SGU Episode 870

| This episode is in the middle of being transcribed by Hearmepurr (talk) as of 2022-04-30. To help avoid duplication, please do not transcribe this episode while this message is displayed. |

Template:Editing required (w/links) You can use this outline to help structure the transcription. Click "Edit" above to begin.

| SGU Episode 870 |

|---|

| March 12th 2022 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

| Guest |

BW: Brian Wecht, American theoretical physicist |

| Quote of the Week |

Our Richie? The world’s smartest man? God help us! |

Richard Feynman's mom |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Tuesday, March 8th, 2022, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and we have a special guest rogue this week Brian Wecht. Brian, welcome back to the SGU man.

BW: Hi, I'm happy to be here.

S: Evan is literally busy doing some Ukrainian man's taxes. He wrote his email saying my friend like this whole horrible situation about somebody who has to go to Ukraine to get their family out or whatever and like he has to do his taxes tonight before he leaves for Ukraine.

BW: Oh poor guy.

S: Yeah so Evan's like I can't not do this I have to miss the recording yeah and we're not flexible unfortunately this week, this is the only night we can record. So no Evan, but we got Brian. Brian's visiting us in Connecticut.

BW: I'm live from Steve's basement.

C: Really?

BW: Yeah, yep.

C: Oh, awesome.

BW: Yep.

S: Not that you could tell, we're all just in front of computers. But yeah he's physically here and he was visiting because we were we're testing our new fully live version of the boomer versus zoomer game show that he's helping us develop.

C: Oh fun.

BW: Yeah it was, the set, so Jay and Ian constructed this set and it looks, it just looks so great. I'm staring at it right now, and it really is like when, when this thing, the first time we're gonna do it live is that the the no-show on, what's the day, is it April 23rd?

S: April 23rd.

BW: Right. In Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. And it's gonna be so much fun to have this thing actually go live. We've done it online a few times but this is like definitely a level up from from that.

S: Yeah it's a lot of fun, you know, the bit the core of the show is we pit the four generations against each other. Boomers, gen z, millennials and zoomers. We have different categories of questions. And the questions are kind of balanced so there are some questions that you know the older generation should have a little bit of an edge on and then there's other questions that the young kids will definitely have an edge, on you know what I mean? So it's like who knows more about the other person's generation. It's a lot of fun and yeah we've play tested it several times and the winners have pretty much spanned across the age range, so I think we're you know, George is mostly writing the questions, I think he's doing a great job of sourcing them, you know.

BW: The last couple times it's been the zoomer because yeah we're trying to make sure it's not just trivia, but there's also like other you know kind of mental challenge brain games kind of stuff so it is accessible to really anybody.

Ukraine Invasion Updates (2:45)

S: So we talked about Russia's invasion of Ukraine last week and there's a couple of updates because you know, we're talking mainly off the cuff but yeah we're trying to keep up to date as best as we can on the news. It's hard because obviously we you know, we don't have any special access to inside information,we're just basing what we're saying on the you know public mainstream media basically. A lot of people have asked us like, how does somebody follow an event like this? How do you get access to reliable information? How do you know what's reliable? We don't know, we don't have any inside track, so that we use the usual method which is basically be skeptical of everything. If something sounds weird you know double, triple, quadruple check it. Try to use as many different sources as possible and see if there's, how reliable they are, and are they all sort of pointing in the same direction. But again that doesn't totally answer your question for you because sometimes all of the media is telling the same narrative even though the narrative is bullshit.

C: Well especially when the media's state run.

S: Yeah well, yeah but we're not even talking about like Russian media, just like US media, like how does our US media know what's going on. So you know you want to just listen for clues just like is this speculation, are there, where are they getting this information, you know, how solid. Tis is like an official report from. Is there a video showing the person saying the thing. Like you know, just as much objective information as you can. And then of course the internet is a wash with it, good and bad, right. So there's people on like in the streets where the war is happening showing videos. And yet, and there's also things being shared going viral on social media that are that are misinterpretations or fake. It was funny Jay and I were talking yesterday like oh did you see this the video with the girl driving the tank? And I'm like yeah Jay that that's not real. He's like oh no. It's a Russian YouTuber basically who recorded that like a month ago and nothing to do with the invasion of Ukraine. But that's the thing, if something feels really good, like it's iconic, like it just fits perfectly it's probably fake, right? Or there's you know if it feels too good to be true it probably is.

BW: You know what, what I've been struggling with on this is, is how best to support the people there, like it's so hard and to find a charity that you trust that you think is going to actually get the money on the ground in a way that is going to benefit people.

C: Have you seen what a lot of people I know have been doing which I think is very cool.

BW: No, what?

C: They've been going on Airbnb and directly renting rooms from Ukrainians and then just leaving messages that say I'm not actually going to stay here I just wanted to support you.

BW: Oh yeah you know when I booked the Airbnb to come out to this trip to Connecticut and right on the front page it says you know get rooms in Ukraine right now.

C: Yeah so because we know that that money goes directly to the pockets of the people who own those homes or those apartments that are that are in Ukraine.

BW: Oh that's interesting.

C: Kind of cool yeah, yeah.

B: I like it.

S: There's one thing I wanted to follow up on because Cara you mentioned briefly like what percentage of the Russian populace that the public supports the invasion.

C: And I didn't mention a percentage by the way.

C: No no you just said like the majority whatever, large portion or something yeah used, you know, vague terminology, because that's all we have, is just the impressions, you know. There's certainly been a lot of protests, thousands of people being arrested, that's unusual you know.

C: And against like pretty scary odds, it's not just like if somebody speaks up there's no you know retribution for that, like they could go to prison they could face something worse. Scary.

S: But, hot off the presses, as we're recording this, an actual survey.

C: Oh no way.

S: Coming out of Russia. Independent. And again according to the article I'm reading on the Washington Post it's, they say that this is a good, reliable, independent you know organization. And you know they're having to keep the details unfortunately hidden just because they're you know that Russia is clamping down on information coming out of Russia. But here it is. About 58% of Russians approve of the invasion of Ukraine, 23% oppose it. The rest are either, don't know or on the fence, you know, don't have an opinion or don't want to say are on the fence. And this, confirming what I've heard in more vague terms but it's the people who are against the invasion of Ukraine are younger and more urban.

C: Right.

S: And then the older and more rural people who are in support of it.

C: Which makes sense because they've been under this sort of propaganda regime for a really long time, older people obviously I think that we do tend to see those tendencies you know, we see similar things in in the United States and in other countries. Like this more kind of patriotic and singular sort of allegiance to whoever's in power. But I also worry that even those numbers. Like how honest can people be right now?

S: Yeah we don't know.

BW: Well and how how did, they say how big the survey is?

S: Yeah it was 1 640 adults, it was a phone survey.

C: It's just like, I don't know, if somebody called me up on the phone and I lived in Russia and they were like "Do you support Pputin" I'd be like "Is this a trap? Yeah of course I do".

BW: 100%, yeah.

C: You know like it's scary to speak out so yeah I'm not sure.

BW: Also who's, who's answering the phone?

C: It's true.

BW: You know like it's 2022. I don't know what the deal is within, in Russia, if it's here, but your phone, random phone rings, if you're old you're maybe more likely to answer it.

C: Right.

B: Yeah good point.

S: Yeah, there's obviously an unscientific survey but it's what we got.

C: And it does it does kind of rock Steve with with some of the emails that we've gotten from people who were like Cara, you and Jay were talking about your sort of empathy for the Russian people whose own you know whose leadership is leading them in a direction they don't want the leadership to go. But like do not underestimate the power of propaganda. Like a lot of people there actually support Putin and support this war. And I'm sort of in that that interesting place, like we often talk about, let's say, anti-vax rhetoric. Like who is duped and and who's the duper. And at what point are they responsible for being duped but then perpetuating rhetoric.

S: Yeah so victim and perpetrator are blend together.

C: Yeah. Yeah and when you've been living under a propaganda regime for a long time it's hard to not believe what you're fed, because all of the media says the same thing.

S: Yeah they're basically being told, the narrative is that this they are liberating Ukraine from Nazis, right? That's literally, that's the propaganda. And it's just a special, it's not even it's not an invasion, it's not a war, it's just a special military operation to liberate those Ukrainians. And they also are being told that Russians in Ukraine are being slaughtered. If you speak Russian like they'll kill you, you know they, so it's, it's also, they're doing a humanitarian effort to save Russians in Ukraine from genocide. That's what they're being told. That's what they're being told. Yeah so that's all you hear. Even if you think, all right this is half, it's still like it's a framing thing, it's an anchoring thing, right? So you're anchored to the propaganda as your starting point, and even if you try to correct for it. You're still I guess but it's probably a good idea that we're going in there, you know what I mean? Whereas you know it's harder to like completely detach from the swamp of propaganda that you're being buried in, and have some kind of independent evaluation.

B: But if you have access to the internet and you see.

C: But they don't.

B: They don't have access to the internet?

S: No. Well it's being it's being censored, they can't get on Facebook, they can't get on Twitter.

BW Especially in the last couple of weeks, stuff has been taken away.

B: Oh wow, I didn't know that.

C: And they also just, the very last independent news network just went offline, right? Yeah, it's scary. And and this is coming from people who live in the United States where I think it's important for us to to also kind of reflect on ourselves and exercise some humility that we ourselves have our own propaganda that we you know our own anchoring problem.

B: Oh yeah.

S: Yeah.

BW: For sure.

C: And yes, it's completely different because we do have a free press. But, in some ways it's not that different, we've had a long national narrative of like American exceptionalism, and this is an anchoring problem that a lot of Americans come from. And so we have blinders on when we do terrible things politically and geopolitically and we're moving from that.

S: Our international listeners frequently remind us of our American narrative anchoring, absolutely. And we try to be as aware of that as we can be and we love you know getting feedback from other perspectives. But also, it's not just an American narrative Cara, it's, there are sub culture narratives within America. There is a definitely a republican narrative, a democratic narrative, a libertarian narrative, a religious right narrative there's─

B: A Halloween narrative. (laughter)

S: ─and those are narratives those are way more intense, those sub ecosystems of information are a much more insular, much much more extreme, you know much more unforgiving of information that goes against the narrative.

C: It kind of also just goes to show how dangerous nationalism, patriotism can be, that there's a dark side of a singular pride that people feel in their country, especially when their countries are a large military power.

S: So I think yeah for me I think there's always a sweet spot like there's a balance. Like I think it's okay to be patriotic but not nationalistic, right? Like there's a point where like yeah I can take pride in my culture, and the good things about the place that I live etc., but you have to stop short of it becoming a prejudice─

C: Or we are somehow better than others.

S: ─or becoming jingoism. Us versus them. It's more like, we're great, you're great too. It's just all the diversity of humanity. And wouldn't it, wouldn't it suck if we were just one homogeneous you know culture, that would be terrible, it's great that we have these deep cultural differences and histories, and it's you know, but we have to learn how to celebrate that without making it in us versus them, or demonizing or othering you know different groups.

BW: I mean for for me in my, in my lifetime, I feel like the real shift was right around after 9/11, was when it started to be it started, I mean at least in my adult maybe, I was born in 1975 so that was a you know a young adult at the time, and that's when it started to feel like people were pushing way too hard on some of the pro-America stuff. That felt like an inflection point to me, but that also might just be my age.

C: Yeah, yeah it could be that that's when you you know had those formative experiences, but you're right I think obviously 2000, 9/11 was a watershed moment for a lot of people.

S: But my my recollection was there was kind of a good kind of patriotism and love of country after 9/11 but of course that gave way eventually to old [inaudible]─

C: Mass destruction.

S: ─reasserting themselves

BW: Pretty quickly, yeah.

S: Yeah. All right let's move on, got a lot of interesting science news items to talk about.

News Items

Solid State Batteries (14:06)

S: Jay you're going to start us off, telling us about solid state batteries. Yes, more battery news.

C: Yey.

J: Yeah Steve, this one could be interpreted as good news. So as much as we'd like to have a profound breakthrough in battery technology. It's just not likely that it's going to happen. But we have more and more companies investing in battery development. And what we're seeing now is that there's an incremental change that's happening in batteries quite frequently, right? We're getting, we're getting like you know improvements in the technology coming from different parts of the battery. And this is great news because all of those small changes add up and as we're seeing now, battery technology is making some real strides. What properties do we want out of modern batteries? You know, what do we want our modern batteries to be able to do? Well a big one is something called energy density.

S: Energy density is the maximum energy but per the volume, whereas specific energy is per mass.

J: We of course wanted to recharge as fast as possible. We want the battery to last a long time. The way we gauge this is how many charge-discharge cycles can the battery perform. We'd like batteries to be inexpensive, and be made out of materials that don't harm the environment, and easy to get materials of course. They need to be able to operate in a variety of temperatures. They also need to be manufactured in large quantities. And this is a part of battery production that could just literally stop new technologies if they can't ramp it up and make tons of batteries in in a factory setting, then they can't sell it, right? If they can't make them, they can't sell them so that could kill any technology right there. We want long capacity retention, this means the battery holds onto its charge while it's not being used. And the last one is that we would prefer they don't catch on fire right when they're in our pockets, because you know this actually happens.

BW: Always a good thing.

C: Or in our garages, like my car was gonna do which is why I had to take it in for a recall.

S: Oh boy.

J: Right now lithium-ion batteries are the leading battery design that checks most of the boxes, most of the things that I listed above. There's actually four different types of lithium-ion batteries. They use different minerals and all of the properties that they have are different depending on which minerals that they use, right? So lithium-titanate, lithium-cobalt-oxide, lithium-nickel-manganese, cobalt-oxide, lithium-iron-phosphate, each one of these can do different things is better at certain things than other things. All of these batteries have a liquid electrolyte core, that's job is to conduct charge between the batteries electrodes. Researchers are working on a solid-state version of the lithium-ion battery which is really cool. Once they work out the remaining kinks, these batteries will be able to have two times the specific energy and energy density compared to today's lithium-ion batteries. This means that these batteries are going to be able to do a lot more for us. The solid-state version can do this because they can use much thinner separators between the electrodes, they can also use an approved electrode that's 100% made of lithium instead of a lithium graphite combination. The all lithium electrode is just simply lighter which makes it better. Researchers say the solids, the solid state batteries will have a longer lifespan and will also be safer because they're more stable which means less pocket fires. So in the real world this means that in one battery upgrade your cell phone and laptop will have twice as much capacity, it's a big deal, you know this is the type of bump that we've all been waiting for. Now consider what this will do for electric vehicles, this is where it really shines, the solid state lithium-ion battery will add 50% more range and on top of that it'll weigh 25% less, which will actually give your car even more distance.

S: Well Jay but that example, it's you go from 350 to 500 but with a 25% decrease in your battery weight. Which actually would extend your range a little bit more. So you basically, you could keep the same battery size and have didn't have a 700 mile range or you could go to, where you could have the same range and have a half a battery that's half the size and weight. Or you could compromise somewhere in the middle. The question is going to be where's the sweet spot right, where, how much range do you, would you, do you want to pay for. And you know I've been driving an electric car now for about almost a year with a 350 mile range, which is great, it's awesome but on long trips, we've done it and it works but we would definitely appreciate more range on long trips. I would say something like 500 might be the sweet spot.

BW: Have you gone more than 500 miles in your in your car?

S: Yeah, you just got, you just have to know where you're going to recharge, you know.

C: Yeah you have to plan around it. I've done, I've done a couple trips that were not super, super intensive but even like I think my range is three no, not even, like 260? And if I'm gonna go someplace that's like 240, I'm not gonna risk it, I'm gonna stop at a super charge yeah and and have lunch and and do 80% you know and then continue on my way. Which is easy because it takes like 20 minutes and it's like five dollars.

C: But the the thing that's gonna really make that better is more recharge stations. Like one, the first time we did a long trip with our with our Tesla, the hotel we were staying at said that they had recharging stations. So we get there and they had one recharging station.

BW: Oh no.

S: Which was free and we used it to completely recharge our car overnight. But what if it weren't free? What if that, what if someone else are using that one station and the one night we had to recharge our car, we did, what would we have done? That would be solved by more recharging stations.

C: And that's, and that's really the case out here on the west coast. You're not nearly as beholden because there are, the infrastructure there's so much better here.

S: Yeah, this was in Maryland.

C: Yeah, yeah yeah.

J: Like I said these batteries are not ready for prime time, there are, there is one real hurdle that needs to be resolved and they are working on it. The solid state batteries have an instability that happens between the solid electrode and the electrolyte. Lithium dendrites which are metallic microstructures that form on the negative electrodes during the charging process. These form inside the battery. So these little dendrites can reduce and significantly do reduce the battery's lifespan. If this issue can't be engineered away, it'll kill the solid-state lithium-ion battery for good. The researchers have found solutions that either cost too much or don't scale up for manufacturing, and that's you know the problem I mentioned before. But don't let yourself lose your charge just yet because a new study shows promise that a solution was found that has a very small price increase to the manufacturing process. What they discovered was that during the battery manufacturing process, the ceramics that are used inside the batteries is the real culprit. During the manufacturing process the ceramic components are heated. And until they get kind of soft and sticky, so they can stick to themselves. Now when they can stick to each other when they're at that temperature the ceramics are now picking up CO2 from the air that they're surrounded by. And that CO2 makes cut it forms a compound with other material, and that material actually reduces the battery's ability to conduct electricity. So you know when I say this it's going to be really obvious but they have, they came up with a simple solution here, they're just going to put it in a an environment like an all oxygen environment, so there's no CO2 there so the ceramics can't interact with the CO2 and actually do bad things. So I even have more good news. Literally today as we record this March 8th, 2022 a company called Gogoro and another company called Prologue Gym, these two companies released a solid-state, lithium-ion battery. Very, very cool. Now I, we're going to learn more about this, you know this is brand new information, I'm not 100% sure what the situation is. Steve you actually had some info on this.

S: So their battery, they're claiming 140% more capacity than lithium-ion batteries. I guess it's because it's always compared to [inaudible].

B: 40%?

S: 140 increase. They have a system of swappable batteries for like motorcycles.

B: Oh swappable.

S: Yeah so you basically just pull it out, you get a fresh one, and you're good to go in minutes you're done. So that and that's something that we've been talking about for decades you know. Maybe this is the problem to the range anxiety is that you just have swappable batteries. They have them, it exists. These are solid state lithium ceramic batteries, solid state. They're, it's a working technology. I think they're using the older solution which is to coat the electrodes, that works, that solves the problem, it's just expensive. So this is basically just a cheaper way to solve the problem. This is more than an incremental advance, like this, we're shifting to a new technology from lithium ion to solid-state lithium-ceramic batteries. And, and we're going to get more than an incremental jump, when the technology is fully working and scalable. So I think again it's working, but this will make it more scalable, because it makes it cheaper to mass produce, then we get that you know 100 to 140% increase in range. You know, whatever, some combination of reduced battery cost in size and increased range. And I think we're already way above the line in terms of EV technology being you know widely adoptable. But this would make it even more so, right? This would probably wipe away the last vestiges of range anxiety and the technology will be fully there.

C: Which is good because like, I don't think we're gonna have gas cars much longer. I think that EV is definitely going to [inaudible].

B: Oh yeah, days are numbered, for sure.

S: Yeah could be 30 years, maybe 30 years.

C: Until they're completely gone maybe but I think that electric cars are going to own the market within the next 10. What we're already seeing.

BW: Some manufacturers haven't they said all electric by some given year, right?

B: Ford was saying 2050 I think.

C: A lot of manufacturers have decided to do that.

S: Well listen so in terms of like all new car sales, we'll be shifting, by the time most new car sales are EV that'll be like 20, early 2030s, something like that is what we're projecting. But even when we're a 100% new EV car sales it will still take 20 years from that to replace all of the internal combustion engines that are on the road. So that puts us into the 2050s, which is why that's what people─

C: I see.

S: ─I wish we were 10 years ahead of where we are though in battery technology, would be nice but still, we're in a good place though and it's going, it's getting better, it's definitely that we're on the steep part of the curve in terms we're living through this transition you know, it's going to happen.

C: And we can't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Like there are good cars right now there are good options available.

S: I love my Tesla I absolutely love it.

BW: Well and especially when you think about even five years ago, it's it's just stunning how much there is now.

S: Absolutely.

C: My car has four times the range that my first electric car had, four times the range, for the same price.

BW: Yeah.

C: Amazing.

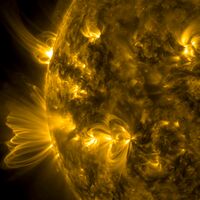

Are Coronal Loops Real? (24:56)

S: All right Bob, tell me, this is kind of a weird one, are coronal loops not real? And what are coronal loops?

B: Okay let's get into this, this was fun. So the Sun was in the news this week obviously, this time it's a stunning hypothesis actually, that that the beautiful coronal loops that are produced on the sun may be mostly illusions, potentially forcing a dramatic new take on what's happening in the atmosphere on the Sun. This is from the actual physical journal the title is "The Coronal Veil" and led by Anna Malanushenko, she's a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, NCAR. Okay so coronal loops, I'm going to read you a wonderful description of this from wikipedia which is nicely succinct, let's see corona loops are huge loops of magnetic field beginning and ending on the sun's visible surface, the photosphere, projecting into the solar atmosphere, the corona, this hot glowing plasma is trapped in the loops making them visible. Coronal loops range widely in size, up to several thousand kilometers long, they are transient features forming and dissipating over seconds or days. Okay so that was a really good description of coronal loops, so but maybe that maybe that definition is going to need a radical change in the near future. So we all know that the Sun is hot, right? That's a no-brainer. But it's, did you know it's so hot that it rips apart molecules creating the most common state of matter in the universe, what is it, say it.

S: Plasma.

B: Plasma, yes. So now the the plasmas electrons and ions create electric currents which then create powerful magnetic fields. And those magnetic fields that can extend to the either the far reaches of the solar system, or to stay nearby where they leave the surface briefly extending into the corona and then dropping back to the surface, and that's what we're talking about. The plasma can get stuck in these loops of magnetic field, and it can leave, and it can't leave through the side, so it's got to just follow and fill these magnetic arcs creating the beautiful these beautiful structures that we see so often on on the Sun. Now these loops aren't easy to study though and that's because of the corona. The corona is the outermost atmosphere of the Sun and it's usually invisible because of the glare from the surface. But, Cara has seen the corona with her naked eyes. When you saw your a total solar eclipse, that's what you see of the Sun, you see the corona peeking out because the glare of the Sun is being covered by the Moon. So that's, that's the only time you can really see it with your you know unless you have you know specialized instrumentation.

S: And Bob I understand that when that happens you spontaneously break out into singing "My Corona".

B: Oh no way, is that what they do?

BW: That's just science Bob.

B: In that case, what could I say?

S: And Brian is an astrophysilcist.

BW: Sort of.

B: Oh my god I love that. All right, so the corona is optically thin and that means that it's easy to see through, which is wonderful but it also makes it hard to distinguish structures that are overlapping each other. And that's where this wonderful 3D simulation comes in called MURaM, it's a groundbreaking advance, really interesting advance here that can simulate the in the entire process of loop formation from under the surface to well outside the surface into the corona. So it's like it's similar to, say, if you could model the full gestalt of a zit from the oil glands beneath the skin surface up to the zit itself and then beyond your face when the zit pops. And that's my favorite analogy of 2022 so far. Now MURaM can simulate from 10 000 kilometers below the surface up to 40 000 kilometers into the corona. And for the first time it captures the entire life cycle of structures, like solar flares. I'm not sure why they they said solar flares because I think, I don't know if MURaM was designed to specifically recreate in the simulation solar flares. Or are they, when they're, they're applying that to these coronal loops, I'm not sure but but MURaM was, it's an amazing advance. So now using this, using the simulation they could actually take slices of the corona and isolate those loops and kind of do away with the problem of the thinness, the optical thinness of the corona. And when they did that, they found something that could be I think could be Nobel prize worthy, I think. Now many of these loops in fact were not loops at all, not all of, they absolutely think that they found or found very good evidence of classic loops as I described or as wikipedia described a few, a couple minutes ago. But a lot of them were not loops. What the MURaM simulation of their model showed was that many of the loops were in fact sheets of plasma that had these wrinkles in it, essentially folded over onto itself. These folded over sections look like thin bright lines, exactly how the discrete loops of magnetically confined plasma looks. So now that's the essence of what they are calling an optical illusion. It looks like a a genuine coronal loop caused by these magnetic field lines and the plasma but they think it's not. Many of these are not that at all it's this, it's the like this the title of their paper, the veil, the solar veil, it's these, it's like these sheets or veils of plasma that are folding over itself creating you know an over density of plasma that makes them very bright and makes them stand out. And the veil itself, obviously, apparently the veil is very difficult to see. Or right now perhaps impossible to see, it wasn't quite obvious. So the lead author Malanushenko said:

"I have spent my entire career studying coronal loops. I was excited that the simulation would give me the opportunity to study them in more detail. I never expected this. When I saw the results my mind exploded. This is an entirely new paradigm of understanding the Sun's atmosphere."

Now actually, I wasn't aware of this, but this actually answers some questions that scientists have had over the years about these coronal loops. For one, the magnetic field lines of these loops should spread out the farther it is from the Sun, right? I mean that's just how it works. You guys imagine in your, in your mind that classic image or the experiment you did in in high school physics where you've got a magnet and you throw some iron filings and the filings line up along the field lines, right? And you've got that shape, that classic shape, the you know the farther away it was from the magnet, the wider the field lines were, right? Because it's not quite, it's not quite as strong. So that was not happening with these coronal loops, they should have spread out the farther they got away from the Sun's surface, the visible surface, the photosphere. And it wasn't spreading out, and it wasn't becoming dimmer. It was just as bright at the farthest extent of the loop as the nearest extent. And so that, that didn't make a lot of sense and this kind of would explain that actually but like all good signs so that this concept raises new questions then. Like what causes the shapes of these folds, and the densities of the folds, and how many of these loops are real, and how many are just the these folds, these optical illusions. So yeah, so if this is true then there's lots of new questions to be answered, lots more research to be done. Now remember, this is just a simulation guys. No matter how sophisticated it is, it's a simulation. The best answers are going to come when they can observationally distinguish a loop from a veil fold if you will, using new types of observations and new analysis methods that haven't been even invented yet. So this is this is a simulation, it's a powerful simulation that's really sophisticated, but these have not been observed, so they're gonna have to come up with ways to figure out all right how are we gonna distinguish these, so that we could really get some real answers, real answers that you know that this the simulation has pointed us to this potential, this potentially new you know groundbreaking discovery. So, I'll end with a Malanushenko quote, she said:

"We know that designing such techniques would be extremely challenging, but this study demonstrates that the way we currently interpret the observations of the Sun may not be adequate for us to truly understand the physics of our star."

Cool stuff, wow, that's, that's fascinating to think that a lot of these loops are not really the loops with that we thought they were.

BW: And it's not, am I understanding this correctly that it's not just the, it's, so they, they did the simulation of the MHD magnetohydrodynamic equations and so it's the both the magnetic field and how the plasma is moving along the magnetic fields. These are both different from what we understood before, right? Like the whole thing.

B: Yeah, the whole thing, yeah.

BW: There's a whole new structure here that we didn't understand, that's awesome.

B: Absolutely.

BW: It's also worth pointing out, I mean these this set of equations for you know charged fluids is super, super complicated. That's why this is taking so long to get this stuff right. Like you have these, you know fluid dynamics by itself is non-linear and then when you complicate it further by having electric and magnetic fields and the fluids are charged it's it's just it's a real barrier.

B: It's fiercely complex and this is why no one has been able to run this simulation that's so thorough. Like I said 10 000 kilometers below the surface, 40 000 kilometers into the corona. No one's done that because it's so complicated. That swath of star has so many you know densities and temperatures and magnetic fields and all these things going on. Nobody could simulate that until recently.

S: All right thanks guys.

COVID Anosmia (34:25)

S: Cara so we all know that one of the primary symptoms of COVID is that you lose your sense of taste and smell. If that happens, get a COVID test, you probably have COVID. But we don't really know exactly how that happens, but maybe we're getting close to understanding this.

B: Oh cool.

C: Absolutely, yeah, yeah. Researchers have been really trying to figure out exactly what's going on and why this seems to be a sort of as you mentioned like hallmark symptom, not everybody gets it, but often people do, and it usually goes away, but it doesn't always go away and so like what is going on. I'm curious, so I have not yet gotten COVID. But of those of you here in the the in the show have any of you had an anosmia when you had COVID?

BW: I did.

C: You did.

BW: In fact fact that's when I tested positive for it. I think I'd had it for a few days and was testing negative, waited a day and then woke up one morning couldn't smell or taste my coffee and I was like whoa-oh and that was the day, the first day tested positive for it.

C: And then how long?

BW: Lasted about a week, and I was back to 100% for sure within two weeks.

C: And so would you say that the other symptoms resided first and then your sense of smell came back or it all kind of came back at the same time?

BW: No the smell came back a little bit later like yeah for sure the other stuff, I didn't, I had like the, felt like sort of a cold kind of symptoms version of COVID, the real mild one. And that lasted a while, that went away and then maybe a few days later smelling taste came back.

C: So researchers across several different institutions, Colombia, NYU, Mount Sinai, Baylor, UC Davis, they collaborated together on, actually there's been a series of papers and this is just the most recent one that came out in cell just last month. Trying to look at what mechanistically is going on. I think the the kind of original hypothesis was that the actual sensory neurons in your nose, the neurons in your nasal epithelium, these cells that have sensory receptors on them, were somehow being infected by the virus. And that was, that was the leading hypothesis until they discovered, nope, virus not getting in. Virus actually doesn't get into most cell types, of this specific COVID virus. So it's been very kind of like, a coronavirus, so it's been very confusing for researchers to figure out why sense of smell getting knocked out, that's a pretty intense symptom, what exactly is going on. And so they did a couple smart things. They looked, unfortunately at autopsy of human nasal epithelia, to try and understand like a little bit more forensically what was going on. But they also did some experiments on golden hamsters, because who knew, golden hamsters are apparently a very good animal model for human COVID infection. They have a similar response.

BW: That's, that's a species of hamster?

C: Yeah, it's golden.

BW: Sounds cute.

C: Yeah, it is. Well in all of the renderings, because the paper has little pictures around. It's funny though the hamster is actually gray in the rendering so maybe I need to look up what a golden hamster actually looks like. And so what they did is they, you know, they gave some hamsters COVID, then they looked at what happens kind of day by day, both behaviorally and physiologically and anatomically. To try and figure out exactly what is going on. So, so the first thing that they realized is the cell itself, the neuron itself is actually not getting infected by the virus. But there are changes that are taking place. The neurons aren't dying, the neurons remain healthy but the actual receptors, which are encoded by proteins are changing. And they're down regulating. So the receptors themselves are no longer present to bind to these different smell molecules. And they're like well what the heck is going on there. And what they realized is that actually there's a genetic response that occurs to inflammation. And inflammation seems to be the major actor here. That similar to that cytokine response that we see in a lot of different areas of of kind of the disease process, and especially in COVID we're starting to see more and more and especially in long COVID. In other diseases, where you lose your sense of smell, I shouldn't say diseases but infections where you lose your sense of smell, it's mechanistic in that there are like you literally get snotty. There's like mucus that that like blocks up your smell receptors. Like there's stuff in your nose that's preventing you from being able to smell. And you've got a stuffy nose but many people with COVID don't have a stuffy nose.

BW: Yeah, I didn't.

C: Yeah, right? There's nothing going on, so you're like why can't I smell, my nose feels fine. But what happens is that you get this viral infection. And you immediately have an immune response. That immune response sends these different factors, these different cytokines that are there to help protect the cells from you know further a viral decimation. But sometimes can actually harm us in ways that we don't really account for. And in this specific case, there's a big focus on these cells called sustentacular cells. By definition sustantacular cells are simply like supportive cells, so they're cells that are near other specialized cells that sort of maintain structure, but they don't necessarily have a specialized function. So when you look at the nasal epithelium, you have all of these different sensory neurons, the smell neurons with these smell receptors on the very very end. And in between them there are all of these sustentacular cells. And what looks like is happening in this specific kind of disease process is that the sustentacular cells are becoming infected and they are releasing a signal that kind of tells the neurons that usually detect odors to reorganize their genetic makeup and stop expressing olfactory receptor genes. And so when they stop expressing those genes, they stop creating the proteins and the receptors themselves are down regulated and then you can't smell. It's a fascinating process that these local cells are actually telling these functional cells to change at the genetic level, usually temporarily, I think 90 plus percent of cases are temporary. And but because this the neurons themselves do not die, they are not infected and they remain intact, so often after the infection is gone, after you have that local immune response, they're able to reorganize back to normal and you can smell again. Pretty cool.

S: Yeah, it's really interesting because yeah the first assumption is like, the virus is infecting those cells. Which, but the sometimes the simple explanation turns out not to be true.

C: Right. Absolutely and you know, where I think we're learning that more and for more and more with inflammatory response in especially infectious disease, that you know in some simple infections, there's like this normal course that we can look at and say okay, whatever cell gets infected, whatever proteins are changing blah, blah, blah. And then we see these other examples where there's a cytokine storm or where there's a you know a hyperimmune response that actually leads downstream to more symptomatology. And sometimes to more difficulty in recovering from the disease. And so this kind of area of infectious disease research, which is looking at these inflammatory responses these sort of natural responses to infection that actually cause, can cause quite a bit of damage, is a really interesting and I think quite cutting edge area of research because it's not uncommon that, as I, like in a New York Times article that covered this, they called it "the immune system's friendly fire".

BW: Do people know much about, I mean, I'm sure they know a lot, I don't know anything about treatments for, for this, does this help at all with people who've lost their sense of smell for months or in some cases a year now?

C: Well from what I understand there are no treatments for anosmia.

S: There's no active treatment, no.

C: Yeah, like across the board even in other, other incidences, like pre-COVID you know, when people have lost their sense of smell due to neuronal insult or due to different problems with the cellular architecture, from what I understand there is no treatment for anosmia at all.

S: You learn to live with it, that's the treatment is, learning how to live with it.

Alcohol and the Brain (43:48)

S: So the last news, I'm going to talk about the effects of alcohol on the brain. And this is an interesting topic on a number of levels. I remember going back to like my medical school days, which was, ekhm, 30 years ago. When the the bottom line kind of shifted over time, right? So the question has always been, is alcohol directly toxic to brain cells? Or are alcoholics have you know, they have to, clearly have bad brains you know, they have impaired cognitive function and brain atrophy etc. Is that due to things that go along with alcohol, right? Is it due to malnutrition and I know that was sort of the thinking when I was in medical school, that's basically the malnutrition and it's not the direct toxicity of alcohol. But that really has been an open question and the data has gone back and forth, over the, over the years on that. It's hard to like fully tease it apart because alcohol is so co-morbid, like heavy use of alcohol, alcoholism. So co-morbid with other health things that would affect your overall health. But what we have now is a new study which is the, which is the largest study to look at this directly at this question. There are 36 678 subjects in the study published in nature communications last week and they had, this comes from a UK data page where they had data on imaging from the UK biobank. They have data on imaging so they could have overall brain volume, gray matter volume and structure and white matter structure in the brains of over 36 000 subjects. And also reports of their daily alcohol consumption, so they were able to as well as lots of other demographic data and that's important. So they were able to see is there are correlation here. And because they had a very powerful database with a lot of information, they were able to control for a host of possible confounding factors. Such as age, height, handedness, sex, smoking status, socioeconomic status, genetic ancestry and the county of residence. This is again in the UK. Just you know if any of those factors had any influence on the you know these measures of brain volume they would control for that. And then they tried to isolate the amount of alcohol people used on average as a factor and see what does this correlate with brain volume basically. They broke it down into units of alcohol, of daily alcohol use, with one unit basically being half a drink, like half of a beer or half of a glass of wine. And what they found was that as little as two units or one drink per day on average was associated with a statistically significant decrease in brain volume. There was a pretty clear dose response curve, and it was non-linear, so that as the number of units of daily alcohol increased this effect became greater, right? They also looked at the data in an interesting way. They said if we use all the other factors to predict what the brain volume should be for this person, based upon their age, height, sex, smoking blah blah blah, then we could say how old does their brain look compared to their actual age, right? That makes sense? So they say if the, the, what does the factor of alcohol use correlate to in terms of like, if we replace that with age, what would it say like the equivalent in terms of the effect of aging. So one, that there was no difference between zero and one unit. So zero a day and a half a drink a day, there was no statistically significant difference. Between zero and two units, or one drink per day, your brain looked six months older than if people who've had you know zero drinks per day. So that doesn't sound terribly significant you know. I personally find every one of my brain cells to be precious but (laughter) you can make that decision for yourself. But here's the thing, at four drinks per day, four drinks per day, the subjects brains looked 10 years older. 10 years. And now we're talking that's significant, that's a significant amount of of a volume loss and aging you know in on the the parameters that we were discussing. So and this, so this seems to be independent of all these other factors. And this supports the conclusion that alcohol itself is an independent risk factor for you know damage to the brain over time. As interesting as all that is, what's also interesting just to think about the general scientific questions about this kind of data, and how we address these questions, to put it into context. So one context that's important to note is, the previous data right, it's never been controversial at least not over the last 30-40 years that heavy alcohol use is associated with brain damage.

C: Oh for sure.

S: Alcohol itself, you know when you get to heavy use. But the question was, how much does that extend to less and less amounts of alcohol use. This is a generic question that comes up with every time we look at a toxin and say how toxic is it, right? And so we want to know, what, is there a threshold and is the toxicity linear. So for some substances for example we say it's linear, no threshold toxicity. Meaning that again like twice the exposure gives you twice the toxicity and there's no lower limit as far as we could detect.

BW: Such as, what's an example of that?

S: Well smoking is now considered to be a linear non-threshold toxin for example. Like there's really no lower limit. But the question is how do we know if there's a lower limit or not. Because for any toxin it's going to be easier to detect at the higher exposure levels and get increasingly difficult to detect. Essentially you could say that the signal becomes smaller and smaller. At some point it disappears into the . That doesn't mean the toxicity goes away, it's just an absolute statistical mathematical phenomenon, that it's going to be more difficult to detect, the effects of toxicity at the lower end of the exposure spectrum. And so that signal's always going to disappear as you go down. Whether there's a lower threshold or not.

C: And are you talking more in like epidemiological studies because there is so much noise, or even in like animal models where we can control for kind of all of the different variables?

S: So that's a good question. So in any model, but, the question is, yeah, I would frame, I'm, the way I'm framing the question is, you know how do we know where that lower limit is? And and the way we do that is to have research with low noise and or high power. So those are the two variables. So one way to get low noise is to have a rigorous design, right? To do an experimental study for example. So we can't do that in humans you can do that in animals. But animals don't always behave like humans and like for example with smoking we've had a hard time proving─

C: Absolutely we had a hard time.

S: ─that smoking causes cancer through animal models because they just don't behave the way humans do. And also it's unethical you can't say, you can't randomize people to how much alcohol they're going to drink. Here, have five drinks today I want to see how much it damages your brain, right? You can't get approval for that study. So we have to content ourselves with other kinds of studies, mainly observational, right? Where we're just asking people how much they do drink and then correlating that with something. That doesn't mean we can't ever get to a confident causal conclusion. It just means we have to triangulate a lot of data, and we have different ways of looking at it. So if you, you know if you look at it in multiple different ways like one thing that's always nice to see if there's a clear dose a consistent dose response curve, that supports a causal toxin effect, right? Because usually when it's an epiphenomenon, it's a confounding factor, usually it doesn't follow a strict dose response curve. When it's a biological toxic effect, it usually does. So again it's not iron-clad but it definitely pushes us in the direction of saying this is a direct toxic effect. The other way you could do is to have a really powerful study and, and that basically means more subjects. So that's what this study is doing, they, they're saying all right let's, if we can come up with a database that that we where we can get tens of thousands of subjects make a super high powered study, will be able to probe further down the you know the spectrum of lower and lower exposure. And when they did that they found yeah, it tracks, you that continues all the way down to the limit of the power of the study. And so that suggests that the threshold is at least really low, if not no threshold you know from a practical point of view. So that's, again what this study kind of suggests is that as though the more we look, the more subtle toxicity we're seeing. And if we had a even more powerful study would we see a statistically significant change, even at a half a drink a day, maybe. Or maybe, but we don't know. And it's, it's certainly biologically plausible that there is a threshold effect, right? Below which there's essentially zero toxic effect. But we know that that threshold is really low for alcohol, right? It's less than one drink per day, if there is a threshold. At some point the the lower threshold, it becomes so small, it's like a distinction without a difference, right? So we're kind of getting there with alcohol. So at this point, what does all this mean. I think it means that the scientific evidence now I would summarize it as saying what's the relationship between alcohol and brain health, that heavy alcohol use is definitely bad for your brain health. Definitely causes brain toxicity. Moderate alcohol use probably does and the effects are significant, you know, when I say moderate like three to four drinks per day kind of thing. And then when you go down from there, like mild drinking, one drink a day or less, you know, it may, there may be a a subtle negative effect there but people can decide for themselves what choices they want to make with respect to that. But we can no longer say with confidence, not that we ever could, but we definitely can't say we're confident that like one drink a day is benign. We can't say that.

C: Or even you know, I think a lot of times people have argued that one drink a day is good for you.

BW: Yeah you hear that in France they drink you know blah blah blah, right?

C: Oh and the resveratol in the wine and you know all of these things that they somehow might outweigh the potential negative consequences and you know I think at the one drink level maybe the jury's still out but like it's not necessarily benign.

S: That evidence has moved in the direction of no, and here's partly why. The early data that showed that moderate, that moderate drinking was better than no drinking, like one drink a day was better than zero drinks a day was an artifact of the of the fact that the zero drink a day category was contaminated by ex-drinkers. People who quit, they were former alcoholics who then quit and so technically they drink no alcohol, but the damage is already done. Once you take them out of the data, that beneficial effect of alcohol mostly goes away or entirely goes away. And so that it made it from maybe to we really don't know now and maybe there isn't any benefit at all.

BW: And how long ago did people realize that? Is that recent?

S: That's like 10- 15 years ago. But it shows you─

C: How it stays.

S: ─yeah.

BW: Totally.

S: Those narratives get in the public, they take decades to go away if ever. We're still saying that was wrong 100 years ago.

BW: Well but also with that one it's like people want and, you know, people want to have a drink every now and then. You know they're like oh look it's good for me.

C: I mean think about smoking, people were still talking about how smoking was potentially medicinal, pretty late in the game.

S: 50s, yeah yeah.

C: Even after like the scientific community got it but the public just didn't and I think marketing had a lot to do with that.

S: We figured out that, my favorite example always is that antioxidants were pretty much worthless in the 1990s. Two decades later─

B: They're still touting that crap.

BW: I know.

S: ─more then two decades later, and it's not going to go away in the foreseeable future, it's just too useful branding, you know. But anyway so yeah, this is what the evidence shows for people who like to drink, you just have to deal with it, this is this is the data. Again you make your decision for yourself. We definitely you know I think any responsible physician would or would you know advise you not to drink heavily because there's definitely, more than just outside your brain, there's lots of organ toxicity associated with heavy alcohol use. It is a bad drug.

BW: I think if you have a doctor that's saying yeah please drink heavily that's probably a warning sign.

S: Right that's yeah it's a red flag right there. Even moderately is bad, like basically multiple drinks per day, yeah, that's pretty bad too. You know when you get down to like one per day or less is I think where it gets into the gray zone and then even then you gotta be cautious.

C: So Steve you and I don't drink it all, right? Like ever─

S: I don't dink, never have.

C: ─like I don't touch alcohol neither do you. We should enlist in some of these clinical trials. We're like unicorns.

Special Report: Update on String Theory (57:23)

S: All right Brian, you're like a string theorist and stuff, right?

BW: I am.

S: Give us an update, what strength theory been up to lately?

BW: Yeah so let me just give people a very short background on myself. So I was, well I guess I am a theoretical physicist. I was a theoretical particle physicist and I worked on mainly quantum field theory and string theory, with a specialty in four-dimensional super-symmetric field theories. So I did that for many years, then I quit but I do want to emphasize that I didn't quit because I was bad at physics (Cara laughs), I quit because I decided to be a full-time musician and YouTuber and now I dress up like a ninja in a comedy band. So those are my qualifications.

C: So this is because YouTube is way more lucrative than physics, yeah?

BW: You know what, well it, expected value, no.

C: Oh, interesting.

BW: But it can be. So I think─

C: (laughs) Theoretically.

BW: ─the upper, the upper end is probably much higher. Yeah, for YouTube. But on average, no. For sure.

C: More fun?

BW: Different kind of fun, you know? Like there's a, there's a kind of fun that's sitting in a seminar and desperately trying not to fall asleep and then there's the other kind of fun which is dressing up in a ninja costume and playing for thousands of people so, yeah, six-one.

S: I think some of our listeners might know your band, Brian.

BW: Yeah so my band, my main band is called ninja sex party and we're a two-person, I would say a two-person duo but that's redundant. A duo and we do like 80s, mostly 80s style comedy songs. And we've we're in year, I think it's 13 now. So I started this while it was a postdoc and then kept it going all through my faculty position and then eventually quit that job to move to LA from London where I was a professor. And do the YouTube thing full-time.

S: It's amazing.

BW: It was very scary but I'm really glad I did it. Anyway so the thing I wanted to talk about is, I haven't, you know, you don't hear much in the popular press or even in the science press about string theory these days. I mean this was all the rage probably, I wasn't quite old enough to really be paying attention but I would imagine starting in the late 80s, you started to hear things about this amazing new theory and for a while people were touting it as what they called "a theory of everything". So string theory, for those of you who don't know, the really simple version of explaining it, is that rather than being a theory of point particles which we usually think of the fundamental particles of nature being like an electron, a quark, or whatever. These are zero dimensional things, they have no spatial extent whatsoever. Like no matter how close up to get you get to them, they still look like little points. String theory is a theory of one-dimensional objects called strings, so basically little lines and maybe they close in on themselves and maybe they don't, they're different kinds. But that's the idea, is if you look really closely at the fundamental constituents of nature, they're not zero dimensional but they're one-dimensional. So, it turns out that once you assume that and then try to figure out the consequences all sorts of amazing things happen. Especially once you try to come up with a quantum mechanical version of this theory. And so in the 80s people discovered this idea. I'm vastly oversimplifying it by the way, really in some sense it was discovered many many years before that, but in the 80s people kind of figured out how to make it really work. And then they said all sorts of things like this is a theory of everything, it's going to explain the entire universe. There were some people who were optimistic that it would be like kind of just a follow your nose thing, start at point A, which is a string theory and then a few years later we have, we live in a three-space one-time dimensional universe with this set of particles and everything that we know. Now you would know if that had worked, because it definitely did not. (Cara laughs) It turns out that string theory was not just a straight line and in fact is vastly more complicated than people realized originally. And I'm not even talking about you know just the complexity of the language or string theory, there are all sorts of as we understand it now, different possible universes that might be consistent with string theory. So an interesting development happened here in the, I don't know it was probably 10 or 15 years ago, there was something that kind of erupted into the public consciousness. People often call it "The String Wars", where there were some prominent bloggers and other types, Peter White, Lee Smolin who were very anti-string theory and would talk about how, you know, to vastly oversimplify it again, to put it bluntly, they thought it was bullshit. And there were books published and a lot of ink expended on on this topic. But that was a you know 10 or so years ago and you haven't heard much from people on what's been happening lately. But by the way let me just say that the version of, you know, as with all things it's a bit subtle, but I think people who said string theory is not living up to the hype, were totally right about that. String theory did not deliver the promise of a unified theory of everything. And to this day we don't understand if it is a real theory, let me put it this way, if it describes the quantum gravity that makes up our universe, right? Is it right? We don't know. It might be right. But there is no evidence either way. It is certainly one of the very few quantum theories of gravity that we have but is it real? Is it true? We don't know. So people who are skeptical of that, were right to be skeptical. And we really don't know. But what happened along the way in the string theory is that string theory became less of an end in itself, as a way to describe the you know the universe that we see and just that it became kind of a fun toolbox for theoretical theories to, for theoretical physicists to to play in. So the there are all sorts of examples of this. The first one that comes to mind is, it's called AdS/CFT, it's a discovery pioneered by a lot of people, and still a very active area of research. The main person that's credited with finding it is Juan Maldacena at Institute for Advanced Study. And the idea behind AdS/CFT is that you, there's exactly the same information in a four-dimensional, by which I mean a three space and one time dimensional, quantum field theory, that is a theory of particles and a ten-dimensional string theory. And precisely where one theory is easy to describe the other gets complicated. So in other words you can start trying to investigate hard problems in quantum field theory with easy problems in string theory. And in fact the geometry of the ten dimensions. And people use this very successfully to understand all sorts of interesting things where like the the shape of something in this particular 10-dimensional string theory controls what's you know like the spectrum of particles in some given quantum field theory and that tells you absolutely nothing on its face about the real world, but it does help you understand a hard problem in theoretical physics, which is this quantum field theory. And we know that quantum field theories, quantum field theory absolutely do describe the real world. And in fact you know some of the best tested theories out there, quantum electrodynamics for example are quantum field theories. So what happened, to make a long story short, as string theory kind of progressed, people found more and more applications for it in a broader theoretical physics context. And so the question i wanted to ask or answer really, what happened to string theory, is that rather than become a theory of everything. Which I do not think of it as a theory of everything, I think people of my generation in string theory probably don't either. Certainly most of the people I knew in grad school, and I started grad school just after AdS/CFT was found and I started I guess in '98. People who started grad school around then were not raised in this kind of culture of "string theory is going to solve every problem". We came in thinking of it as a tool, and that is exactly what it's become. So the complicated question, there's still a lot of unknowns about string theory. In many senses it is not a rigorously defined theory, certainly not as rigorously defined as quantum field theory and so what people are using it for these days are, sometimes it's inspiration for solving hard problems in mathematics. The geometry of strings sometimes as interesting applications for difficult problems in algebraic geometry or things like that. Or as a tool to study the structure of quantum field theories. And the hard question is what is a string theorist? I don't know that anyone knows the answer to that anymore because it is someone who uses string theory in a very broad context. Sometimes just as uh as inspiration.

C: Brian Greene.

BW: Yes Brian, so Brian Greene.

C: That's a string theorist.

BW: Brian Greene is a string theorist, that's true. He uses strings to study cosmology, as many people do. There are other people who probably would refer to them like, okay, for example, I would call a lot of my work string theory and i did write some papers that were just straight up string theory. But a lot of it was stuff where I use string theory to study quantum field theories. So it's you know, am I a string theorist? I mean definitely not anymore now I'm a ninja (laughter) but you know even if I had kept doing what I was doing I probably would keep calling myself a string theorist despite the fact that a lot of my research has become more inspired by the toolbox of string theory than using "real string theory" itself. Some people might see this and say yeah, we told you it was crap see no one do, didn't do what it said. I think a more nuanced point of view is that people are now using this as a tool as part of a larger toolbox of things to study hard problems in physics. In some sense is that better than the original promise? No. Okay you know it'd be nice to have you know a theory of everything that explains the whole universe. But I think the problems that string theorists are facing today are still really interesting and a lot of progress is being made. So the thing I wanted to kind of correct the narrative of here was that string like the string wars are over, the people who said string theory was bullshit won. That's not the case at all. There's still lots of string theorists doing some really interesting research, who from the start viewed it as a tool to solve hard problems and that's what they continue to do.

S: So Brian, what this reminds me of, as like a non-expert, right? Just as a science enthusiast, is the Lorentz transformation, right, where Lorentz came up with a bunch of mathematical tricks, you know, to make the physics work, in terms of the like the math work, in terms of like the speed of light and things like that. And but he didn't believe it was actually describing the universe. And Einstein came along and said, no, that's actually describing how the universe works. That's why it's a useful mathematical trick, because the universe is mathematical and that's how it actually functions. So I'm getting the same kind of vibe from what you're saying, correct me if I'm wrong, if the fact that string theory, it may not be a coherent theory of everything, but the fact that it's a useful set of mathematical tools working out real problems in physics, does that, do you think that means that in, on some level it reflects some real aspect of the physical universe?

BW: Yeah I think, I think it does. Now I do, I do want to qualify that, is it being used to study real physical problems? I think that is still an open question, like a lot of these quantum field theories that are being studied with string theory are still theoretical models. So there's a lot of effort to try to understand real condensed matter models etc. with stringy inspired stuff. I don't know what the state of the art is on that but I think people have found it challenging to use these string models to really study like things you might see in a lab problems. So I don't think, it's not quite the same. The Lorentz, I mean the thing the amazing thing about the Lorentz transforms is that you know it was really, that's what led to the whole idea of relativity, right? Noticing that the equations of electricity and magnetism were invariant under this and they then hey what if all of physics wasn't variant under that? That's what led to relativity that is I think a much more, let's say, real world thing than what string theory is currently being used for. String theory is more used to understand the structures of quantum field theory, you know how scattering amplitudes work, stuff like that, that feels more, more generalized and less, for one of a better word "real". Now that's not to say it never, I do think to answer a question by the way, is I do think that, you know, I don't think it is all out of the question for stringy type physics to help explain real world problems. What those specific problems are is still an unknown.

S: Yeah.

BW: So I think there's some kind of stringy nature hidden there in the universe that we don't fully understand yet.

C: Can we change its name to "stringy type physics" because I like that better.

BW: Yeah. Well honestly that really is what people are doing these days. Like a lot of "string theorists" are just broadly speaking theoretical physicists who work on interesting problems that are, you know, it's at some intersection of quantum field theory, of mathematics, of condensed matte, you know. There are people who are like, who identify as string theorists, who work in a wide variety of things so stringy type physics is honestly a better description for what people are doing with it these days.

B: What about non-string specialists, are they embracing these new tools as well and steadfastly not calling themselves string theorists?

BW: Well you know, there's still a lot of hold over from people who don't believe that string theory is useful or or worth doing, I think especially among I don't know─

B: Old guard?

BW: ─it's kind of well, it's kind of generational but not really, it's more, it's almost more field-dependent. There's still there's still a bunch of people who think it's that it's just not worth doing. That to me seems ridiculous, I mean you can point to a million examples of, I mean probably the easiest ones are mathematical discoveries that came directly from people thinking about string theory models. So it's not like because some problems that are hard in math are easy in when you think about it in a string theory context. And then what people did, is they said oh here's the intuition from string theory, let me, that gives me an idea of what might be the answer, let me then go prove that. If that was all string theory ever did, that's amazing, I mean fields medals have been awarded for this kind of stuff. Like that, I don't understand how you can point to that and say oh string theory is crap. Like it literally.

B: Yeah it's on to something for sure.

BW: It has given us answers that we didn't previously know.

B: Right.

BW: And it doesn't just stop in math, it stops in, it continues in quantum field theory. And that's the other thing is I don't understand how you can point to a deeper understanding of quantum field theory and say oh who cares.

B: Right? That's pretty damn fundamental, hello.

BW: Yeah and that's yeah, that's one that I don't get, how could you yeah how could you say aaah.

S: Yeah and we've talked before about the fact that like even the question of is it true or not, it may not be the most important thing in science at this level. It's more of is it useful. And what was the quote like "shut up and calculate". Like don't worry about whether or not this is describing actual reality, just do the math. Does the math work? Great. You know that's, that's kind of that that's the level that we're at there.

BW: That's right, and it is an interesting question you know if, if you are complaining hey string theory is not rigorously defined. You know what, you're completely right, it is not rigorously defined but that doesn't mean that it's not useful. And you know, if there's one thing that distinguishes a theoretical physicist from a mathematician, it's not worrying so much about when things are rigorously defined, you know. Like you you start with kind of less rigor than a mathematician. Then you have to, you know, prove it, but not at the level of a mathematical proof. So you know you're allowed to throw out solutions for being unphysical, you know, they blow up at infinity or whatever. That's just kind of a normal part of doing theoretical physics. So I think it's okay to have a tool that is useful. And if you don't fully understand it.

S: Maybe an AI will understand it one day and they'll solve it for us.

B: Oh yeah, that's gonna happen.

S: That might, it might happen though, seriously like you know in 50 years you might have AIs who completely explain all this, and like humans never really understand it.

B: I mean sure, I'm sure there's things that we just cannot understand ever being a baseline human. It's like a dog trying to trying to understand algebra. Not going to happen, no matter how good of a teacher you are. And we may need to either augment ourselves or use an artificial intelligence to even be able to approach you know a decent understanding of some of this stuff.

Quickie with Bob (1:14:49)

S: All right Bob, give us a quickie.

B: Yes thank you Steve. Gird your loins people─

C: Ugh.