SGU Episode 378

This is a draft of the episode page skeleton, you can use it to structure your transcription page

| This is the transcript for the latest episode and it is not yet complete. Please help us complete it! Add a Transcribing template to the top of this episode before you start so that we don't duplicate your efforts. |

| This episode needs: transcription, proofreading, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 378 |

|---|

| 13th October 2012 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

RH: Robert Hutton |

| Quote of the Week |

The scientific man does not aim at an immediate result. He does not expect that his advanced ideas will be readily taken up. His work is like that of the planter — for the future. His duty is to lay the foundation for those who are to come, and point the way. He lives and labors and hopes. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| SGU Podcast archive |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Tuesday, October 9th, 2012, and this is your host Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella.

B: Hey everybody.

S: Rebecca Watson.

R: Hello everyone.

S: Jay Novella.

J: Hey guys.

S: And Evan Bernstein.

E: Hey, how are my teammates tonight?

J: Pretty good.

S: Pretty good.

J: What's up with you?

B: Pretty good.

J: What team are we on?

E: The Fighting Space Dinosaurs!

J: Oh, of course, of course!

This Day in Skepticism ()

- Fatima Miracle of the Sun - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_Miracle_of_Fatima

R: Hey, guess what today is?

E: Uhh...

R: Saturday, October 13th. Today... is the anniversary of the Miracle of the Sun, which was an event in 1917, when - in which tens of thousands of people claim to have seen the Virgin Mary appearing in the sun. This is something we've talked about before, it's known as the Lady of Fatima apparition. She supposedly appeared to three shepherd children, who - and told them that she was going to a reappear soon, and so they went and told everyone, and for some reason, tons of people believed them, and everybody went out and stared at the sun, until they saw the blessed Virgin Mary. So that was October 13th, 1917. On October 13th, 1930 the event was accepted as a miracle, and on October 13th, 1951, the papal legate Cardinal Tedeschini told a million people gathered at Fatima that on October 30th, 31st, November 1st, and November 8th, 1950, Pope Pius XII also witnessed the miracle of the sun, from the Vatican Gardens.

E: The only miracle is that not everyone went blind by staring into the sun.

R: Yeah, I mean ten minutes is a long time. Depends on how carefully they stared, how long they each stared.

B: How cloudy it was.

E: And I bet you some people cheated too as they realized, wow, this really, really hurts, they kind of, maybe, averted their eyes momentarily.

S: But, Joe Nickell says, Evan, they probably weren't looking at the sun, but at a sundog or a mirage of the sun, a mock sun.

E: Yeah.

B: Really?

S: So it wasn't really as bright as looking at the sun itself, just an atmospheric effect. And of course there are as many different reports about what people saw as there were people there. Some people saw nothing, some people saw rainbow hues, some people saw the, quote-unquote, "sun dancing around". So that's consistent with an optical illusion or an atmospheric effect, it was a subjective experience by the viewer, not something objective that everybody was seeing with a reasonable similarity of accounts, so... it's pretty clearly just, that's what you get when you stare at something really bright in the sky for a long time, you're gonna start seeing weird stuff.

J: But there was some pretty serious mass delusion or hallucination, what would you call it, Steve?

S: I don't know that that's the case, I mean, I don't know that you need to invoke a mass hallucination or mass delusion, more that just some people saw some atmospheric effects or illusion, and there was a shared belief, people were there because they were looking for a miracle, they were there to see a miracle, they were there because they shared a faith, and they saw something that they interpreted in line with their faith.

B: Yeah, Jay, don't forget expectation and desire can have a huge effect on what you perceive.

S: That's all you need.

B: Big big influence.

J: Sure, definitely, I mean I've read quite a bit about this... situation, I mean, what happened there, and there were reports of people saying that everybody was drenched from a downpour and then all their clothes dried in a matter of seconds, and there's a lot of statements being made about that, and I was just wondering, I mean, this didn't actually happen that long ago, wasn't - there are people that are still alive that were there, right?

S: So, it's getting close to a hundred years, right, it's 95 years ago, so, only little kids would still be alive.

R: So, no, probably not.

J: Yeah, actually, I've read about the - it was so long ago that there were people still alive. It's a sign of the age.

(laughter)

S: Right, so, yeah, there was nothing miraculous. The thing is, accounts like that, then you have rumour, and, you know, urban legend kind of effects taking over, where you get all kinds of weird reports about what happened. I always like to think of this in terms like we have these modern episodes where we're close enough to it where you could actually look at newspaper reports of different accounts of what happened that day. You can investigate it in a way that you can't investigate, for example, miracles attributed to Jesus of Nazareth in the New Testament, but, you could see how those kinds of stories would develop surrounding some kind of, just - the claim that there's something miraculous happening develops spontaneously, just imagine how superstitious farmers living 2000 years ago were.

J: Yeah.

News Items

Nobel Prizes 2012 ()

S: Well, we do have something serious to go onto: The Nobel Prizes for 2012!

E: (mock fanfare)

S: (laughter)

R: (feigning ignorance) I thought we talked about these last week, didn't we?

E: That was the Ignobel.

R: (understanding) Ohhh!

J: (laughter)

S: The Ignobels.

J: Thanks, Ev!

S: We're only going to have time to talk about two this week: the Nobel Prize in Physics and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. We'll do the Chemistry award next week. The Medicine one is interesting, you guys know who got this?

J: No.

S: Two guys, whose research was separated by 44 years. So that was very interesting.

B: Whoa!

S: So far apart. 1962, John Gurdon discovered that you can replace the nucleus of a frog embryo with the nucleus of a mature intestinal cell, and that new embryo could still develop into a normal tadpole. This was a stunning proof of concept which showed that contrary to common belief at the time, that even a fully mature and differentiated cell that had been dedicated to being just one type of cell like an intestinal cell, still had the capability of undifferentiating or de-differentiating back to an embryonic state and then turning into every kind of cell necessary to make a whole organism. It wasn't known if that would be possible or not, it was possible that once a cell had matured to a certain point it had forever gone down that path and not only deactivated genes but permanently turned them off in some way, or just that the process wasn't reversible. But what he showed, what Gurton showed, was that the process was completely 100% reversible, again, very stunning concept at the time.

E: What made him think it was reversible, or did he not have that expectation when he was doing - ?

S: I think he suspected that that was the case, that's why he did the experiment, but... his colleagues at the time were highly skeptical of the result, they didn't believe it at first, until it was replicated, so it was just like science is supposed to work. A new, really radically new idea, they said, "wait a minute, this doesn't make any sense, before we take it seriously, let's make sure it's reproducible". It was, and then changed our understanding of biology. 44 years later, and we actually talked about this news item in 2006, Shinya Yamanaka did a series of studies looking at the genetic mechanism of turning a mature cell into a pluripotent stem cell. So he took cells from a mouse, mature cells from a mouse, and by tweaking just four genes, was able to turn it into a pluripotent stem cell. Remember we talked about the fact that this was a total game-changer in terms of the stem cell controversy.

E: (agreeing) Mm-hm!

S: You no longer needed to harvest embryonic stem cells, you could just take skin cells or fibroblasts, turn them into stem cells that could then be used to become any other kind of cell that you want. And it was far simpler than we had assumed, we thought, must have been a really complicated process, but it actually turned out to be fairly manageable, only a few genes were necessary in order to make that process happen. That created the potential for a couple of things: one, make stem cells without having to harvest them from either fetuses or embryos, and two, the ability to take a mature person, someone who's 40's, 50's, 60's, you know, old, take a cell from them, turn it into a stem cell, and then, for example, grow body parts that are perfectly matched to them, grow a heart, a lung, a liver for example, whatever. Total game-changer, in terms of stem cell potential. You know, we're still in that early stage of practical applications, so these two guys who shared the Nobel Prize showed theoretically the potential of stem cells, but we still have - it's still a very difficult technology to implement.

S: The next is the Nobel Prize in Physics. This was given to two researchers, Serge Haroche and David Wineland, for independently inventing and developing methods for measuring and manipulating individual particles while preserving their quantum-mechanical nature. So, we do talk a lot about quantum mechanics on this show, mainly because it's so widely misunderstood and misapplied, it's the favorite go-to fake explanation for anything paranormal.

R: The Deepak effect.

S: Yeah, the Deepak - just make some hand-waving, "it's all quantum mechanics" -

E: Quantum, quantum!

S: One of the aspects of quantum mechanics is this notion of, at the quantum level, our particles can be in a state that is not fully determined, either a superposition of states or just in an indetermined state. However, when you make any attempt to look at or measure those states, by necessity you're interacting with them in some way, and that interaction collapses the indeterminacy into more of a classical defined state, so you can't see the quantum weirdness when you try to look at it.

B: It's decoherence.

S: Yeah, decoherence, it's collapsing of the waveform, whatever, you hear different terminology for that. So, that was a conundrum, in that you can't, you could never experimentally verify the quantum weirdness cause then, any time you try to look at, it's not there. So what these two guys realized is that you can look at it in subtle ways, maybe not full-on in the face, but you can kind of look at it out of the corner of your eye, you know, metaphorically you could interrogate these quantum systems in subtle ways without collapsing them or making the quantum weirdness go away. And interestingly they did it in complementary ways, coming at it from different angles. One of them looked at the quantum properties of light, by interacting it with atoms and electrons, and the other looked at quantum properties of protons, neutrons, and electrons, by interacting it with photons, with particles of light, so they've kind of done it in opposite ways, but they achieved the same end, able to experimentally verify this quantum indeterminacy by this more gentle or subtle way of looking at these systems without making the quantum effects go away entirely. So it did open up a completely new avenue of research in quantum mechanics.

J: Do you really think, though, Steve, that there's something to this, when I turn it over in my head, I'm seeing - the idea of superposition is that there really isn't a designated way to describe what position the quantum state is in, right? It's in all possible positions.

B: Guys, it's also important to note that this isn't just some theoretical thing that physicists think is happening, I mean they've actually done experiments where they can somehow show that it is in this superposition. It is actually in multiple state at the same exact time.

S: Well, Bob, let me play Devil's Advocate there for a minute, because just from a theoretical point of view...

B: How could you know that without interacting without interacting and collapsing the wavefunction.

S: Hang on. From a philosophical point of view, all of science is just creating an explanatory model that makes predictions, and we don't ever know if we're describing the way the world actually is, or we're just coming up with a way that we can understand, and think about the world in a way that makes predictions. The only thing we can really say about any kind of scientific theory is how well it makes predictions, not if it is the way nature really is, and I think that's true of all of our theories but it certainly applies to quantum mechanics, to some degree, the question is to what degree. We have a certain description of quantum behaviour, that predicts how quantum states are going to behave experimentally, and we make sense of that as best we can with our human brain, but we really have no way of knowing if it's describing how nature actually works, or just the closest approximation or model of it that we can come up with. I do have this suspicion, this strong suspicion, that our quantum-mechanical theories are missing something significant, and while they may be good predictive models of what we're going to see experimentally, that we're missing something conceptually fundamental about the world at that level, what's really going on. Maybe it's a limitation of the human brain, maybe it's just we haven't had somebody, the right combination of genius and opportunity and knowledge, for somebody to make that mental leap, essentially, the kind of leap that Einstein made with relativity, we're just waiting for that person to come around, the opportunity to come around, to really take us to a much deeper level in our understanding.

B: I don't know...

S: It's kind of an easy thing to say, to predict but... maybe it's just purely my bias, my uncomfortableness with the whole notion of quantum mechanics that makes me feel that that's probably the case.

B: It's funny you invoke Einstein, cause he, I think he felt similar to how you feel...

S: Yeah.

B: He couldn't buy that quantum mechanics was fundamental, and all the experiments and thinking since then, since he died, since even - since the 50's, 60's, and 70's point to the fact that it is fundamental, and any theory that transcends it would still need to have - wouldn't change really anything that we already know...

E: Has to encapsulate it, yeah.

B: ... about quantum mechanics. And so I think I would disagree a little bit from what you're saying, if you think that there is something much more fundamental about it.

S: Well, Bob, we're not disagreeing with each other necessarily, cause it could still be fundamental as a predictive model, but still, there'd be something deeper in terms of trying to conceptualize what's really going on. It's like classical mechanics and relativity, they were missing something fundamental, but their predictive models are still perfectly good...

B: Yeah, but...

S: They still work, in most situations, but there was something they weren't really describing what was happening in the universe...

B: I understand that. Yeah, one theory, what was the term... "subsumes" or...

S: Yeah.

B: One term - one concept subsumes the other, but the thing is though, the thinking with quantum mechanics is that, once that more fundamental foundation underneath quantum mechanics is found, then you would be able to explain things like entanglement and also you'd be able to explain things like superposition and the inherent randomness of quantum mechanics.

S: Yeah.

B: Cause as we know, quantum mechanics is fundamentally random, there is, you said "makes predictions", yeah, we can make predictions, but we can only predict, "well, there's a ten percent chance of this, and a thirty percent chance of that, that's the best we will probably ever get, and that's what rankled Einstein so much is that this inherent, this spookiness and this unpredictability, and I don't think we're necessarily ever going to get around that, even if we do find some other theory that can encapsulate it, I don't think we're necessarily going to get around that and if that's what your main concern about quantum mechanics is, my suggestion is, get used to it!

S: Yeah, well, here's my question, Bob...

E: Suck it up, in other words!

S: I acknowledge all that. Here's my question though, is... let's say we do get to some deeper level of understanding of quantum mechanics, is it going to make less sense or more sense at that point?

B: Haha!

S: Is it going to become even more mysterious and mind-boggling? Or is the light going to go off and go, "Ohhh, now it all makes sense now, I get it!" I don't know, I suspect it'll become even more weird.

B: I think, yeah, I think the former, and I think this is one of the examples of things like trying to teach a dog calculus, it's just, you're never going to do it. I just think we've reached a wall, where we'll never be able to wrap our head around, not only quantum mechanics, but anything more fundamental...

S: Right.

B: ... I think would just be forever beyond our grasp. Until of course we uplift our brains and then we can have our aha moment!

E: Yeah, what about turning a computer like Watson loose on the problem, you know?

B: Well, yeah, I think an artificial intelligence will probably be the first conscious entity to perhaps understand that.

S: We have to program into them a deep and abiding desire to explain their knowledge to us...

B: Yeah, that's right.

E: And to not kill us in the process.

S: Right. (laughs)

E: Please!

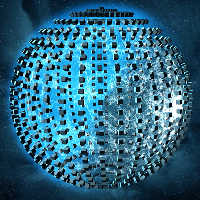

Looking for Dyson Spheres ()

S: All right, let's move on. Bob, you're going to tell us about how to find alien civilizations.

B: Yeah, so Penn State astronomers have recently been given a grant for a two-year search for signals from extraterrestrials. That doesn't sound too unusual, but they're not looking for radio waves though, they're looking for the telltale signals of a power source used by supercivilizations, namely Dyson spheres, used to capture all or much of a star's entire energy output. These are three Penn State astronomers that are led by Jason Wright, and they're using grant money from the John Templeton Foundation's New Frontiers program, which is designed to answer fundamental questions about existence and the universe. And the scientists are using NASA's Wide Field Infrared Surveys, or WISE, satellite to look for these telltale infrared signatures from Dyson spheres.

S: Now, Bob, before we move on, I do want to mention that generally I'm not a big fan of the Templeton Foundation...

B: Yes, I agree!

S: Because they support a lot of muddling of science and spirituality...

R: Chopra-esque.

S: Yeah, by "big questions", they're not talking about necessarily big scientific questions, so much as big spiritual questions about what does it all mean. They fund a lot of nonsense...

B: Yeah, and also trying to join faith and science.

S: Yeah.

B: Which I think is a mistake. And I absolutely agree, Steve, and I even hesitated mentioning them in my talk.

S: No, it's good! This is the-

B: That's how I feel about that...

R: It's good to know.

S: It's good to know, this is the only thing they've funded that I think was worthwhile, that I personally know of.

B: Absolutely.

R: And it's interesting timing too, because Templeton was set up as a response to the Nobel Prize, as a way to do the Nobel Prize for religion basically, and it's always - one of the rules is that the prize has to be greater than the Nobel Prize.

E: One-up.

R: Yeah, it's basically designed to one-up the Nobel.

B: Well, these objects, these Dyson spheres were hypothesized by mathematician and physicist Freeman Dyson in 1960. Now, one common conception of these things sees them as solid spheres of material surrounding a star at, say, planetary distances, like say 1 AU, 93 million miles, which is the distance from the Earth to our Sun.

E: Average.

B: And their purpose is to absorb the entire energy output of the star for use by whoever, the civilization, the engineers that created it. And this is of course engineering at a scale that we can't even possibly imagine pulling off. What we're talking about here though is astronomical-scale engineering or simply astro-engineering, which is engineering at a scale that is just mind-boggling. Now Dyson's train of thought kind of went like this: he was thinking, all right, energy consumption of a technological race can increase at a pace that would eventually - the planet itself could no longer supply what was needed. Just looking at our energy needs - our energy needs have doubled in the past 30 years. If you just extrapolate that, then our needs will outstrip what the Earth can supply in just four centuries, and I think that will be even a lot sooner than that. So he believed that one of the only options available to these civilizations included harnessing the parent star's energy. This is of course a titanic amount of energy; the amount of energy that intersects with the Earth from the Sun alone is about ten thousand times the amount that our industrialized nations currently utilize. So the idea of this solid shell of matter, though, photovoltaics or whatever analog they have in their civilization, is not really tenable. It couldn't really be pulled off for multiple reasons, one of them being the fact that you can't really keep the shell stable in orbit, and to orbit around the Sun, eventually it would destabilize and collide with the Sun, and there's just lots of problems with actually a solid shell around the star. But interestingly, though, there's enough matter in our solar system to construct something like that, so if we ever wanted to do it, there is actually enough matter to do that, depending of course how thick you make it. So in reality, civilizations would probably create something better described as a Dyson swarm, which is a huge discrete orbiting solar collectors that could be built incrementally over time, and absorb, of course less energy than a sphere but there'd still be plenty of energy, even for beings like the Organians, the Q, or even the mice that run the planet Earth. So, if - (indignant) come on, give me a chuckle!

(fake laughter)

B: Jesus!

R: We all got the reference, so you don't need to...

E: Star Trek.

B: Just fake it. Fake it, kids. So if Dyson is correct and a decent number of super-advanced alien societies have created these Dyson swarms to power their iPhone Five Millions or whatever, their ultra-high-def yottaflop universe simulations, then they should be detectable by us, and by the infrared - the heat that is emitted by this sphere or swarm. And I think this is a great idea because if we assume that these incredibly advanced civilizations exist, then certain types of astro-engineering that they would do would by their very nature be detectable by us. And I think this is one great example. But where this idea falls down a bit though, however, is the premise that the Dyson swarm creation is very likely. Everything I read made it seem like it, Dyson believed that this is almost an inevitable occurrence, once you reach this milestone where you need more energy than your local environment can provide, he kind of made it seem like, yeah, it's almost inevitable, and I just don't share that high degree of confidence, I think there might be lots of different ways that these super-high-tech societies can get their energy. I tried to do some research on what some of these were. I came across a couple good ones: perhaps they can capture the energy from gamma-ray bursts. Now I don't know...

J: Wow!

B: ...How much energy - Yeah, I mean there's a lot of energy from gamma-ray bursts out there, but I don't know how feasible that is, to power your society from them, but it's just an idea.

J: Yeah, how do you predict when one's going to happen?

B: All you really know, Jay, is the frequency, so many bursts will occur in this area of space over this certain amount of time. Another option would be that they could feed stars into black holes and then live off the energy that's emitted by the accretion disk that swirling around the black holes.

R: Harsh!

B: Or maybe these civilizations are just jacked into their own private universe, and they don't really need that much energy, just plug in the computer and live your life in whatever universe you want to live in, they just don't need that much energy. Then there's also this other idea that, what if the civilization doesn't want to be detected. They could possibly cloak the infrared emission from their Dyson sphere or swarm, so that nobody else can find them. And this is actually feasible; they could come up with some clever way to get rid of the waste heat that's generated by the swarm, that's possible.

S: Yeah, I was thinking about that, maybe, wouldn't they be so super-efficient that they would just be using that infrared part of the spectrum rather than having it be waste heat that we could detect?

B: Yeah, but think about it though, they're getting so much energy from their sun, and they've got this very low energy, very hard to use waste heat, they could just let that go and not even worry about it. Why would you care about a quadrillionth of a percent of the energy that you're getting just cause it's wasted away in heat, "Oh, we've got to capture that little bit too!" You know, I think they could safely ignore it unless they're really dedicated to privacy and they don't want to be found, and there's ways to deal with that. One way would be to build a Dyson swarm that's a hundred times bigger than necessary. If you build one big enough, which would be huge, say about twice the distance of Pluto when it's at its farthest in its orbit around the Sun, we're talking - could you imagine a swarm of photovoltaics twice the distance of Pluto? That's just mind-boggling. But the idea though is that if you have it that big, then the waste heat that would eminate from the shell or whatever you're using would be so cool that it would be indistinguishable from the cosmic microwave background radiation, and then their existence would get lost in the noise of the universe, and they would be essentially undetectable. So that's just one way that they could feasibly deal with it, and I would think that if civilizations are doing this, then I don't think they're going to care too much, but who knows what's with their thinking? But it doesn't matter to me though, I think this is a great idea even though these little problems that could crop up. In some ways I think detecting a Dyson swarm is a lot cooler than a boring radio signal. To me it's just so much more awe-inspiring to imagine that we detected aliens, not because they were sitting in some super-radio antenna, pinging the universe with hellos, but because they had the audacity and the skill and the need to build something on the scale of the Sun, which is just amazing to me, and I'd love to find evidence of that.

Simon Singh and Libel ()

Presidential Lie Detector ()

Who's That Noisy? ()

- Answer to last week: Magnetosphere

Questions and Emails

Proof of Heaven ()

I discovered your podcast a few months ago and I'm currently working through the back catalogue so I don't know if you've discussed this recently or not. Here's a link to a story about a neuroscientist who spent time in a coma and claims "as far as I know, no one before me has ever traveled to this dimension (a) while their cortex was completely shut down, and (b) while their body was under minute medical observation, as mine was for the full seven days of my coma." I am completely sceptical of his claims, but I'm no scientist so I was wondering about Dr Novella's opinion on what the brain might do if the cortex is shut down and how this could possibly be explained. http://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/a/-/breaking/15068392/top-neurosurgeon-spent-six-days-in-heaven-during-a-coma/ I also just wanted to thank you all so much for the work you do. I'm always trying to improve my thinking through reading and informing myself about all kinds of different topics, but listening to all of you has helped me understand how vital sceptical and critical thinking is. Your podcast has helped me improve my thinking processes immeasurably and I am so grateful for it, can't get enough. I am studying to become a primary school teacher, and I now vow that if there is one thing every student will leave my class with at the end of the year is a basic concept of critical thinking skills! So there you go, knock on effect :) The world needs more people like you guys. Much love and good will, Tessa French Sydney, Australia

Interview with Robert Hutton (54:23)

Steve: joining us now is Rob Hutton who is the head of the SGU transcription project. Rob, we thank you for all the hard work that you're doing and you're here to tell us about your effort to transcribe all of the SGU and that you need help---not surprisingly.

Rob: yeah.

Jay: heh.

Rob: That's right I mean it's a pretty gargantuan effort, you guys've been pretty prolific over the years.

Rebecca: sorry about that.

Evan: yeah, right?

Bob: ha ha.

Rob: how inconsiderate.

Bob: I tried to make 'em stop but they won't listen to me.

Steve: so tell us about it.

Rob: well uh you know I was got addicted to the SGU as a lot of people seem to be, and uh I was sort of wondering what I could do to help, it's uh kind of changed the way I thought about the world, so, I wanted to give something back, and being a systems administrator, working with computers every day, so I thought some transcripts would be really good, so I decided to set up a wiki page and it's kinda taken off, actually.

Jay: so what's what's been happening? you say taken off---what do you mean?

Rob: well, we've got 35 of the 377 SGU episodes done and 21 of the 5x5 episodes and we've had, you know, a couple of really dedicated contributors; we've had Mike C and Kat Grafton(?) and who've I mean Kat's had her brother who's an amazing artist doing all sorts of icons and and things for the site so it's really starting to look good and really starting to come together you know we're starting to get some search hits and I think it's turning into something that'd be quite useful but it'd be great if we could have more people chipping in making it a bigger resource.

Rebecca: and are you able to do a transcript in less than a week so like are you keeping up at this point?

Rob: we were keeping up initially I think we're sort of falling behind a little bit so you know any help we could have would be great. What we're doing at the moment is as soon as an episode comes out we put the skeleton of the episode on the site and we break it up into pieces, we put timestamps in each piece and the we encourage people to just take one chunk and do one chunk.

Jay: So Rob, what could someone listening to the show do to help?

Rob: there's a lot of things. Just come inside and have a look at the help text we put together on how to do a transcription it's a good start. It's quite easy you just download an audio player and play back the audio at a slower rate so you can type it out at that speed [bob mumbles] then you just copy paste the text you transcribed into the wiki software. It's quite easy to do [...].

But even something like proofreading which you know once somebody does a transcript if you can proofread it, you can do that almost at full speed doesn't take much time, each thing needs to be proofread, 'cause you often don't get it perfectly the first time.

Jay: How do you make it so that people don't do the same episode?

Rob: When you're starting to transcribe something, there's a little template you can copy-paste it's just one word surrounded by squiggly brackets, and that puts a little marker into the page saying "I'm working on this section; nobody else work on it".

Jay: Oh ok.

Bob: Rob, I need to ask which voices are the hardest to distinguish; it's Evan and Rebecca, isn't it?

[laughter] [...]

Rob: Yeah that's right.

Evan: We sound so much alike.

Bob: I knew it.

Rob: Jay and Bob are the hardest to tell apart; I've never personally had a problem telling you guys apart.

A lot of people complain about Jay and Bob sounding the same.

Jay: Jay, that's funny, isn't it? ;-)

Bob: It sure is, Bob, you futz :D

Jay and Evan laugh.

Jay: Try to transcribe that! :P

Bob laughs.

Jay: I like the idea of being able to... first turning the episode into text is great, 'cause you can search for something if they heard something on this show or they don't remember which show it was on...

Rob: even accessibility, there's a whole community out there that's hard of hearing or whatever and that adds them in, but even absolutely being able to link to something you heard on the SGU; to be able to send just that section to a person that's particularly interested in that would be really powerful, and even to back up arguments you've been having at the pub.

Jay laughs.

Steve: this is definitely a wiki crowdsourcing project kinda'---a bunch of people doing a little bit rather than a few people killing themselves, so... I like the way you break it up so people can can come in easily contribute as little or as much as they want and the whole project will take shape from there.

Jay: yeah, Rob, say somebdy wants to just do a science or fiction, or whatever, is that OK, is it too small?

Rob: no that's great, anything they can do is perfect and really helps.

We even got some fun sections in there.

We got a section for people's favorite quotes.

Bob: oh cool.

Rob: there's not a lot up there yet but I'm sure that a lot of people [... ?].

Jay: Rob, where should people go, where's the address how would you like them to contact you, or what's the process?

Rob: so if they just go to sgutranscripts.org the wiki's right there, they can sign up.

Unfortunately we've made it registration only at the moment ... that just sends us an email and we tick off the account and once they've got their account they can contribute as much as they want.

If there's any problems with that they can contact us at info@sgutranscripts.org.

Jay: and when people do the transcripts do their names get added to a list of contributors.

Rob: yeah the wiki software provides that all automatically so you can even see who the top contributors are and so forth, there's a list of that on the special pages.

Jay: yeah, why don't we set up the first goal: the first person to join the site to do five episodes on their own---and you confirm it, Rob---we'll give them any t-shirt they want.

Rob: all right.

Steve: any sgu t-shirt.

Jay: any sgu t-shirt.

Evan: should be qualified, yes...

Jay: I want the t-shirt Brad Pitt was wearing.

Bob: yeah.

Jay: Rob, let us know when it happens and then we'll set up another milestone.

Steve: all right, Rob thanks for all of your work, took a little initiative, found a way to contribute to the overall

Rebecca: yeah, thanks so much

Rob: thanks you guys for the podcast, it's been great

Jay: thanks, Rob.

Science or Fiction (1:00:36)

Segment: Science or Fiction [ Click Here to Show the Answers ] Item #1 A newly published paper claims to have found the true solution to the pioneer anomaly (the tiny excessive deceleration of the pioneer probe) in the laws of physics. http://munews.missouri.edu/news-releases/2012/1009-interstellar-travelers-of-the-future-may-be-helped-by-mu-physicist%E2%80%99s-calculations/ Item #2 Chemists have developed a pencil that can draw functional sensors on a piece of paper. http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2012/drawing-with-a-carbon-nanotube-pencil-1009.html Item #3 Researchers have developed a method of producing black silicon, which can be used to make semiconductor processors several thousand times faster than silicon-based processors. http://www.fraunhofer.de/en/press/research-news/2012/october/solar-cells-made-from-black-silicon.html

Skeptical Quote of the Week ()

The scientific man does not aim at an immediate result. He does not expect that his advanced ideas will be readily taken up. His work is like that of the planter — for the future. His duty is to lay the foundation for those who are to come, and point the way. He lives and labors and hopes.

J: Nikola Tesla!

Announcements ()

References

|