SGU Episode 434

| This episode needs: transcription, proofreading, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 434 |

|---|

| November 9th 2013 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guests |

C: Chris Mooney |

| Quote of the Week |

If we go back to the beginnings of things, we shall always find that ignorance and fear created the gods; that imagination, rapture and deception embellished them; that weakness worships them; that custom spares them; and that tyranny favors them to profit from the blindness of men. |

Baron d'Holbach, German philosopher |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

This Day in Skepticism

Florence Rena Sabin (0:30)

R: It's a really good day for birthdays.

S: Yeah!

E: Ooh!

R: You know that? November 9th? Big science birthday day.

E: Cool

R: Let me tell you about a couple. Starting with the ones you've never heard of.

(Evan laughs)

R: Number one: Florence Rena Sabin was born November 9th, 1871. And she was the first woman to hold a full professorship at Johns Hopkin's School of Medicine.

S: Thank you for pronouncing the name correctly.

E: What, the woman's name, or the university?

R: Yeah

S: Nine out of ten people say John Hopkins.

R: Oh, no!

B: Oh god no!

S: Instead of Johns Hopkins.

R: There are at least three Johns at Johns Hopkins, so, you do have to pronounce ...

S: Johns Hopkins, thank you.

E: Johns Hopkins.

R: She was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and the first woman to head a department at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. She investigated the lymphatic system, and was one of the people who proved that it developed from the veins in the embryo, and grew out into tissues, which was apparently the opposite of what was thought at the time. So she was an awesome pioneer for women in medicine. Florence Rena Sabin.

S: Yeah, she was pretty bad ass.

E: Very cool.

B: Happy birthday, Florence!

E: Yeah!

Banjamin Banaker (1:42)

Carl Sagan (2:04)

News Items

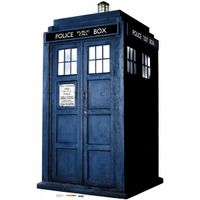

Tardis Science ()

Moving Stones ()

Blushing in the Dark ()

Rock-Paper-Scissors Robot ()

Who's That Noisy ()

- Answer to last week: The McGurk Effect

Swindler's List: Kevin Trudeau ()

Questions and Emails ()

Question #1: Li-Fi ()

On podcast #433 you referenced Li – Fi and stated that line of sight was necessary . On Podcast The Science Show-full program dated 10/18/2013 Mr. Haas explained why line of sight was not necessary. I assume that you in your usual fashion, researched Li-Fi. Could you please send me links to sources that would refute Mr. Haas as to line of sight.I have been listening to your podcasts for many years and find them to be delightful, informative and your cast of ”the usual suspects” amusing and brilliant. I am seventy five years old and have no scientific training but my curiosity for science is insatiable.Thanks to the wonders of Apple and a DryCase® I am able to listen to you while swimming my mile at the YMCA three times a week.If you send me a mailing address and payee, I will send you a small check to support your podcast (and slightly assuage my guilt). I won’t every use pay pal.Keep up the good workGaylen Rebbe Simi Valley , Calif

Interview with Chris Mooney and Indre Viskontas (41:08)

S: Joining us now are Chris Mooney and Indre Viskontas. Chris and Indre, welcome to The Skeptic's Guide.

I: Thanks for having us.

C: Yeah, great to be here.

S: Now, Chris, you are an author and a journalist. You have authored four books, correct? Including, The Republican War on Science

C: Yup. That's me.

S: And Indre, you are a neuroscientist and an opera singer.

I: Yep! That's me.

(Laughter)

B: Wow.

S: Good. I got that straight. I was making sure I didn't – Chris wasn't the opera singer.

E: Opera man.

C: On Hallowe'en maybe.

S: I understand that you guys have a new science podcast that you want to talk about.

C: Oh yes! We have Inquiring Minds; and this is a project of the Climate Desk, and I also work there. The Climate Desk is a consortium of outlets that cover climate change. That includes Mother Jones, Grist, The Atlantic, Slate, The Guardian, Wired. And the show is not just climate change; but every fourth or fifth show will be focused on environment probably. But it lets us sort of really explore the space where science, politics, and society collide; including, but not limited to, environmental science.

S: So you're not afraid on the show to take political issues head on?

C: Heck, no! We just did a big, pretty popular psychology of politics show with Jonathan Haidt, who basically writes about how liberals and conservatives are driven by different core emotional impulses that they're not necessarily consciously aware of. So, yeah, we took it right on.

I: Chris and I have different interests, and so we highlight those on the show. So my interests are more science-related with an emphasis on neuroscience, but also, anything to do with medicine and biology. And Chris tackles more of the political and climate-based shows.

C: Yeah, but I make you talk about them.

I: You do, often nonsensically. Yeah, we have a slightly different format than we did in the past. So now, Chris and I start out with a kind of ten minute segment about news from the headlines related to science; and then we go into a long-form interview, which is our signature style.

C: And then we talk about the interview, but not that long.

I: We try to stay succinct, but sometimes we don't always manage that.

S: But this isn't the first podcast you two have done together.

I: No, we used to co-host Point of Inquiry, that was run by the Center for Inquiry; and I came on board on to that podcast almost two years ago now. And I was there for about a year and a half. Chris, you were there for a couple years.

C: Yeah, three I think.

S: But you still do the interview solo, but you sort of chat with each other before and after the interview.

C: Yeah.

I: Yeah, it's pretty hard, often, to schedule guests in such a way that all three of us would be available. Also, each of us has an interest in different guests. So we take the lead on a particular interview.

C: So there will probably come a time – sorry – there will probably come a time when we both – especially if it's a live event, where we co-interview some one – but for the most part, that's not what we do.

R: Speaking from experience, it's very difficult to group interview people.

J: I know, right?

E: What're you talking about?

(Laughter)

C: How do you know?

R: Yeah, yeah. Lots of experience.

S: Well call it "gang interview."

I: You guys seem...

R: So, what kind of guests are you guys having on?

I: Well, we just did a live taping at the Bay Area Science Festival with Alison Gopnik, who's a child psychology researcher. She talks about how babies are smarter than adults, or smarter than we think at least. So that was kind of fun. But we've had everyone – we started out with a couple of pioneering frontiers women. So, Sylvia Earle, the oceanographer and Marsha Ivins the former astronaut. Then we had Nobel-Prize winner Randy Schekman on the week that he won the Nobel Prize,

J: Nice!

B: Wow!

I: which was kind of exciting. I was interviewing him, and his phone kept ringing. And he kept having to pick it up and put it down. It was very kind of him to stay on the interview, but it was the first time in an interview where I actually didn't mind the phone ringing.

B: Yeah, right.

I: It added to the excitement.

C: Appropriate. Yeah, we've done a couple shows that are in my bailiwick. I already told you about one, it's on the psychology of politics, which I think is endlessly fascinating and important. And I did a science of science-communication show where I actually had two researchers who were on the cutting edge of figuring out how to make people actually wake up and believe in science.

R: I think, was that the one ... was Dan Kahan on that one?

C: Yeah.

R: We talked about him recently.[Link needed]

C: Oh really? I had some one who disagrees with him.

R: Yeah.

C: I had them both. And honestly, at the end of it, I'm like, "I don't know who's right." That's...

E: That's pretty good!

S: So, how do you communicate science? What's your philosophy?

C: The debate was, it was climate. But you could see how it would apply to other issues. In fact we did bring up how this would apply to evolution. One researcher, Stephan Lewandowsky has experimental evidence that telling people that there's a strong scientific consensus actually works. In other words, telling people ninety-seven percent of scientists believe something, most people just don't want to be going against ninety-seven percent of scientists.

But Kahan has shown that actually, people are really ideological, then they're more than happy to – or at least they will reinterpret the claim, and say, "Oh, there's not really ninety-seven percent." So they were actually then on that basis, basically debating what the approach is.

The opposite approach, if you don't want to just tell people about the ninety-seven percent, is gonna be framing. It's gonna be figuring out what the value system of the audience is, and trying to, in essence, repackage to talk about the issue in a way that doesn't provoke resistance.

S: Yeah, what I find interesting about all of that is that it comes down ultimately to psychological manipulation. You're just trying to exploit some aspect of human psychology in order to get people to listen. There was just a study for example looking at physicians convincing parents to vaccinate their children. And the technique that seemed to work was when the physicians assumed the parents were going to vaccinate their children, and just talked as if they had already decided to do so, rather than saying, "Do you want to vaccinate your children." Again, it's just, "okay, I believe it. That works, because it's psychological manipulation. You're just using social pressure of one type or another to get people to go along.

I: They must have read Richard Wiseman's latest book, The As-If Principle.

S: Yeah.

I: And were just acting on it.

S: As if.

C: But how could it be otherwise, really. Yes, it's true. Yes, when you tell scientists about the wonders of framing, some of them bristle and say, "Aren't you talking about spinning?" But, in effect, how could you not be, if you're persuading some one, how could you not be in some way appealing to their psychology.

I guess you could just completely, clinically lay out information, and not even have it in an order, to try to not manipulate. But the effect would just be that no one would be interested.

B: It's just a tool of effective communication. That's all it is.

S: Yeah, but not only are they not interested in it. It just flat out doesn't work. Physicians have been doing this for decades now. And this has, the public service announcement. “This is your brain on drugs”, right? Let's give people information, and they'll make rational decisions! And shock! That doesn't work! You have to psychologically manipulate people into making rational decisions.

R: But then, yeah, as Chris' point goes to show with that interview, the problem becomes ...

S: How?

R: what does the science, yeah. What does the science tell us about how to actually go about that, because it does seem like every week there's a new study coming out that conflicts with the previous one.

C: Yeah, this is fast-moving. Also, this is a science that's not exactly physics, right? So, it's both of those things. So it turns out that there's not a best way. Plus it varies with the audience. So you have to also study the audience. And you will have different best techniques depending on the audience. So it's still an art in many ways.

S: Yeah, that sounds right.

C: So nobody can explain scientifically why, well, actually, maybe a little bit. But nobody can explain scientifically why Neil Tyson is so good at what he does, except that he's just incredibly electric, which is probably partly a personality thing. But there's something to the art of communication that I think will always be there to...

E: There's more than one way to skin a cat often too. You mentioned Neil deGrasse Tyson, and his approach. But at the same time, Carl Sagan, who I wouldn't call electrifying presenter by any stretch, he still had a mannerism all himself. It really kind of drew you into every word he was saying. He captivated people in a much different way.

I: Then you have Stephen Hawking who speaks through a machine, and is extremely charismatic because he's so intelligent, and what he says is so fascinating.

R: Good point.

J: It is amazing that his personality can come through there; and to me it shows that there's something more than body language and all that. There is something to be said about the way people put words together. What words do they line up, and how does that feel? You can get a feel of something, but from reading a book, and there isn't any body language with that.

S: So, of course obviously, we agree with the basic notion that you want to make science communication entertaining. At least we aspire to that. But where do you draw the line? For example, I was reading your article on Mother Jones, Why Most of What You've Heard About Cancer is Wrong. which is a provocative headline. The article's fine, but that's the kind of headline that I would scoff at as sensationalizing or hyping, you know what I'm saying? So what do you feel about that.

C: Well, I don't know. Let me – I'm sorry to answer a question with a question – but you said the article was fine. So, most people reacting to that one on Twitter and elsewhere – and that article really got around – they actually were surprised to read what was in the article.

S: Well, I wasn't surprised by any of the facts in the article because I knew them already because I'm a physician. But they're presented in a way, you're taking some basic fact of science and trying to present it in a way that makes it sound really exciting; although some of them are things like eating fruits and vegetables are actually not gonna protect you from cancer. That one's interesting because it's a very common misconception. But the facts just don't bear it out. That's the kind of thing we would talk about on the show.

Another one, hey, dinosaurs got cancer. Okay, that's all right. I'm not sure why that's especially interesting; of course they got cancer! Every animal gets cancer.

C: I don't think most people know that though.

B: Sharks don't!

SG: I think there are people out there who believe that sharks don't get cancer, which is not true. In fact, they do. There's also people out there who think that cancer is something that is a product of the industrialized world. So why would dinosaurs, who are living in the natural idyllic Eden that we've destroyed with industry get cancer?

So that was the impetus behind that particular fact. That was my interview, and I wrote a lot of it along with Chris. Both of us have different styles in terms of writing. And I came around to this notion that you really want to bring people in, and then tell them the facts as they are. So we didn't, as you hopefully noticed, we didn't say anything incorrect. We fact-checked very carefully. We didn't sensationalize within the article.

But we still need to grab peoples' attention. There's so much media out there. People have so little time to spend reading stuff. So, if a headline can grab your attention, then we can fill your brain with knowledge. I think we've done our job.

C: Yeah, we actually – the podcasts run as articles, as you've seen. And the articles are usually pretty long. I'm actually – this is a journalistic enterprise. So they're fact-checked, et cetera. So we're pretty careful.

SG: Yes. And there was one that we left out, which was really about how people have this notion that if you smoke a pack a day for fifty years, you're going to get lung cancer. But in fact, the numbers don't bear that out. Yes, you're way more likely to get lung cancer than if you didn't smoke a pack a day for fifty years. But your likelihood is still on the order of one in eight, or thirteen percent depending on how long you've smoked, and whether you quit, et cetera, et cetera.

So the vast majority of people aren't gonna die from lung cancer, even if they've smoked a pack a day. We decided not to include that ultimately in the article because we felt that there would be a lot of confusion; that people would say, “Oh, are they trying to say that smoking doesn't cause cancer?”

But that was one of the choices that we had to make. But at the same time, I still feel that getting people to understand these kinds of misconceptions about cancer is actually really important.

S: Yeah, but you raise a very important issue; something that we've talked about amongst ourselves on the show; and that is when you're confronting misconceptions or myths, you can very easily inadvertently promote them. Or, no matter how you try to clarify something, there's always a deeper level on which somebody could misunderstand or misinterpret what you said.

SG: You're right. That's how memory works, right? In the end, you bring your cognitive biases to the way that you read something. And even if you change your mind in the moment, then when you remember it three, four, five days later, you misremember it as a fact as opposed to a myth. That's one of the reasons we didn't include the lung cancer point, which I was sad to see...

C: We didn't want – smoking can also get you in a lot of ways other than lung cancer.

SG: Sure, it's still bad for you. We don't want, you know...

S: But that's something else that we confront all the time, is like you're talking about if you were going to talk about the, “Not everybody who smokes gets lung cancer,” you have to then also include all the caveats, all the possible ways in which people will misinterpret or misunderstand that point. Then it just gets endless!

So we encounter that every week, where we know, there's only so many side issues and caveats that we can explore, and we just wait for the emails to come rolling in to explain to us all the things we didn't cover. And that's just the background noise of doing the podcast. Do you guys find that too?

SG: Yeah, that was why we cut out the lung cancer thing, because we started adding, “Okay, but it's got stroke, and hypertension, and all these other issues, plus all the other cancers that are involved. And the article just got too long. So we had to make that …

R: It's too bad, because it is a really interesting fact, which I did not know.

SG: Yeah! It's fascinating.

C: When you see that happening, I think this is why one of the things that we cover, will cover, will continue to cover, is the psychology of how people interact with science. When you see that happening, you know it's happening, Steve, because of a motivation, right? And you know you've hit somebody in a particular place emotionally by some stance that you've taken, and then they proceed to argue. This is how it works.

Then when they proceed to argue, they proceed to seize upon whatever is good for arguing. So it might be, “You left this out.” Interestingly, this is why often when you get as a journalist, some one says, “This was incorrect! You need to run a correction.” Usually, it's actually, you look at the claim, it's actually, no, that's an opinion. (Laughs) But they think you're wrong, but actually, no, they didn't even assert that you were wrong! They actually just sort of said, “I disagree.” But it was so emotional that they had to say, “You're wrong!”

SG: It's great that these things are complicated, right? Because that means there's gonna be work for us for decades yet. Things aren't gonna get solved tomorrow.

S: Oh, it's endless. Yeah, absolutely. I also think that's why, part of the reason why we explore these issues in the context of skepticism, which is sort of the meta-knowledge about thinking, and information, and knowledge, and science; trying to get people to think about their motivations, their logic, the way they're framing their discussion. What's an opinion versus a fact?

Then we can appeal to them on that level when they do things like raise their opinion as if it is a fact. Or, like, we just got an email from somebody who is saying that the ninety-seven percent of scientists who think that global warming is real, they're the ones who are biased, because they need to keep their funding rolling in, you know? And the three percent who disagree with them, those are the people who were unbiased. That was how he dealt with the ninety-seven percent issue.

SG: Yeah, we've heard of that a lot. And in fact, a lot of people have questioned that particular number, even to me on Facebook and elsewhere. It's interesting how people have a real issue with that particular number.

C: Oh yeah, that one threatens a belief system. It goes straight at – and this is why – I don't mean to circle back too much – but that's why it's so … it's a debate whether that's good communication tactic.

S: Right.

C: Because it goes straight at the heart of what some people think is true. It should be confrontational. And the question is does confrontational work? It was amazing as research is suggesting that it just might! Because a lot of people that are overwhelmed by the fact that there's such agreement, that they don't feel they can counter it.

S: Yeah, it is funny. Sometimes there are those times when people knuckle under the evidence. And I'm almost surprised when it happens. But it does happen regularly. Or they're not aware of all the misinformation, and the fact that their head is filled with things that are just simply not true. When you overwhelm them with actual facts, they go, “Oh, wow! There must be something there.” Of course, somebody could overwhelm them with misinformation, and the same thing happens.

SG: I think that's one of the big reasons why the 9/11 conspiracy theories - especially Building Seven – have continued to proliferate. There are these manifestos of quote-unquote “evidence,” suggesting that the Building Seven was deliberately taken down by the government. That to me is fascinating that people find that so compelling.

R: Yeah, we were actually just talking about that a couple of shows ago [link needed] because it was still coming up. We were still getting many emails about it from people who found it completely convincing. They had seen some Loose Change type video online and just bought into it entirely.

C: It's special because it's one of the few, well documented completely left-wing falsehoods, where you can actually show that it is predominately left wing. There's a couple of other ones, but a lot of them are falling on the right. That's one that is clearly not. It does correlate with ideology. It does swing left.

R: Do you think that if a Democrat had been in office on 9/11, do you think that today, 9/11 Truthers would be predominately Republican?

C: Yeah, I think that's, or it would be something else, right? Because you can't tell what people are gonna actually get fixated on. But yeah, absolutely. There's no doubt that there's a much stronger – I think there's a study on this. I'd have to dig it up. There's much stronger inclination to believe in conspiracy theories about the President you hate.

R: Yeah.

C: That's actually pretty bipartisan. But I think that the 9/11 Truthers, one of the left wing irrationalities that is the most stark.

S: Yeah. I would have previously said that GMO and Monsanto is another one, but the data doesn't necessarily bear that out.

C: Yeah, it's more complicated...

S: It's more complicated because I think the libertarian or the anti-government right may also be buying into that as well.

C: Nuclear is one.

SG: Yeah, I was wondering, to what extent are the Truthers libertarian versus liberal?

C: I don't think they are. I'd have to go look, but I am pretty sure that it was an anti-Bush liberal kind of thing, and still is.

S: Yeah, but there definitely is also a subculture of conspiracy theorists that are sort of equal opportunity conspiracy theorists, right? They don't swing right or left; they just believe in any conspiracy.

C: Right. That's Lewandowsky who was on the show with Kahan, who has done research on that and the consensus message. He and others have shown that conspiracy beliefs correlate. So there's this independent factor, as he calls it, the conspiratorial belief that's separate from the ideology.

SG: Yeah, just like religiosity is to some extent genetic, right, in the sense that it doesn't matter what you believe, but it matters how fervently you believe that's coded in your genes. They look at these twins studies that show twins separated for their lifetime, if they're super-religious, they might believe in different religions, but they are equally fervent. So maybe this conspiracy factor is some how related to that.

C: We're so doing a show on this by the way. I don't know who the guest is, but I don't think it even matters, ultimately. The genetics of religion, I think it's just gotta be done.

S: The God gene, right? We gotta find the God gene?

(Laughter)

C: Yeah, but it's not one gene though.

S: Yeah, of course.

C: It's the identical twins research which just keeps showing again and again.

S: Well, Chris and Indre, I'm already enjoying your new show. Good luck with everything.

C: Thank you so much for having us.

SG: Thanks so much!

S: Yep, a lot of fun having you guys on.

(Commercial 1:02:45 – 1:04:18)

Science or Fiction (1:04:18)

Item #1: A new long term study of astronauts finds that prolonged exposure to microgravity may reverse atherosclerotic changes in blood vessels. Item #2: Researchers have found that playing rock or pop music increases the efficiency of one type of solar cell by 40%. Item #3: Orthopedic surgeons have identified a previously unknown ligament in the human knee.

Skeptical Quote of the Week ()

“If we go back to the beginnings of things, we shall always find that ignorance and fear created the gods; that imagination, rapture and deception embellished them; that weakness worships them; that custom spares them; and that tyranny favors them in order to profit from the blindness of men.”– Baron d’Holbach

Announcements ()

- Announcements: Phoenix Area Skeptics Society Special appearance by Steven Novella Friday November 22.

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

Today I Learned...

Sharks do get cancer, despite rumors to the contrary.

References

|