value of it was, was just seeing how disconnected from reality a belief system can get. Someone who professes to support science thinks he's doing science, but the methods are so flawed. It's really basically cut off from any real connection to empirical evidence, and it just drifts off farther and farther away from reality until he, this guy honestly feels that he has disproved all of modern science, basically. That every working scientist believes things which are profoundly and easily demonstrated to be totally wrong. And he can see all this. Working scientists can't see. That's basically his view. It's just again, it's fascinating.

E: I think it's also necessary, I think, our audience and other people need to see exactly the kind of, forgive me, whacking this. People claim to have his knowledge in science, whereas it's clearly, clearly not. It's almost like a zoo. You go and you see the animals behind the cages, and here we are at the Neil Adams cage. Just look at this animal is coming up with them doing it. You sit back and you just kind of watch it. I just found it fascinating and entertaining, frankly. And I think most of our audience did.

S: Again, most data, though, I certainly understand that it was tough to take. We may have people like that on again, the future, I promise you, we will be few and far between. We try to make sure that there's something interesting to gain from them.

Women in Science (15:36)

How does the Bad Astronomer, et. al. intend to colonise space with manned space flight? Does this presume that all the women will be frozen embryos when the colony is founded, awaiting there first breath of life once all the heavy lifting is done? And if the spacemen have to raise the girls to maturity, wouldn’t that be kind of incestous – pedophilic when they start trying to increase the colony’s population? Yech. And too, if they’re willing to go without female companionship for that long, isn’t it safe to assume that all the travellers would be gay?Maybe I’m stupid, after all my brain has probably been fried by all my years of studying first biochemistry and now engineering. It’s got to be hard on my female brain, especially since apparently I don’t like engineering… (beware the sweeping generalization, my friend. that, more than anything, will feed the arguments of the Believers).My point here is HOW could you POSSIBLY have SERIOUSLY gone from pondering the lack of women in science faculties (by the way, they’re there, they’re just not in positions of power) to using the phrase MANNED SPACE FLIGHT? Yes, yes, fine, so everyone knows you can assume that Man, with a capital, refers to the human race, but really, when you close your eyes and say it, does it really conjure images of men _and_ women? How hard do you have to work to shove even the token woman into that picture? be honest. Do you truly think any young women listening to your podcast are going to automatically see _themselves_ as part of a ‘manned space flight’? (note that I don’t use the capital here, because it isn’t actually audible).And please don’t belittle this issue, words have a lot of power, and each one comes with a dictionary definition, and the colloquial connotations that it gathers during use. Using inclusive language makes an enormous difference.By the way, check your history or cross-cultural studies; there’s no way that in 20,30 or 40 years we’ll be worrying about getting more men into academia, because once a profession becomes dominated by women, the repect it get from society, along with its pay, perks, and power, plummet. How many ‘male nurses’ do you know?Cheers,

–Arleigh Jamieson Vancouver, B.C.

S: One more email before we go on to our interview. This one comes from Arley Jamison from Vancouver, British Columbia. This isn't regards to the discussion we had with Phil Plait, the bad astronomer. I can't read the whole thing and the whole that will be on the nose page, but it's a little bit long. It's going to cut to the chase. Arley writes: "My point here is, how could you possibly have seriously gone from pondering the lack of women in science faculties?" And then in parentheses, she writes, by the way, they're there. They're just not in positions of power. To using the phrase, manned spaceflight. Yes, yes, fine. So everyone knows you can assume that man with a capital refers to the human race, but really when you close your eyes and say it, does it really conjure images of men and women? How hard do you have to work to shove enough even the token woman into that picture, be honest? Do you truly think any woman listening to your podcast are going to automatically see themselves as part of a manned spaceflight? And please don't belittle this issue. Words have a lot of power and each one comes with a dictionary definition and the clinical connotations that it gathers during use. Using inclusive language makes an enormous difference. By the way, check your history or cross cultural studies. There's no way that in 20, 30 or 40 years, we'll be worrying about getting more men into academia because once a profession becomes dominated by women, the respected gets from society along with its pay, perks, and power plummet." Well, good alliteration. "How many male nurses do you know? Cheers, Arley."

E: Wow.

S: So Rebecca, you actually wrote a response to that?

R: Yeah, yeah, just a few things that I noted about AJ. I think she signed herself as. Well, first of all, regarding our addiction, I'm a writer and so I agree that words can be really powerful and one should always consider the colloquial use of word choice and how it might influence your message. And we use the word manned to talk about space flight and it's currently used colloquially to mean populated with humans, which is exactly how we chose to use the word. Whether that word conjures in your mind an image of male or female scientists on the spacecraft is influenced far more by your perception of what a scientist looks like than anything that's actually contained within the word itself. As for AJ's question about how many male nurses we know, I personally only know a few, but that's understandable since the percentage in that profession is I think 5 to 7%.

S: I think up to 8% or something or 9%.

R: Okay. I think that AJ might do well to read up on the history of nursing and why it's a profession that has always been dominated by women. The fact that nurses have always traditionally been women means that her point about profession is losing lust or once they're dominated by women, it doesn't really work. Nursing was never a well respected profession until we relatively recently began educating our nurses. And as an aside, if I told my friends who are nurses about her assumptions that their pay, perks, and power have plummeted, they'd get a really good laugh assuming that they weren't horribly offended. Nurses are actually more in demand than ever right now and a skilled nurse has her or his choice of workplace.

S: And their respect has actually increased dramatically in the last 20 or 30 years.

R: Yeah.

S: It's really dramatically increased.

R: Yeah, because they've become a necessary part of the medical industry.

S: And the culture of medicine has changed. I mean, it was sexist 30 or 40 years ago and it's experienced that the sexual revolution just like every other part of society has.

R: Right, because nursing used to be the job of women to comfort and care for people, but not in any real medical sense. But then as our knowledge of medicine has increased, we've come to need nurses to have that important knowledge as well. So we've educated them to actually be an integral part of the industry.

S: And I just have to disagree with the broader point too about women begin to dominate in academia and medicine, which is happening, is measurably happening, that these areas medicine and academia are going to decrease in power, perks, and pay just because they're a woman in it.

R: It's a completely absurd proposition.

S: Yeah, I don't buy that.

R: Nothing you can point to in the past that shows that is happening and using nursing as an example is just kind of absurd.

S: Officially on the Skeptics Guide, and I know all of us personally, none of us are sexist. We're all feminists, if you will. We all believe in the equality of the sexes and think that. And we stated categorically during that episode that people should have the ability to pursue their dreams, their potential without restriction, without being constrained by someone else's sense of what they should be doing. But however, I personally really think that the political correctness thing gets taken too far. Everyone knows that we're talking about when we say manned space flight. And honestly, the reason why I would say that and not say personed space flight is only because it just sounds silly.

R: Yeah, personed isin't actually a word, so.

S: I guess Arleigh would characterize this as belittling the point, but it's not belittlingly. It's a legitimate question about what the real impact of it is. Do we really need to completely rewrite the English language to erase all of our historical origins? To basically pretend like the history of Western civilization didn't exist the way it did. I don't think that we need to do that in order to achieve equality. That's the difference of opinion about that. It's not belittling.

R: I just think that there are some things that people just choose to be offended. And if you make the decision that you're going to be offended by something you will, and I think there's so much else out there that's still not equal between the sexes that we need to concentrate on fixing that focusing on silly things like certain choices of words that really don't harm anyone, I think that's counterproductive.

S: Right, so you're saying you should choose your battles a little bit better?

R: Yeah, and to be clear, we talk about how there's a difference between the sexes and how men in general have certain attributes that women don't have and vice versa. And that's never to say that specifically a woman can't excel in a certain category, above and beyond what her male counterparts might be able to do.

S: Right, it's not. It's not that it's even about individuals, it's just a statistical statement.

R: Right, we're humans, there's sexual dimorphism, and that's just what happens is just reality.

Interview with Bill Bennetta (22:34)

- Textbook League

[link needed]

Bill and his team at the Textbook League are a watch group organization on the textbook industry. They rate and recommend textbooks. Bill joins us to discuss the sorry state of science textbooks.

S: We are now being joined by Bill Benetta. Bill, welcome to the Skeptic's Guide.

BB: Thank you, I'm glad to be here.

S: Bill is the president, is that your title?

BB: That is right.

S: Of the Textbook League, they are a watchdog group on textbooks, and he's here to tell us about how awful our textbooks are. But Bill, why don't you just start by giving us a summary of what your group actually does?

BB: Well, the Textbook League is, it's not a membership organization, it is just five directors who run the organization. I do most of the work, I'll tell you, because I am also the editor of the League's publications. In fact, this is really all that the League does, is to publish a bi-monthly, or at least it's supposed to be bi-monthly bulletin, called the Textbook Letter, which is the only publication in the known universe that regularly reviews schoolbooks. We deal entirely with schoolbooks for middle school and high school. We do not touch elementary books. And that's really what we do. We don't lobby, we don't attempt to influence legislation or regulation or anything like that. We write a lot about those things, because that's where so much of the corruption lies is in the political system that surrounds schoolbooks. But we ourselves don't take part in political processes.

S: Okay, and before we talk about what we can do about the situation, let's try to describe it a little bit. So, give us, again, your summary of what you think the state of textbooks are. Obviously, you deal exclusively by the way with the United States, or do you?

BB: Yes, entirely.

S: So, the state of textbooks in the United States, and we're most interested in science textbooks, but you can give us the big picture.

BB: The general situation regarding science textbooks is no different from the general situation involving textbooks in all fields. It is a race to the bottom, in which the books simply get worse and worse and worse. And in a minute, I'll tell you what that means. It is controlled, the textbook industry, is a sort of oligopoly controlled by four companies and a handful of state agencies, especially the education agencies in Texas, California, and Florida. These are inseparable from each other. You can't imagine that there's a textbook industry consisting of companies, and then the education agencies that approve and adopt and buy the books are somehow separated from them. They aren't. They are all fused together in a single system that determines what the books say, how the books manipulate kids, and how the books will reflect what I call this race to the bottom. Lesson less information, more and more idiotic pictures and sidebars and fillers and articles that tell nothing and mean nothing, but look attractive, especially to teachers who, for practical purposes, know nothing about the subjects that they're teaching.

S: So how does that work? How are textbooks actually regulated in this country or how are the decisions made as to what textbooks schools will be using?

BB: First of all, in the United States, about 22 states are what are called adoption states. These are the states that have an adoption process at the state level by which textbooks are examined and approved and okayed for use in the state. The remaining states do not have such a process. Of the 22 adoption states, only three or four matter, and they are the ones that buy huge quantities of books. They are California, and Texas, and Florida, and maybe with a nod to North Carolina or something like that. The publishers don't care about the remaining states whether they're adoption or non-adoption. Now, we're talking about an industry that sells maybe four to four and a half billion dollars worth of stuff to education systems, both public and private, each year. This stuff consists of everything you remember from when you were a kid in school, right? But here's the catch. Only four companies produce basal textbooks. The thing that you think of when I say biology book or earth science book or a chemistry book or music book, only four companies produce those.

S: Can I ask you quickly why that is? Is there a reason why there are so few? You're also saying that there's really not any meaningful competition between these four companies.

BB: There's very meaningful competition. We will get to that, but not in the nature of the product that they sell.

S: Not for quality.

BB: The reason that there are only four is simply that during the past 20 or 30 years, the industry has been attempted to use the word afflicted by waves of consolidations, mergers, and acquisitions, and the four that are still standing are the four winners. They have absorbed dozens of little companies, often incidentally retaining those little companies' names as imprints. That is why, for example, Pearson Education publishes with the imprints, Princess Hall, which you've certainly recognized. Addison Wesley. Scott Forzman and a dozen others.

S: We got these four companies. They're basically being, which textbooks are used in schools is dealt with state by state. You're saying that the process that the states use is basically broken.

BB: Not from the state's point of view, and not from the company's point of view, which remember is the same point of view. Companies and the state agencies in a half a dozen big states are amalgamated into a single entity called the textbook industry. You must always keep your mind on that.

B: What about the non-adoption states? You seem to be focusing on the adoption states. How did the non-adoption states go about selection?

BB: They get to pick from the books that the publishers offer them, which have been tailored to the needs, requirements, demands, standards, and prejudices of the adoption states.

E: So it's a monopoly?

BB: Well, it's an oligopoly, okay? If you're in Illinois or New York or Massachusetts, you get to buy a book that was tailored to the requirements and demands of California, Florida, and Texas.

S: And how does the selection process work? Why doesn't it work for us? Texas that drives a lot of the industry, they had their adoption state. What process does Texas go through to decide what textbooks to use?

BB: The essence of the process in all of the adoption states, really, that the state, let's talk about California. It's not that much different in the other adoption states, okay? The state puts out an invitation to publishers a year or two before the state is going to run its selection process. It invites them to submit products for selection. And it sets up, it promulgates a set of standards or requirements that California demands to have honored in its textbooks.

R: Can you give a few examples of those standards?

BB: Oh my gosh, they range from the, they range from rational and I might even say good ones, such as no plugging of commercial products in school books with minor exceptions, for instance, California standards say specifically that if you want to show a picture of a Coca-Cola sign in Taipei, that's fine if what you're doing is conveying the worldwide impact of American cultural icons. Okay? I haven't agreed with that. That happens to be a pretty good standard, all right? That's a rational one. Here comes another rational one.

S: But we want to hear a really irrational one.

BB: Well, no, no, the irrationality comes later, just stand up, but bail with me, okay?

R: He's building drama, let it go.

BB: There is a, I'll ring a little bell when I'm ready, but you see, it will blend slowly. The bell will not be too loud, okay, for instance. It says this. Textbooks will reflect the most, the best and most recent scholarship. That's a pretty good standard, isn't it?

S: This sounds good.

BB: Now comes the funny part. That standard is never enforced, okay? Just tuck that in your back pocket for a minute. Now let's look at another one. It requires that history books should give multiple perspectives on historical events. That's another good one. There are certain basic facts of history where I guess you say you might say no multiple perspectives are available, but most things in history are matters of interpretations in light of evidence. And without that you don't have history. Well, you don't have that in California because the multiple perspectives requirement is steadfastly ignored too. Why is it ignored? It's ignored because the California adoption process, and this is the same as in Texas, is designed and controlled and run by the four big publishers. Nominally it looks as if the state is running this process. In actuality, no such thing is happening. The publishers would never tolerate an effort to enforce a requirement for the best and most recent scholarship.

S: What does that mean they wouldn't tolerate? What would they refuse to comply?

BB: They would take care of anybody who tried to foment enforcement of the day.

S: You gave us an example of that.

B: Would they whack them? Would they take them out?

R: Are they knocking people off?

BB: (laughs) Nothing so dramatic has it drive by shooting. I'm sorry to disappoint you.

R: No horse heads and beds.

E: Are you saying they control voting blocks of people? And politicians will get voted out of office?

BB: No.

S: What mechanism do they use to prevent the standards from being enforced?

BB: The most popular method is simply to threaten by political means. The removal or embarrassment of anybody who would try something of that sort. It's just not that blatant and bold. It's kind of like, listen buster, do you like being on the textbook committee? Fine. We like you too, but just shut up. And that's kind of the way it works. After all, why are these people on the textbook committee? They're punching their tickets and getting things on their resumes and so on and so forth.

S: So there aren't many people on these committees who are passionate and dedicated to quality content in our school's textbooks.

BB: No.

S: In your vast experience.

BB: In my experience, no. In my experience, if there are such people, they simply aren't listened to and I will give you an excellent example of this.

S: All right, let's hear it.

BB: This occurred during the history and social studies adoption six years ago, not the most recent one, but in California. California has a requirement that the books must be examined by content, subject matter, experts or content experts or whatever they're called. Well, California adopted a middle school book so outrageous, so outrageous that no one would take it seriously from doing anything. So I went to Sacramento and I went into the records of the adoption of the remaining records. Many may have been destroyed. The records certainly seemed incomplete. In some cases, the records pertaining to entire books simply didn't exist. But they're remained in the records. The report of three content specialists, all three of whom were academics in the field of history. All three of them recommended right in their opening paragraph. This book is so defective and deficient that it should not be adopted. Even the guy went on to tell the reasons, okay? The book was adopted.

S: So they ignored the advice of their experts?

BB: Yes, of course. Of course. The books are otherwise apart from the content specialist and stuff mandated by regulation. There's another set of regulations which mandate that the books be examined by what are called instruction materials, evaluation or appraisal panels. I forget the bureaucratic term for it, okay? These people, nearly all of them, turn out to be school teachers. Well asking a school teacher to evaluate a school book is a fool's errand indeed. The school teachers don't know anything. And to the extent that they think they know things, what they think they know is stuff that they've read in past school books.

S: Right, so exactly. So it just perpetuates the quality that was there before.

BB: Exactly. So let's switch our things to science now. Now I had, I sent to you people a big overload of articles with a suggestion that you read them in preparation for tonight's conversation. I don't expect that all of you read all of them.

R: Oh my gog, I just had a flash back to high school. Go on.

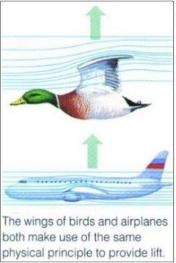

BB: So let's, let's quick into the wonderful world of science and let me cite three examples from the articles that I sent to you. Nobody in the real world believes that the way birds fly is to stick their wings out and be born along by the Bernoulli effect. I have no idea as to where this came from. I have no idea how it first got into school books, but it's in every middle school life science book now and in many high school biology books as well. It is sheer nonsense. What is interesting here is that it has been exposed again and again even in educational circles. In the physics teacher, a professional, aeronautical engineer published a wonderful article debunking this Bernoulli nonsense. Doesn't make any difference. It's still in the books.

S: That's the thing that's hard for me to wrap my mind over when I read these examples and I know that one from decades. I mean, that's been debunked. Why won't they change it? What is the inertia? What is keeping them from just correcting a glaring mistake in their own textbook?

BB: Let me give you two more examples and then I'll give you the answer to that question.

S: All right.

BB: Another article that I sent to you guys dealt with Darwin and Lamarck. Did you read that one?

S: Oh, yeah. That's a story I'd read before. Gould debunked that in one of his books.

BB: Yeah, that one I can remember my own high school biology in, let's say, if I graduated in '56, I guess I took biology in '53 or something like that. They told us that ridiculous story about, oh, Lamarck got it all wrong. He had this idea about the inheritance of acquired characteristics and blah, blah, blah. Then this was counterposed or contrasted with what Darwin allegedly said. Well, what they don't tell you is, first, Darwin believed in the inheritance of acquired characteristics just as Lamarck did. And that the distinction between them, because there certainly was one, incidentally, Darwin wrote a, I mean, I think the second or third edition of the Origin, wrote a paragraph of praise about Lamarck. So so much for the idea that these guys were either intellectually disjunct from one another or were hostile to one another. No such thing was ever true. But it makes a great story, a great, simple, minded story which teachers love.

S: But the real story is better.

BB: Yes, to you and me, to you and me, but it requires some thought. It requires some thought and some explication. So we tell him this Lamarck story over and over and over again. We tell him the Bernoulli story over and over.

S: And just for our listening audience, just very quickly, Lamarck's real interest was that the mechanism of evolution was an intrinsic force towards perfection.

BB: Yes, yes.

S: And in fact, he actually recanted that later in life by his own observations during his career. He realized that most change was local adaptation to the environment. So we actually sort of won himself over to a more of a view that was more compatible with Darwin, even though we didn't make the leap of natural selection as the mechanism. So that's a much more interesting story in my opinion.

BB: Of course it is. And how birds fly is really interesting. I mean, just think of it. They beat their wings up and down. Something which incidentally must be omitted from the books because it's completely incompatible with this Bernoulli effect nonsense. You read these books and you have the impression that birds get around by gliding everywhere. Why would a bird have to beat its wings? Well, birds really do beat their wings because they're taking advantage of Newton's third law. If you drive air downward, you get an upward force on your wings. This is too much for most teachers. They can't grasp it that way. They like the Bernoulli thing. They read it 45, 50 years ago when I read it. They're comfortable with it. They want that in their book and they don't want to see any new, fangled nonsense about beat your wings and Newton's third law.

E: So you're saying the teachers go back to these four companies and tell them what they want to see in the book and that's what the company is putting the books?

BB: That is part of it. That is part of how these books are developed. The more important part of the process is this. The companies know which books were successful last time out. Five or six years ago when the last major revisions of middle school life science or high school biology books were done, the companies know who came out best. They get these reports from the field. Their field salesman says, I went to the XYZ district and they're not buying our book. They are buying Mr. Holts book instead. Well, they get Mr. Holts book and look at what's in there and copy it. These books are produced chiefly by teams of plagiarists who are copying books from the last round which were copied from books from the preceding round which were copied from books from the preceding round.

S: There's even published data that proves that. That proves the plagiarism. You can actually even follow the lines of plagiarism through textbooks.

BB: Oh yes. Yes.

S: So Bill, you were going to tell us a third science claim that is being perpetuated in textbooks. And I hope you'll forgive me if I stick to the realm of life science or biology. And it's this. It is the organization of books around the ancient or at least old idea of the nature's ladder. The books are organized so that in surveying the living world they start with things which are kind of lowly and disgusting and inept. The stumble bumps of the living world. And then they go up the ladder and look things get bigger and better and more complex and they're more wonderful and finally you get up to the mammals who are sitting on the top rung of this ladder. You have to kind of imagine this as a circus act. On the top rung of the ladder are the mammals and they are balancing on their shoulders, man, the best organism of them all. Teachers love this stuff. When you see the kinds of rubbish and distortions that have to be analyzed and outright lies, that have to be printed in books to sustain the idea of nature's ladder and man as the emperor of the universe and so on. Some of this stuff makes your hair curl. One of my favorites is telling kids. For some reason this always comes up with fishes. We are always carefully told that here's how fishes reproduce. The male squirts some stuff and the female squirts some eggs. But pretty much the fertilization is ineffective and a lot of eggs go unfertilized and the whole process is ineffective, wasteful and crummy. Well, what's the truth? The truth is that in fishes that use external fertilization, fertilization rates are typically 100 percent. Maybe down to 98 percent, if the fish is having a bad day. (laughter) This is all clear from the literature. Now can you name an organism that is terribly inefficient in its use of eggs and spramata zones? Can you name an organism in which the females produce far, far, far more eggs than ever get fertilized?

S: Well, humans.

BB: Yeah, you're talking to one.

S: But they have to maintain this myth that mankind is the most efficient and best.

BB: That's right, that's right. So we're terrific. I even saw a book once that now mankind is the best organism of all. Mammals are pretty good, you know? After all, that's the group to which mankind belongs. Birds are even worthy of some respect because they are "warm-blooded" the way we are. That makes them, well, if nothing else, it makes them cuddly and fuzzy and nice as opposed to those cold, naughty things that you pull out of ponds. So, in any case, they ring the changes on heart chambers. Two chambered heart and fish, three chambered heart and amphibians, four chambered heart and birds and mammals. And that just shows you how things become better and more complex as you go up this imaginary winner. They never tell you that as you go up the imaginary ladder, you also find an entire system is not only being reduced in complexity, but maybe even dropping away entirely. That's the third example I wanted to cite.

S: So, okay. So, so far what you're telling us is that the textbook quality suffers because the companies rely heavily on plagiarism, on perpetuating simplistic mythologies, and on catering to the desire for this sort of simplistic icons in science. But you also sent us articles that talked about what seems to be a separate source for dreadful gaps in textbooks. And that is political correctness or multiculturalism. So, give us some examples about that or tell us about that.

BB: Now you've got to, you've got to the other great determinant of textbook content. And it bears directly on all of this adoption stuff. Because what the, what the school book companies do is try to anticipate what will fly in terms of political correctness and to make their texts correct so that no one will challenge them on the grounds that the books may actually convey some truth. Like for instance, that the modern world has been shaped in the past 500 years by something that was invented, invented during the Renaissance or somewhat before that by a bunch of white guys. It's called science. And that's why our world has changed more in the past 500 years than in all of the accumulated millennia before then. Well, gee, that's kind of rough and tough. And the kids are going to, kids are going to shrink down behind their desk and cry if they don't happen to be white guys. And so you better keep that out of the books any instead to make up these fairy tales about scientific discoveries that never happened but which can be ascribed to Berbers and Hottentots and Eskimos or whatever other bunch you want, just to make it clear that nobody ever did anything better than anybody else. This incidentally is the motivation behind the effort in a lot of books to deny that anybody ever discovered anything. This brings from the Columbus deal, right? Who discovered the New World? Well, correct answer is interesting. Columbus and Vespucci. Well, it's not politically correct to admit this now that Columbus discovered the New World and you should see the hand springs and double talk that these books go through to pretend that, well, he really didn't discover anything. And of course, they don't mention Vespucci because interestingly, since the old cliches about Columbus discovering America didn't mention Vespucci, it's not necessary to refute and denigrate the idea that half of the discovery of the New World was attributable to Vespucci who figured out what it was. But the best thing is nobody should really discover anything because that way everybody's equal and it goes and from there, it just gets worse.

S: So give us an example in your experience of like the worst distortion of the history of science or whatever that you came across in this mode.

BB: Oh, let's see. I think I sent you an article of our school losing our science. At some point, it becomes unavoidable to acknowledge that somebody thought of something. So what you have is Pierre Curie has been abolished from history and everything that the Curie's did together is now ascribed to Marie Curie alone. There, the rad framers love that, okay. They dug up one Glencoe, but Glencoe is a manufacturer or publisher of School Book of Division of McGroyo. I loved it. They dug up some black guy who was the draftsman who made the drawings to accompany Alexander Graham Bell's patent application, okay. They didn't tell anything about Alexander Graham Bell or their telephone just about this black guy who was the draftsman. And now you want to double whammy. One book, I think it was a physical science book devoted a whole page to a black woman artist. They neglected to show any of our artwork. The important thing was to show her face so you could, there. Now when some black radical group is going through the school book and counting up how many black faiths, good, they get a point for a black face, okay. Why a black woman painter was in a science book to begin with was never explained, but nothing has ever explained. And if you think that I was joking when I talked about counting things up and giving points, I wasn't joking at all.

S: So that's exactly what they do. They just flip through the book and see that there's a balance.

BB: That's exactly right.

S: Maybe a million different races just to make sure it's all works out even.

BB: Everybody has to be equally represented and never mind that they had nothing to do with anything that we're talking about, all right. I remember a book, the chapter was about ecology in a phony middle school book. They dragged out George Washington Carver and made him into an ecologist while pointedly ignoring Latka and Volterra and Darwin and all of the other people who really did found the science of ecology. But they got themselves, and there was a picture of George Washington. So they got a mention and a picture credit, okay. But the best of this, the best of all this rubbish is recounted in a book that I think everyone who hears this broadcast should read. It's called The Language Police, How Pressure Groups Restrict What Students Learn. Written by the historian Diane Ravich, I think it came out in 2003, but a nice little paperback edition was put out in 2004 by vintage books. I am unabashedly plugging it.

R: Now Diane Ravich, that's a woman, right? Okay, just putting that out there so we get a point. Go on.

BB: Put that in your table, all right. Good. What she tells is when editors at a company called Holt, Holt Reinhart in Winston, and editors, they were working on an elementary school reading series. These characters went through a particular book, not the whole series. In this case, we're dealing with just one of the books. And they made sure that there were equal representations in both mentionings and authorship of selections and pictures of both males and females. And the guy, the Holt guy wrote in his memo, there are 146 of each exactly. This count does not, however, include animal characters. You know, you're rabbit, that kind of thing. Now you think that's funny or pathetic or both, so do I. But when the book came up for adoption, the Red Femme Crazies did the counting and did count animal characters and found out that males predominated, okay. And the streaking was heard all over the state of Texas because they were convinced that little girls would be damaged if there were too many, if there was a preponderance of male animals in the reading book. And I forget what the outcome was, whether the book was rejected or whether old tore it all apart to put in more Sally rabbits and Jennifer rabbits or something like that. But this is what it's down to. And this is the other great role that textbook adoption plays in these adoption states is that the books are put up as targets for every crazed pressure group that you can imagine.

S: There's no truth lobby there, right? There's no one saying this book doesn't have enough accurate facts in it.

BB: That's right, that's exactly right. Who would be in the truth lobby? Well, I guess we're in the truth lobby a little bit, although we don't lobby, we try to expose what's going on, but the point is everybody who has an axe to grind is free to grind it and this affects the books before publication. It's when the editors are going through and saying, now do we have enough earth-shaking scientific discoveries by Eskimos? All right [inaudible]. And at the same time, they take out all of the white males that they can possibly get rid of. All right, I recently reviewed a middle school science book which pretended that nobody knows who invented, who built the first heavier than air flying machines. They were simply called two inventors.

S: Just two inventors, no names.

BB: Right, no Wright brothers, no brothers. My god, if you call them brothers, I guess that would count as two points against you, right? Two males? All right, hell with those Wright brothers, they're out of there.

S: It is sad, clearly there's no problem with making sure that important contributions by women and minorities are being fairly represented. There's no, I wouldn't even have a problem with them saying, putting the history of science in context during this time society and therefore science was very male-dominated. And it's how it looked like it was. And you can even say that the contributions of this woman was all the more amazing because of how she was prejudiced against in her time. And wonderful it is that it's not that way now or at least it's much better.

R: The biggest problem with this extremism is that it's going to cause a bigger backlash against making sure that women and minorities are represented for what they do accomplish.

S: You just can't have affirmative action for the truth. You can't rewrite history because it's inconvenient. And I do think a lot of this comes from the postmodernism crowd who basically believes that there is no truth. It's all just a narrative and you could tell whatever narrative you want. You might as well make it fit your social desires and since there is no objective truth, it doesn't matter if you completely rewrite and make up stuff.

BB: Well, there's a little more to it than that because at least when we look at public education in this country. The public education establishment has actively embraced social manipulation as the primary purpose of so-called public education. Quite apart from the fact that the information that it purports to convey about how birds fly is completely wrong. Quite apart from the fact that it says that uranium is a synthetic element, that aspirin is a polymer and that aluminum is a liquid at room temperature. This gives you an idea of the kind of people who write the books or a day they know nothing about what they're writing about.

S: Bill, we're running out of time. Before we go, I just want to address one more topic. I think we're certainly convinced and outraged at the low quality of our textbooks and I'm almost afraid to ask the question, but is there anything actually practical that anybody can do about this?

BB: No. No.

R: That was depressing.

S: So if I'm a parent, and I have children in the public school system and I notice that their textbooks are outrageously poor in quality, I have no recourse as a parent?

BB: Let's think this through, who could possibly form a constituency for reform in these cases? The state governments, not at all. They're in the business of catering to pressure groups and of seeing their own weird devices of social manipulation incorporated into the schoolbooks. The publishers, publishers don't care at all. Publishers haven't the slightest interest in what they say except to the extent that it makes the books saleable. The education community, very few of them know anything, fewer of them care. The degradation, especially of science education in this country has been going on for not decades, but a couple of generations. Who's left? Parents, we get emails all the time from parents. Parents who are outraged at the books that their kids have been handed in school. But what do you think about that if you're a parent? Think about this. The school isn't going to listen to you. You go up there and you say, and you say, that's not how birds fly. Well, nobody wants to listen to you because they have bought the book. They have made the commitment and now they have a stake in defending their choice and in never admitting that the book is a pile of garbage. Now we're going to go to the newspapers. School's going to take that out on your kid. But there's a far more important point. At the end of this year, your kid is going to emerge from that biology class. Ignorant of biology, but one way or another, it's over. Now what's your motivation? Where is the constituency for change? There really is none that is identifiable and potent. The race to the bottom will continue for this reason. The books will get worse and worse. They will say less and less. They will make less and less sense. They will be more and more overloaded with the kind of splashy pictures and idiotic human interest tales that dumb teachers like. They certainly will go on telling kids that aspirin is a polymer and that birds fly by holding their wings out and letting Bernoulli carry them along.

S: So on that happy note, I think we're going to have to end it. Bill, it was a pleasure. Thanks for coming on the skeptics guide.

B: Thank you very much.

S: We enjoyed talking with you.

R: Thank you.

BB: I hope you got good and irritating.

S: We came in irritated. I think we left you outraged and bewildered.

R: And just a little depressed.

S: Thanks again. You take care, Bill.

BB: It's been a pleasure. Bye-bye.

E: Thank you, Bill.

S: Well, Bill from the Textbook League certainly had a lot to say. I suspect this is not the first time he's spoken on this topic. Very informative, very passionate.

R: A little depressing, but yeah, very interesting.

E: Think about what he has to do. He's got for years now, for decades. He's been stacking up these textbooks and having to read the same old and gets worse every year. Yeah, I get the sense that Bill is getting a little jaded and cynical after doing this for a number of years. He's probably right. It's just, it's hard for me to accept that there's nothing that we could do about it because you just want to say, well, we have to be able to do something, the lobby or form of the action group or something but it's hard to accept defeat, I guess, until you've exhausted all of your options.

R: Well, people should definitely check out his website though. There's a lot of really great stuff on there. It's very interesting.

E: It's sobering. Very sobering.

B: I think his organization should become lobbyists. Somebody's got to do it.

S: Yeah, but he seems to think there's no, there's the political will isn't there. There's no constituency. There's no way to maintain it. I don't know. I have to think about it. But we have enough time for science or fiction and our skeptical puzzles. Let's go on to science or fiction.

Science or Fiction (1:07:12)

Theme: Small things

Item #1: Researchers have discovered a bacteria that can extract gold from dirt.[1]

Item #2: Material scientists have developed a nanofilm that can form tubes 100,000 times stronger than carbon nanotubes.[2]

Item #3: Researchers have developed a technique to use microbes to make electricity directly from corn husks.[3]

| Answer | Item |

|---|---|

| Fiction | Nanofilm |

| Science | Gold from dirt |

| Science | Electricity from corn husks |

| Host | Result |

|---|---|

| Steve | win |

| Rogue | Guess |

|---|---|

Evan | Electricity from corn husks |

Rebecca | Electricity from corn husks |

Bob | Nanofilm |

Voice-over: It's time for Science or Fiction.

S: Every week I come up with three science news items or facts. Two are genuine. One is fictitious and I challenge my skeptics to figure out which one is fake. This week we have a theme. The theme is small things. Ready?

R: Yes. I love small things.

S: Good. Item number one. Researchers have discovered a bacteria that can extract gold from dirt. Item number two, material scientists have developed a nanofilm that can form tubes 100,000 times stronger than carbon nanotubes. Item number three. Researchers have developed a technique to use microbes to make electricity directly from corn husks. Evan, why don't you start?

Evan's Response

E: I think one or three are fiction. I think two is sound. And I'm going to guess. Really doing a coin flip here. I guess the number three is fiction.

S: Number three is fiction. Alrighty. Rebecca?

Rebecca's Response

R: I'm actually kind of thinking the same. I've been gone for a few weeks and so I have no idea. I haven't read anything about any of these.

S: You're flying blind for one time.

R: Normally I've read up almost this stuff. But yeah, this time I have to kind of take a stab at it. I agree. The corn husks, saying just sounds a little off.

S: All righty. Bob?

Bob's Response

B: Bacteria getting gold from dirt, I'm going to say that's true. Microbes, getting electricity from corn husks, husks, not, this is sound very plausible to me. So I kind of agree with you guys on that part. But number two, nanofilm tubes, 100,000 times stronger than nanotubes? You know, that's just, to me, that's such an outrageous claim. I'd like to think that that's way out of whack. If it's true, wow, that's great. And I'll be happy to be wrong, but I'd just say two is definitely wrong.

Steve Explains Item #1

S: Everyone agrees that bacteria can extract gold from dirt. And that is in fact true, that is science.

B: Yeah, I've read that one.

S: You've read that one? So apparently the bacteria gobble up little gold molecules and coat themselves with it as some kind of defense against toxins. They actually, interestingly, didn't know this until I read the article that they, there was some suspicion that this might be the case because like in the vicinity of gold or deposits there are little nuggets of gold and they can exist in these little clusters that kind of can kind of look like a colony of bacteria. So someone said, hmm, I wonder if you know bacteria is actually forming those little gold nuggets and they have discovered bacteria that in fact do that. Obviously, the gold is already there in the dirt. They're just sort of collecting it into little nuggets by their metabolism. So that one is true.

B: Aren't bacteria awesome?

S: They are.

B: I just love bacteria.

R: Sometimes.

E: But viruses are great too.

S: No, all viruses suck.

B: Bacteria are awesome.

E: Hey Steve, before you go on, I want to know if I can call the Monti Hall rule into effect right now? Change my answer from number three to number two. Now that you've revealed that there's a goat behind door number one.

R: I like goats.

B: On that note.

S: Let's see. Bob thinks that the nanofilm tubes are fiction. And both Rebecca and Evan think that the corn husks are a fictional. But Bob thought that one was kind of fishy too. So let's talk about that one first.

Steve Explains Item 3#

S: That one is science.

E: See, I should have changed my answer.

S: I want you to think about it actually that's not that amazing because basically any cellulose based material, that's energy, and you can extract energy from it. You can either make it into ethanol or you can burn it directly. So basically what these microbes do is they eat desalulose. They also, I think they mush it up and they mix it with solid waste or with some kind of organic waste. And then they can, with the microbes, they actually make a little circuit out of it and they can actually directly produce electricity from that.

B: How efficient are they, Steve, do you think desalulose is the article mentioned that?

S: It does. The electrical production is about one watt for every square meter of surface area at about 0.5 volts. So that's not a lot for a square meter. So you need to have a vast amount of this stuff. But basically with this process though, it would oxidize everything that there is to be oxidized in the corn waste. So which is good. Most, about 90% of the, and they call it the stover. I didn't know that either. The corn stover, I guess, that's what's left after you take all the good stuff out. Most of that is like 90% of that is just left in the field to rot. And that's actually a lot of energy. A lot of solulose that we could extract energy from one way or the other by either making it into ethanol. And you know, there's some questions about whether or not that is energy efficient or not. Well, this way we can actually just directly produce electricity from it or hydrogen.

Steve Explains Item 2#

S: Which means that number two, that material scientists have developed a nanofilm that can form tubes 100,000 times stronger than carbon nanotubes is fiction. Bob is correct. I mean I tried to come up with a figure that would be big enough that it would be fair. 100,000 times stronger than carbon nanotubes is pretty amazing.

B: That's too strong.

S: Unfortunately, it's fiction. But what is true, what is true, that this is based on actual report Bob, that they have developed a nanofilm that does spontaneously roll into tubes. One side expands the other side shrinks and it can roll into tubes. And you can control that process so that you not only form tubes, but you can form all kinds of three-dimensional shapes. The potential application of this is self-assembling stuff, right, at the nanolabeling.

B: Absolutely, that's great.

S: You start with this film and you, whatever, through the application of a current or something, some forces you actually coax it into spontaneously folding up to form complex three-dimensional machines, nanomachines, or circuit boards, or transistors, or whatever.

B: The other important issue is can they control the size of these things? If this is a way to control the size, that's one of the stumbling blocks for the nanotubes is to create uniform sizes instead of a huge variety of different sizes. That would be a breakthrough as well.

S: So nanotechnology marches on.

B: Absolutely.

Skeptical Puzzle (1:14:22)

Last Week's puzzle:

When is a boomerang a type of dinnerware?

Answer: If the dinnerware is a saucer - when Kenneth Arnold reported the first modern UFO's sighting he described them as boomerang shaped but described their movement as skipping like a saucer. The term flying saucer was coined, and from that point forward the saucer shape has become the standard icon for alien spacecraft.

New Puzzle:

If you are floating in a boat on a pond, and you are holding a 20lb cannon ball - if you drop the cannon ball overboard into the pond will the level of the pond rise, fall, or stay the same?

(Contributed by listener John Maddox)

S: Let's give you the answer to the skeptical puzzle from last week. The puzzle, if you recall, was when is a boomerang, a type of dinnerware? And I suggested this is a play on words and there is a skeptical angle to it. I got a few emails and there was a few guesses on the board about what the answer might be, but nobody got the right answer. This one was a bit more challenging. But what if I told you that the dinnerware is a saucer? Would that jog any memories?

R: No.

S: OK. You remember Kenneth Arnold?

E: Sure.

S: Reported allegedly the first modern UFO sighting. Yeah, he reported seeing a number of UFOs and he said that they were shaped like boomerangs, but that they were skipping across the air of the clouds like a saucer. That led to the reporter describing them as flying saucers, coining the phrase flying saucer. And since that time, the shape of UFOs has often and typically or iconically been described as saucer shape. But what Kenneth Arnold described, he said their shape was a boomerang. They moved like a saucer. So that's when a boomerang could be like a saucer.

R: Steve.

B: Wow, Steve.

R: That was a stretch.

S: It was a puzzle.

R: That was a tough one.

B: That was a one tough puzzle.

S: Well, the last one was easy. I had to give a tough one for balance.

B: All fans in the spectrum.

S: So let me give you a new puzzle, which we'll give the institute next week. This one comes by a listener, John Maddox. So he gets full credit for this one. Now, John was the first one to actually take us up on our request to, if you have any interesting items for science or fiction or puzzles to send them into me, we definitely want to get as many people cooperating in this as possible. So you know of any great puzzle send them in. Unfortunately, John, when he actually sent in was a set of three items for science or fiction, but he sent it to everybody. So you guys got this too. So I couldn't use it as a science or fiction.

E: I was hoping you weren't catch that.

S: So thanks, John, but you got to read the small print. On the website where we solicit you to send in suggestions for science or fiction. It says to send it directly to me and not to everybody. So if you're going to do that in the future, send it to snovella@theness.com, just to me alone. But this is one of the things that John sent in. It's just a logic puzzle. If you are floating in a boat on a pond and you are holding a pound cannonball, if you then drop the cannonball overboard into the pond, will the level of the pond rise, fall or stay the same? So this one's a multiple choice. It should be easier, just a pure logic puzzle. So that is all the time we have for this week. Evan, Bob, Rebecca. Thanks again for joining me.

R: Thank you, Steve.

E: Thank you doctor.

B: Good episode.

S: Rebecca, it was nice to have you back. You were missed.

R: Thank you. It's good to be back.

S: I'm sure all of you, all of your numerous fans missed you, so I'm sure they're glad to have you back as well.

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by the New England Skeptical Society. For information on this and other podcasts, please visit our website at www.theskepticsguide.org. Please send us your questions, suggestions, and other feedback; you can use the "Contact Us" page on our website, or you can send us an email to info@theskepticsguide.org. 'Theorem' is produced by Kineto and is used with permission.

References

|