SGU Episode 465

| This episode needs: transcription, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 465 |

|---|

| June 7th 2014 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

G: Gwen Pearson |

| Quote of the Week |

Don't let us forget that the causes of human actions are usually immeasurably more complex and varied than our subsequent explanations of them. And these can rarely be distinctly defined. The best course for the story-teller at times is to confine himself to a simple narrative of events. |

From 'The Idiot' by Fyodor Dostoevsky |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

This Day in Skepticism ()

- June 7, 1753: the British Museum is founded. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_museum

News Items

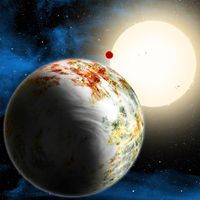

Mega-Earth ()

Secondary Drowning ()

Medical Information on Wikipedia ()

Lady Hurricanes ()

Black Hole Magnetism ()

Who's That Noisy ()

- Answer to last week: Fox

Questions and Emails ()

Question #1: Third-Hand Smoke ()

I read that there are studies that suggest that third-hand smoke is hazardous to infants. Is this something to be concerned about, or is it too early to tell?Thanks!- Blake CaldwellPennsylvania

Interview with Bug Girl (47:08)

S: Joining us now is Gwen Pearson, better known as Bug Girl. Bug, welcome to The Skeptic's Guide.

G: Hey! It's good to be back!

S: Yes, welcome back, I should say. So, we asked you to come on the show to get caught up on a couple of things. We really, really, really want to know how those bees are doing. We've been worried about them!

E: Yeah.

R: You know those bees. You know the ones.

S: Bees.

G: Yeah, so ...

E: They hang out with the birds.

G: w hich of the twenty thousand species of bees do you mean?

J: The ones that were dying. You know, the ones that were on the internet?

(Laughter)

R: The ones that are gonna destroy the world when they're all dead.

S: The honey bees?

G: Honey bees! Oh! Okay. So, that species, right? (Laughs) 'Cause, yeah, that actually is a really good illustration of an issue that I think a lot of people miss, is that there really are twenty thousand species of bees in the world. And we tend to focus on just one, which is our domesticated one, the honey bee. The one that we keep in little barns, and steal all their food.

There's all of these other bees; and it turns out that the more we research native bee species that are not honey bees, the more we find out they're actually the ones that are doing all the work! And the honey bees are just bastards that are taking all the credit for it.

S: Those damn honey bees!

B: Oh wow!

S: Screw them!

J: So, really? A lot of the other species are doing a lot of the pollen collection, and honey-making?

G: Yeah! Not honey-making though. Not honey-making. But they are doing the pollination. And so, for a lot ...

B: That's good news.

G: of plants, when you actually look at the numbers, it turns out that almost all of the pollination is being done by native bees. It's kind of like, we think of the honey bees as the big, important singer. Oh, let's call them Beyoncé, for example.

E: I get it.

J: Are you going somewhere with this?

G: Stick with me!

J: Because don't bring up

R: I'm pretty sure Destibee's

J: Kanye West. I don't want to hear about the bee that represents Kanye West.

G: No.

R: Destibee's ...

G: Well, he's a drone. So he's gonna die after ... never mind. You don't want to know. I realize where I was gonna have to go with that, in terms of the bee reproductive cycle. We don't want to go there. So, anyway, we have our lead singer, which is the queen bee. And she gets all the press. But you also have to have the backup band. And the native bees are the backup band. If you don't have both pieces, nothing works. There's also a lot of evidence that the native bees are in bigger trouble than the honey bees.

B: Aa!

G: Yeah. Because they have very specific requirements about places where they live, and things that they need to eat. And they don't have somebody who is keeping track of them, and building them houses, and helping them out. It's actually a much more complex problem than just “the bees” are dying.

Having said that, and then really ignoring, in terms of the honey bees, actually, they're doing okay. I just really want to kind of bang my head on the table a lot actually, when I read the media coverage. They're not gonna go extinct. They're fine.

S: Good to hear that.

G: There are many bee keepers that are losing a lot of money, and that are losing bees. The reason for that though, is really varied. So, what do you think the number one killer of bees is in the US?

S: Fungus.

J: Pollution.

B: Aliens!

R: Bug zappers.

S: GMO.

E: Yeah, right? Round up.

G: (Laughs) Okay, none of you got it. So, it's varroa mites. And it's a parasitic mite that is actually pretty big. If you look at a picture of it on a bee, it would be kind of the equivalent of us having parasitic chihuahua. And they basically climb into ...

B: Wow!

G: Yeah, I know! They're huge! You can see them walking around on the bees. Yeah, it is really gnarly. These things are the leading killer worldwide of honey bees. And they're very difficult to treat, because they get into the hive. And what they do is they actually crawl in to the baby bees' cells. And so they start by basically feeding on the baby bees, the larvae. And then when the bee hatches out, they just ride along with her. And the bee transports them wherever they need to go, so they can infest new places. Essentially, the mites are just kind of riding around. The bees are like their sexual taxis, I guess.

S: The pimpmobiles

G: But more than anything else, they're food. The bees are food.

E: Oh yeah.

S: They're well stocked pimp-mobiles.

G: Yes.

J: So, Bug, can't we create something to kill those parasites?

S: You need to create a toxic chemical that will kill the parasite.

G: Pesticides that do some of the worst damage to bees are pesticides that we put on the bees on purpose to kill the mites.

S: Ah.

R: Darn it.

G: Then somebody mentioned fungus. And we also put pesticides on to kill the fungus, that kills the bees. There's a lot of things. It's not that there is a specific thing that is killing bees. It's everything wants to kill the bees. I could list a thousand different things that will kill your bees.

S: Is it just because we raise so many bees in a small space, that we're just creating an environment where stuff is going to evolve to eat them?

G: That is a part of it, I think. And there's a lot of new work going into the genetic composition of honey bees. Because there is a lot of uniformity. But, having said that, in general, the nice thing about having bees, and having bees be linked to humanity for so many years, is we can go back in time, and look at really detailed records. And so, you can see all of these diseases going way back in time for the honey bees, anyway. Things like foulbrood, which is exactly what it sounds like. (Laughs)

S: Foul brood.

G: Foul Brood, yeah. Oh, it's nasty.

S: So, Bug, part of the reason we got you on the show tonight also, is because I read somewhere on the internet that some honey bees are making this blue honey that will give you autism.

G: What!

S: I may have made up the bit about the autism.

G: Okay. Well, that would not surprise me that somebody said that though, sadly.

S: But there is this magical blue honey out there.

G: Yeah!

S: So, how does that happen?

G: That's actually not uncommon. Bees like sugar. And actually, in the winter, there is just yesterday. So I'm on a couple of bee listervrs, where bee keepers discuss ... in the winter, when it's a really tough winter, the bees will have to eat more. And they'll eat up all of their stored food. And so, bee keepers will typically feed them extra food to keep them going through the winter. And that can be sugar syrup.

But what they had discovered was that you can get fondant, the stuff you make the really fancy cakes out of.

B: Yeah!

G: That's cheaper to feed your bees. And the bees really like it.

R: At least somebody does.

G: Yeah (Laughs). Yes, give it to your bees. So, yeah, if it's sweet, they will go, and they will seek it out, and they will eat it. And they will turn it into honey, and take it back to the hive. And so there's been a whole bunch of different cases of bees eating things that are funkily colored. But the common theme is always it's something really sweet. And it's usually candy that, the one that you were talking about, blue honey was, I think, an M&M flavoring. I've seen it green; I've seen it orange; it's basically when you leave sweet stuff out.

Actually, if you leave a jar of honey sitting out over a nice, warm afternoon. There will be bees in it. And the bees will take the honey.

R: How ironic.

B: It's called recycling.

R: We already have honey, stupid bees.

(Gwen laughs)

J: But wait, wait, wait. If they take the honey, do they digest it, and do whatever they do to turn it into their honey? Or they'll just keep it, and not change it.

G: They will go ahead and take it in, and process it a little bit. But the process of making honey is actually pretty amazing. Honey itself is a supersaturated sugar solution. And it gets that way, essentially, the common way of describing honey is bee vomit. And it's sort of, a better way to put it would be, maybe, specially processed bee vomit. (Laughs)

B: Wow.

J: So, they'll digest the honey that they find, and they'll kind of re-honeyize it.

G: Part of what they're doing is they are evaporating water out of the nectar and the honey. If you find some plant nectar, and sip it up, it's really very dilute. So what they're doing is concentrating it, and making that supersaturated solution. And they do that by essentially sort of hoarking up a little bubble of water and nectar, and then drying the water out, so that it becomes very concentrated. That's why if you have honey, and you let your honey sit for a while, it will eventually crystallize.

J: Honey bees will actually make honey, and then they'll eat it later, right?

G: Yes.

J: So it is them just saving food.

G: Yes.

R: So, when it comes to blue honey, some people apparently are using that as proof that since the dye can transfer from what they're eating to their honey, that that also means that insecticides and GMO's or whatever magical poisons they come up with, are also able to be transferred from whatever the bees are eating into honey. And that makes honey dangerous. What do you think of that?

G: Well, there is such a thing as dangerous honey. There are several plants that when bees feed on it, the plants themselves have toxins. And the bees will concentrate those toxins.

E: Naturally occurring toxins?

G: Yeah.

(Bob laughs)

G: Poison has to first of all, has to be in the nectar. That doesn't happen with a lot of the compounds that we're talking about. Things like GMO's (sighs) the problem with GMO's, and for that matter pesticides, is it's really not about science at all. It's about peoples' fears of the unknown, and fear of not being in control. and fear of things that are new.

I can show you many, many, many research papers. And there are many. Honestly, the AAAS put out a position statement[1] – which is pretty rare, actually – basically saying GMO is perfectly fine; get over it. (Laughs)

Okay, they didn't put that in, but that was the subtext, in my mind. So, there's plenty of evidence that very clearly says, “No, it's fine, as long as it's used appropriately.” But the people who are getting upset are not interested in evidence. And I wish I had an answer for that, because, and it's a conversation I have a lot about bees, because I have the same conversation about pesticides and GMO. There is no evidence right now that GMO plants are harming bees.

R: Yeah. So, just to be perfectly clear, when it comes to pesticides, the pesticides may be on plants, but they're not in the nectar that bees are slurping up, and so it doesn't actually get into their system; it doesn't get into their honey?

G: It depends on the pesticide, because we have this huge range of chemicals that we use in agriculture. The issue there though, is what's the dose for a bee? What's a toxic dose for a bee? And then, what's a toxic dose for a person, to have an effect? For both of those questions, there doesn't seem to be any toxic dose for a person, if it's a whole person. You can do things to individual cells that are in culture that are a little worrying, but that doesn't really come up a lot.

It's almost always, again, using a really high concentration that you wouldn't encounter. There is a lot of press the last month about this study[2] that came out of Harvard, and it was terrible! It was absolutely terrible. The problem was, because it was done at Harvard, it got a lot of press. But what they didn't tell you was, it was done at Harvard by a man who is not an entomologist, who is not a toxicologist, who doesn't really seem to know a whole lot about bees.

But by golly! He is convinced that he is gonna prove ... Some of the experiments he's done, I have used them to demonstrate to students, “Don't do this.” When you're not having an effect, after a month of your experiment, the way to fix that is not to double the dose of what you're feeding your bees in pesticides. Because you're not getting what you expected, so you're just gonna ramp everything up until you get the results that you wanted. That's not how science works. (Laughs)

S: Yeah, eventually you'll get to a toxic dose, if you just keep going up and up.

G: Oh, yeah! And also controls are kind of important; I'm just sayin'. So, but the thing is, there's all of these different things happening. So, first of all, we're in a culture where there's a lot of suspicion. A lot of people are very suspicious of corporations, and what are corporations doing, and scientists, what are scientists doing?

We really focus on one particular thing. So, GMO's are bad. All these sorts of stories; there's always a villain. It's very cause-effect. One thing is causing this other thing, because those make good stories! We're all about stories, because that's what people do, is they tell stories. But the problem is that's not how the natural works. The natural world is super-complex and really difficult to study. And there's a million things all tied together, and it's really hard to parse them apart. That does not play on CNN well at all.

S: It's almost as if biology is a complex system.

G: Yeah!

E: Wait a minute, wait a moment...

S: All right. Well, Bug Girl, we appreciate you straightening us out about the bees and the blue honey.

(Gwen laughs)

S: It's been weighing heavily on my mind.

E: Next time.

S: I'll bring the birds, you bring the bees, all right?

R: Aw, you guys make a good team.

S: All right, well, thanks a lot, Bug Girl.

G: Okay!

R: Thanks Bug!

(Commercial 1:02:16 – 1:04:20)

Science or Fiction ()

Item #1: The commercial strawberry is octoploid, meaning it has four entire genomes (four complete sets of chromosomes) in each nucleus. Item #2: One of the first strawberry scientists was a teenager that examined strawberry plants and arranged them by genetic complexity into a “geneology”, 100 years before Mendel, that still holds up to today’s molecular resolution. Item #3: Today’s commercial strawberries descend from a cross between two species; a wild strawberry brought to France from Chile by a spy in 1714, and an ornamental plant called the meadowsweet, brought to France from N. America in the 1500’s. Item #4: Strawberries are in the same subfamily and are closely related to roses. They are also in the same family with apples, plums, and almonds.

Skeptical Quote of the Week ()

'Don't let us forget that the causes of human actions are usually immeasurably more complex and varied than our subsequent explanations of them. And these can rarely be distinctly defined. The best course for the story-teller at times is to confine himself to a simple narrative of events.'This is from 'The Idiot' by Fyodor Dostoevsky

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

Today I Learned ...

Honey bees can make honey in different colors (like blue) depending on what they are fed.

References

|