SGU Episode 438

| This episode needs: transcription, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 438 |

|---|

| December 7th 2013 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guests |

TF: Tim Farley |

SG: Susan Gerbig |

| Quote of the Week |

The real advantage which truth has, consists in this, that when an opinion is true, it may be extinguished once, twice, or many times, but in the course of ages there will generally be found persons to rediscover it, until some one of its reappearances falls on a time when from favourable circumstances it escapes persecution until it has made such head as to withstand all subsequent attempts to suppress it. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

This Day in Skepticism (00:36)

- December 7: Happy birthday to psychologist Eleanor Gibson and deathday to Rube Goldberg.

News Items ()

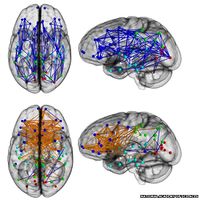

Male-Female Brain Wiring (04:27)

Wormholes and Black Holes (21:31)

Home Genetic Testing (29:14)

Who's That Noisy (39:46)

- Answer to last week: Bjorn Lomborg

Interview with Tim Farley and Susan Gerbic (44:08)

- Tim Farley is a Research Fellow for the James Randi Educational Foundation. He's the creator of the website whatstheharm.net and blogs about internet techniques for skeptics at skeptools.com.Affectionately called the Wikipediatrician, Susan Gerbic is the co-founder of Monterey County Skeptics, a member of the Independent Investigation Group (IIG), and a self-proclaimed skeptical junkie. Susan is also founder of the 'Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia' project and the 'World Wikipedia' project.

Science or Fiction (1:04:21)

S: Each week I come up with three science news items or facts, two genuine and one fictitious, then I challenge my panel of skeptics to tell me which one is the fake. We have a theme this week—

E: Duh duh duh!

S: The theme is "how many?" and we have four items.

R: How many?

S: There are four items. OK. Here they are: The human body has more than 12 distinct types of sensation (without dividing taste, smell, vision, or hearing into subtypes). Item #2: There are six known moons of Pluto (five named), and 83 confirmed moons of Jupiter. Item #3: There are 11 known states of matter (not counting non-classical states and purely theoretical states). And Item #4: There are currently six people in space. So obviously, this is all about the numbers; one of those numbers is incorrect.

J: Uh, I'm not a fan of this!

S: Jay, go first.

E: (laughs)

J: OK. So, this first one. I do believe that there are other types of sensations other than the five obvious senses that we have. And I'm not dipping into "sense hunger" or any of that nonsense that L. Ron Hubbard wants us to believe. And the second one here, that there are six known moons of Pluto... oh, wow; I just—I don't even know if Pluto has any moons. That's how bad this one is. You're supposed to know stuff like that, Bob, and I'm supposed to know about yelling and bad accents.

B: (chuckles)

E: And Thanksgiving.[1]

J: Thank you. Yeah, and where was my Thanksgiving Science or Fiction, Steve? Really, really...

R: It's true.

J: You did me wrong, son. I'm not sure about the Pluto one, and I just hate having to admit to myself that I don't know more information about that. And the final one that are 11 known states of matter. Damn you! I believe there are six people in space right now, so that's the fourth one; I'm going to say that's science. Between two and three, I'm going to say that there are not 11 states of matter.

S: OK. Evan?

E: Um, for the 12 distinct types of sensation in the human body, that really doesn't make sense to me. Certainly not what we're taught in school, but that doesn't mean a damn thing these days. I'm having a problem with this one: "distinct types". I don't know that they're distinct; lot of things are connected. Six known moons of Pluto, five named, 83 confirmed moons of Jupiter? That's a lot. Always thought Jupiter was kind of in the 40s or 50s, but they're always finding new moons. I would not be surprised. Eleven known states of matter. Well, sure, I'm tending to think that that one is correct. You know, please don't ask me to name them (chuckles) because I couldn't get all eleven, I think, in under the worst of circumstances. And then this last one. There are currently six people in space. You know, what can you say about that? There either is or there isn't. And you kind of just have to take a guess with that one. So it's coming down to the six people in space or 12 distinct types of sensation. Given those two options that I've narrowed it down to, I'm going to have to say that the 12 distinct types of sensation I'll say is the fiction.

S: OK. Rebecca?

R: Oh, man. That was the one that I thought was science, 'cause... I don't know about 12, but I know that there are other senses like sense of balance I know is one that people don't ordinarily think of. And there must be more; like, I feel like psychologists are always coming up with new senses. Like, what about the sense that you're an individual? You know, there are people who have brain damage who lose certain senses about themselves and it's really freaky. So I don't know; I feel like that one could be true. Six known moons of Pluto, 83 moons of Jupiter; no idea. Honestly, I have no idea. Eleven known states of matter? I mean, I know the solid, liquid, gas, plasma. That's four. What else could there be? I don't know. Do Newtonian liquids—is that a... I don't think so. I don't—there's probably—I'm sure that there must be some other crazy states of matter that I don't know about, but... I don't know. And I have no idea how many people are in space at any one time. How do we even define space? We can't, Steve.

E: (laughs)

R: Somebody just went into space and came back just now while I was answering this question, so I don't know. I don't know; I guess I'm going to go with the states of matter one, because I feel like eleven is too many states of matter, but I'm probably way wrong.

S: OK. Bob.

B: Yeah, this is tough. These numbers are good; they're just outside of the range that I'm comfortable in. Yeah, for distinct sensations, I kind of like what Evan was saying about how twelve distinct ones definitely seems high. A lot of them are just kind of fusion of different sensations. The moons of Pluto... I wasn't aware of the sixth one, and 83 for Jupiter? Yeah, I just lost count. And that seems a little high, but not that high. The eleven known states of matter. That seems high as well; I mean, there's a bunch of them besides the obvious: plasma, Bose-Einstein condensate; there's these quasi-crystals...

R: (laughs) Were those part of the obvious?

E: Course Bob knows.

B: Quark-gluon plasma...

R: You know, the obvious ones: The Bose-Einstein crystallites.

E: He was reading a paper on that earlier today.

B: No. I said beside the obvious solid, liquid, gas.

R: Oh, OK.

B: But even for those, I remember thinking, "that's it; I've just officially lost track of how many states of matter there are." There are just all these obscure ones. Some of them are fascinating; other ones were kind of not as fascinating. But that still seems high to me. And people in space; I really don't know; six sounds reasonable. Part of me is thinking that that's such a simple little thing. There are six people in space, and that's going to be the fiction; nobody's going to pick it.

E: (laughs)

B: Jay, what did you pick?

J: I said that the eleven known states of matter.

B: Screw it. I'm going with the six people in space.

E: Right, Bob. Good for you.

S: OK. All right. So, the one that you all agree on is that there are six known moons of Pluto (five named) and 83 confirmed moons of Jupiter. You all think that is science.

E: Gosh.

B: Wait! Can I change my mind??

(laughter)

S: No.

B: I know; I know.

S: And that one is... the fiction!

E: Of course it is! Because—

R: (groans)

B: F[deleted] you, Steve!

S: Because... there are five moons of Pluto; Bob, we have not discovered a sixth.

E: Right!

R: Come on!

S: Those moons are—you should know how many moons Pluto has!

J: There are no moons of Pluto!

R: Why??

S: Charon—

E: We talked about it; Nix and... the other one.

S: Yeah, Nix and—we just talked about this![link needed]

R: Why do I ever need to know about that?

S: Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberus and Hydra.

E: Cerberus; right.

S: And Jupiter has 67 confirmed moons, not 83.

J: There's a lot of people listening to this show right now that were in the same exact shoes as I was in. Admit it, people—

E: I was right about Jupiter!

J: A lot of you should know. There's no—nobody knew that there were any moons of Jupiter. There were no moons of Jupiter before the recording of this program.

S: Jupiter? You mean Pluto.

J: Whatever!

E: Same deal.

S: Jupiter has 67 moons. All right. Let's go back over the other ones in order. The human body has more than 12 distinct types of sensation (without dividing taste, smell, vision, or hearing). That is science. I had to say "more than 12" because there's just no way to give one number. It depends on how you divide them or count them. I said "not dividing taste" because do you count bitter, salt and sweet as three sensations or one?

R: No. What are you, crazy?

S: Is color and black-and-white vision could be more than one. Every smell; how many different types of receptors do we have for smell? So I said, "just forget those; we'll keep those as just one type of sensation". But in addition to sight, smell, sound and taste, we have temperature, pain, Propioception, soft touch, pressure, vibration, vestibular sensation, itch and stretch. Like, you know when your bladder's full or if your bowel is distended.

B: Isn't itch just a form of pain?

S: That's thirteen—nope; there's a distinct receptor for it. That's thirteen; I got over 12, so I just said "more than 12". If there's more, whatever.

E: (laughs)

J: I knew it; I was right. Thank you.

E: Bastard.

S: Yeah, they actually discovered that there's—and they're distinct; they have distinct receptors, pathways—

J: Steve! I got one that you did think of: Detect fart.

S: Detect fart?

J: No, because you know they're different—

R: I believe that's pressure.

S: That's a combination of stretch and odor.

J: You know—there's a difference. You know whether you have to go to the bathroom or you have to fart. Or else we'd all be shitting our pants!

R: Well, hopefully you do. Sometimes people—

S: We'll call that the Jay Principle.

B: Not always.

J: No, I've named it "Detect Fart". Thank you.

S: (chuckles) Isn't that a Scientology power?

B: (chuckles) Yeah, right.

S: All right. There are eleven known states of matter (not counting non-classical states and purely theoretical states). So, I had to throw that caveat in there because there's all sorts of possible states of matter and I'm sure somebody could come in and say, "no, there's only eleven—there's only ten" or there's twelve or whatever. But here are the eleven. I tried to... You gotta draw the line somewhere between how much confirmation's enough to say we know that it exists.

B: Right.

S: But here's are the eleven I thought were above the board: Solid, liquid, gas, plasma—you all know about that—superfluid, Bose-Einstein condensate, fermionic condensate, Rydberg molecule, photonic matter, degenerate matter and quark-gluon plasma.

B: What about a quasi-crystal?

S: Those are non-classical states.

E: What about dark matter?

S: Dark matter's purely theoretical.

E: Uggghhh. What? Wait a minute! What do you mean, "purely theoretical"?

S: We don't know what it is. It's just theorized that it must exist.

E: But we know it exists!

S: There was like, ten other ones that probably, that theoretically should exist; we have no idea what it is. I didn't count those.

B: That's awesome. Read those again!

S: But the list could be a lot more; I mean, there's a lot more things potentially on the list.

E: Bob's getting excited.

R: Go Google it and read it yourself.

S: Solid, liquid, gas, plasma, superfluid, Bose-Einstein condensate, fermionic condensate, Rydberg molecule, photonic matter, which we talked about recently; degenerate matter, like in a neutron star and quark-gluon plasma. Quark-gluon plasma's on the fence about because—

B: Why?!

S: Because how confirmed is it? We've definitely detected it in particle accelerators, but it's not 100%, 100% confirmed. I thought it was above the bar.

B: Oh, come on. Yeah, it is.

R: I think my cat is a new state of matter, because he is soft and squishy; I can touch him, but he also seems—so that's like a solid, but he also seems to fill any space, like a gas. So like a very tiny box or a very large box; he can fill it perfectly.

J: And Rebecca, that's another sense: Detect cat.

R: Yes.

S: And, there are currently six people in space. They are: Oleg Kotov, Mike Hopkins, and Sergey Ryazanskiy; they've all been in space for 70 days. Rick Mastracchio, Mikhail Tyurin and Koichi Wakata have been in space for 28 days.

E: Hey, Koichi. He listens to the show.

J: So how many people are in space right now?

S: There's two Americans, three Russians and one Japanese.

B: Hey, I heard Koichi went home, so I think I win.

S: What do you mean? How could he have gone home?

R: He was homesick.

B: He was tired of it.

R: Had his parents pick him up.

E: No, no, he just did what Sandra Bullock did in Gravity.

S: There's a website called, "howmanypeopleareinspacerightnow.com".

R: Really?

(laughter)

B: Oh, awesome! Awesome!

S: Yup.

B: That's great.

E: What is it, just one big number six on the screen? (laughs)

S: (laughs) Yes, exactly! There's a picture of the Earth; there's a big number six on the screen. And then below that are the names. But yes, that's it!

R: Wow.

J: That is awesome.

B: What's the highest that number's ever been, I wonder?

S: I don't know.

E: Oh, gosh.

B: I should know.

R: Is there a website, "whatsthemostpeoplewhohaveeverbeeninspace.com"?

S: (laughs) We need to make one.

B: Steve!

S: Yeah?

B: Did you say, "Rydberg atom"?

S: Molecule.

B: How did they—so they classify that as a separate state of matter?

S: Rydberg molecule. They did; yeah.

B: That's interesting; OK. 'Cause isn't that where the molecule is—the electron is so far away that it actually exhibits classical and quantum characteristics?

S: I believe so; yes. I could read the description for you.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:17:18)

'The real advantage which truth has, consists in this, that when an opinion is true, it may be extinguished once, twice, or many times, but in the course of ages there will generally be found persons to rediscover it, until some one of its reappearances falls on a time when from favourable circumstances it escapes persecution until it has made such head as to withstand all subsequent attempts to suppress it.'-John Stuart Mill

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References

|