SGU Episode 398

| This episode needs: transcription, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 398 |

|---|

| 2nd March 2013 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

JR: Jon Ronson |

| Quote of the Week |

The world is much more interesting than any one discipline. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| SGU Podcast archive |

| Forum Discussion |

| This episode is in the middle of being transcribed by banjopine (talk) as of {{{date}}}. To help avoid duplication, please do not transcribe this episode while this message is displayed. |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, February 27, 2013 and this is your host Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella,

B: Hey, everybody.

S: Jay Novella,

J: Hey, guys.

S: and Evan Bernstein.

E: Ah. Kum bah wa, everyone.

B: Kum bah yay, what was that?

E: Kum bah ya, no. Kum bah wa. Japanese for good evening.

S: Good evening.

E: Lots of SGU listeners in Japan. We know a few.

S: So apparently Rebecca has some kind of phlegm situation going on.

E: I didn't know she was Amish.

S: We're trying to decide if she has the flu, whooping cough, or strep throat.

J: Well, get this, guys. So Rebecca emails us and says that she's not feeling well; that she woke up really late today, and she's been basically zonked all day. And at the same time, we have a little whooping cough scare going on over here with the newborn. This is what happened. My sister-in-law came to visit from Denver. And in the Midwest you know that the whooping cough incidences are higher and everything and I just didn't really think much of it other than everyone in the family got the tdap vaccination, which is the whooping cough

S: Did she and her family get the tdap?

J: Yeah, they did. What I found out today was that, like many of the vaccines that we get, you know they're guessing at which strain is gonna be the one that's gonna hit that year,

S: No, hang on a minute, Jay. What you're describing is relevant for the flu. With the whooping cough, it's not that there's like a different strain hitting every year, it's just that tdap covers only a very narrow number of strains and the virus has mutated. You know, it just, new strains are developing. But it's not like there's a seasonal strain like the flu. It's a little bit different.

J: Yeah, I didn't mean to confuse that. I know, like, exactly what you said, that there is a newer version of it that just wasn't covered by that particular vaccination that we got.

S: yeah.

J: So, her sister left on Monday morning. She called us up today, we're recording on Wednesday. She said "Guys, I had a bad cold on my way home, and now it's turning into something that's very, what I would consider to be whooping cough-like.

E: Yeesh.

J: So we called up our doctor, you know, I have a three-and-a-half-week-old in the house now, and you know, like, very dialed into this. And we called up the doctor up and me like "What's up? Like what do we do? What happens?" And pertussis is a bacteria, it's not a virus. So they have an anti-biotic for it.

E: Anti-biotic. Yeah.

J: So, what do you call it, Steve? Erythromycin?

S: Erythromycin, yeah.

J: Erythromycin, yeah. So that's the one that they use for it. And it's the mega-dose, like two pills the first day and then you take like this mega-dose thing for four days. Of course the baby's taking the liquid form and everything. But I'm sitting there tonight with my wife and we're giving the baby its first medication, and it's freakin' whooping cough medication! Like I wanted to strangle people. Thank you everybody for not . . .

S: Anyone who has never gotten vaccinated for whooping cough, yeah.

J: Something that we could

E: Way to blow the herd immunity; way to go.

J: We could get rid of it. Did you guys see the info-graphic of . . . the CDC puts out information every year, and somebody made an info-graphic of the incidence of morbidity before and after the vaccination for a particular disease came and went. Right?

S: Yeah.

J: And right out of the gate, things like smallpox and stuff, I don't remember the exact numbers, but we have certain diseases where there was like a half a million people dying a year, down to zero. After the vaccination. And there's like, in this info-graphic, I think there was more than a dozen of them. It was incredible. Like you see the numbers, how dramatically different they are. Right there. That's a hundred percent proof. They work. And yet people are walking around out there today and they don't care; that information is meaningless to them. How? Why?

B: Well what is the worst-case scenario with pertussis? I mean, how bad could it get?

J: It can kill you, Bob; it can kill a baby.

E: Death.

B: That's bad.

S: Yeah, there was that famous case in Australia where a baby caught, Dana McCaffery, caught whooping cough in a community that had very low vaccination rates because of the Australian anti-vaccination network preaching against vaccines, and, the baby caught it from unvaccinated people. And died. 'Cause the child was too young to be vaccinated. It's one of the populations that need to be protected by herd immunity.

This Day in Skepticism (4:33)

- March 2, 1983: Compact Disc players and discs are released for the first time in the United States and other markets. They had been available only in Japan before then.

S: Evan, so you're filling in for Rebecca this week for This Day in Skepticism.

E: I said "Good evening" in Japanese to start the show. And I did so because the compact disc, you guys remember what compact discs are, CDs,

S: They're still, they're still used today.

E: They are. Their first, most common usage was of course for music storage, right? Playing music. Put 80 minutes of uncompressed audio on one of those things. That's 737 megabytes of data. What do you think of that? So in Japan, is where the CDs were first, widely became available, in October of '82. However, on March 2nd of 1983, compact discs and their players were released for the first time in the United States and other markets around the world, whereas they'd only been available in Japan before but finally they came to the United States, and I remember this vividly. It was a big f'ing deal, for me and my 13-year-old friends and stuff who were all, in our own opinions, very big into music. And it was a rush to see who would get the first CD, who would be able to afford the first CD player. It was kind of bragging rights, in a sense. Do you guys remember?

S: Oh, yeah. Instantly replaced tapes, records; 8-tracks had already died by then.

E: Thank goodness.

S: Buy, yeah, and think about it, guys. Thirty years! And they're still a perfectly acceptable technology. I still buy CDs for music.

B: Really?

S: Sure.

B: Oh, man. I just download it all.

S: Yeah, but think about it. A CD, you can then rip it into any quality MP3 you want, which you own, without any DRM, and you have the CD for a backup. And it's still cost-effective. It's not like you're saving money by downloading. So it's still a perfectly viable technology. It's had a lot of longevity.

B: It's all right, I guess. I like, I hear a song that I like. Like, oh boy, that sounds really good. And I buy it. Within literally four minutes I have it on my iPhone and I'm listening to it. That's awesome.

S: I do that, too, but, if there's an album coming out and I know I want the whole album, I'll get it on a CD.

E: Something to remember, guys, is that when you purchase a CD, you're purchasing something physical that you actually own. And when you purchase a license to get a music or something you download through iTunes or something, there's a question, there's debates going on right now in the courts as to how much ownership do you actually have over that thing? In other words, can you put it into your estate and leave it to your heirs?

S: Right.

E: And they are fighting that. You know, the record industry, or industries, don't want those rights to be transferred on to descendents. Where, but with a CD you're guaranteed. That is yours, it's physical, you can do whatever the heck you want with it. So, keep that in mind also in the debate about, you know, what medium, what format you're gonna use for your music.

B: That's messed up.

News Items

Life Around Dying Stars (7:32)

http://phys.org/news/2013-02-future-evidence-extraterrestrial-life-dying.html#ajTabs

S: All right, well, Bob, talk about looking for life around dying stars.

B: If you insist.

S: I do.

B: So guys,

E: Like Mickey Rooney, are we talking? What are we talking here, dying stars?

B: Oh, boy. Guys, when you think of an extraterrestrial planet, especially one that supports life, what do you think of? Do you think of, you've got this planet orbiting a parent star that's kind of like our sun, right? Maybe it's a little bit bigger than our sun, maybe it's a little bit smaller. And of course, if that's the case, the habitable zone around the star changes because of how big and bright the star is.

S: Now, Bob, I think of Tatooine with two suns. (laughter)

E: Nice orchestral music playing.

S: Or Rigel 7 with a big planet in the distance with rings around it.

B: Yeah, but, still, it's like a, it's a real star, it's like a star that

S: Yeah, not a fake star.

B: It's fusing hydrogen into helium. No, but it's not a dead star, and that's the point here. There's a new theoretical study that finds that the most likely place possibly to find life on another planet may be around a dead star. More specifically, of course, a white dwarf. You know, I'm not talking about a neutron star or black hole. But not only that, they think they might be able to actually find one of these planets in the next ten years. Which seems like a pretty bold prediction.

E: But Bob, isn't a white dwarf after the star went through its initial sort of expansion then came back in on itself. Wouldn't it have kind of destroyed things on that

B: Well, exactly. And that's the huge problem. That's the first thing I thought of, well how can that be? A white dwarf is a dead star. It's a corpse of a sun-like star, at the end of its, you know in its old age it swells into a red giant and it totally crisps any of the planets that were nearby, but before it expels a lot of its mass, making the beautifully misnomered planetary nebula. So what's left is this collapsed core. It's about as big as the earth, but it's got the mass, it could have a mass of more than the sun. 1.4 solar masses, I think, is the ________________________ limit for that. So that's a lot of mass in a really tiny place. So clearly it's unbelievably dense, right? If you had a ton of white dwarf matter, if you could do that, you could fit it into a matchbox. I mean it's super, super tiny. You can thank the electron degeneracy pressure for that. But there's no nuclear reactions going on to produce energy, but because it's relatively small it could radiate it's remaining heat for literally billions of years. So clearly, then, this thing could have its own little Goldilocks zone to support life, even though it's really not even a star anymore. It's not creating energy, but it's just radiating away the energy that's contained in it for many, many, many eons. So then the next question then, Evan, which ties into your comment, was how does the planet get there, because the red giant's gonna wipe out anything that's nearby. Probably anything that's in the Goldilocks zone. So there's actually two ways that could happen. One might, you might predict, a planet can migrate in from the outskirts of a solar system; we've seen that with hot Jupiters: Jupiter-sized planets that have orbits closer than Mercury. How the hell did they get there? Well they can actually migrate in through the solar system. But there's another way. A planet can also form from the leftover dust and gas; and that, of course, would be a second-generation world, which I think is pretty cool. Now of course, though, this planet would have to get pretty damned close, since the heat source is so small and dim compared to regular living stars . . .

S: Bob, do we know that either of those can actually happen around a white dwarf, though?

B: The thing here, though, with this theoretical study, Steve, is that they ran these really sophisticated simulations and they've pretty much shown in the simulation everything that I'm talking about.

S: Okay. T B: That this can happen; they're incredibly confident that it could happen. They can think of no reason why it wouldn't happen. Now, it's not like every white dwarf is gonna have one these. They're saying that among the 500 closest white dwarves to the sun, they might find one or two that have planetary bodies in orbit around it that could support life. So, you know, one or two in 500 isn't great odds, but there's lots of stars and we can look at a lot of different things.

S: Yeah.

B: So, the interesting thing is, as you could imagine, these planets would have to be very close to the white dwarf in order to get enough heat to have liquid water and life evolve. So that turns out to be only about a million miles away, which is what one over ninety-three, wait, sorry. And that's, our orbit's 93 million miles, so it's way, way, way close to it. And it's year, of course, would only be about ten hours long, which is an amazingly fast orbit so that would, I cal . . .

E: That's a party every ten hours, oh my gosh.

B: I calculated Rebecca would be over 30,000 years old if she lived on that planet. (laughter) So, all right. So we've got this dead star that could conceivably keep a nearby planet warm enough for life, so we've got that. We've got a couple different ways for a planet to arrive or form nearby. So then the next interesting question is, how do we detect this thing? And, if you regularly listen to this show, I think you probably know: the transit method, right? A planet moves between us and their star. The output, the light output dips, and bam! You've detected a planet. Of course, it's a little bit more complicated than that, but that's essentially the idea. Now in this scenario it's actually even better. Now think of this system, though. You've got a planet real close to a white dwarf and the white dwarf is so tiny, I mean they could be comparable in size, so that when this planet eclipses the white dwarf, you're gonna have a huge dip in the light output. It would be an obvious signal. It would leap out and say "whoa!" This starlight almost completely disappeared.

S: But the plane of that system would have to be perfectly aligned with us.

B: Yes, it would have to be. But even if it wasn't, you could still occlude half the star or 33 percent, and that still would be really really good. That's not even the best part. The real icing on the cake for this is that the white dwarf emits so much less light it becomes much easier to determine the composition of the atmosphere of the planet in orbit around it. And it turns out that after the simulation I was talking about, they showed that after just a few hours of observation instead of something like hundreds of hours, we would know that the planet has perhaps water vapor or maybe oxygen in it. And oxygen would, that would be gargantuan news. That would be huge because, on earth anyway, oxygen is created by life. You take away life from the planet earth and it would slowly diminish, the oxygen would just disappear. It would dissolve into the oceans, it would oxidize the surface, and if we found a sizable amount of oxygen on a planet, I think it'd be pretty solid indication that there's probably some kind of life on the planet producing that oxygen. And if not, maybe it's some kind of alien machine that's creating and it wouldn't matter 'cause in that case we would find life anyway. So, either way, it's a win-win!

S: So now we've just gotta look for them.

B: Yeah, and the James Webb, the James Webb's a big thing, that once that guy comes online, that telescope comes online, I think, jees, I'm not sure when, but within a few years or so.

S: They plan on a 2018 launch date.

B: That is gonna have what it needs to really survey these white dwarves and find these planets and maybe find a planet that most likely has life on it. And how huge would that be; talk about the science story of the millennia, let alone the year!

S: Yeah, we'll probably cover that one.

B: Yeah, maybe. (laughter)

Ancient Lost Continent (15:06)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-21551149

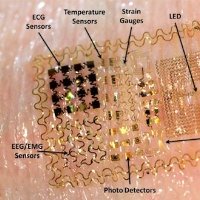

Electronic Tattoos (22:36)

Google Glass (31:25)

http://www.google.com/glass/start/what-it-does/

Who's That Noisy? (38:06)

- Answer to last week: Whistlepig

Questions and Emails

"Ow!" (40:36)

- Why do we say, "Ow!"? Joe Shoults

Interview with Jon Ronson (44:20)

- Interview with Jon Ronson, recorded at CSICon 2012.

Science or Fiction (1:00:50)

Item number one. Scientists have developed an imaging system that can look through walls into a burning building and identify survivors that need rescuing. Item number two. A new analysis finds that Spiderman’s webbing would have been strong enough to stop the commuter trains as depicted in the Spiderman 2 movie. And item number three. Researchers discover a virus with an adaptive immune system.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:13:44)

The world is much more interesting than any one discipline.

Edward Tufte

Announcements (1:15:27)

References

|