SGU Episode 997

| This episode needs: proofreading, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 997 |

|---|

| August 17th 2024 |

|

Exploring the International Space Station: A hub of innovation and collaboration in space. |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

"It is important to promote a scientific attitude. This is much more important than really understanding all concepts about science. If you understand how science works and you develop a scientific attitude towards the world, you are going to be a skeptic." |

Natalia Pasternak - microbiologist, author, and science communicator |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| SGU Forum |

Intro

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Tuesday, August 13th, 2024, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening everyone.

S: We're recording a day early because we are going to Chicago this weekend to do the extravaganza and to record the 1,000th episode. So when this show goes out there, that will be extravaganza day, and the day after the show goes out, we'll be recording the 1,000th episode. So it's probably too late to get tickets.

E: Yeah. But try.

S: So Jay, today is International Left Handedness Day.

J: Yeah.

S: And you're left-handed.

J: So what am I supposed to do? Let's really think about this. How do I celebrate my left-handedness? What am I supposed to do?

C: You're supposed to...

B: Give it a day off.

E: The rest of us are right-handed. We have no idea how you think.

C: Go to the left-handed store, buy a bunch of left-handed items.

E: That's right. Drive on the left side of the road suddenly.

J: I kind of like being left-handed.

S: Really? Why?

J: I don't know.

C: Jay, I say this not to make you feel uncomfortable, because this is, you are like my brother, so this is separate to you. I am weirdly attracted to left-handed people.

S: Really? I agree with you, that is weird.

C: Has anybody else-

E: You noticed that?

C: Yes, I've noticed that I think I date a higher than normal proportion of lefties.

E: You're sure you're not just-

J: That's intersting Cara.

C: I'm just wondering what other traits come along with being so...

E: Sinister?

C: Sinister, yes.

S: I didn't mean to kink shame you there, Cara.

C: Thank you.

S: No, what's funny is that that was an answer in a recent New York Times crossword puzzle.

C: ink-shame.

S: I know. Kink-shame. And my wife had never heard the word before and she doubted it was real until I was proven correct when we finished the puzzle.

C: That's funny. We got that one right away.

E: And then-

J: What I'm not sure about is why would some people decide like, hey, we're going to push to have like a national-international left-handed day, like, I wasn't like teased or anything, so I don't need like the support aspect of it. I just don't get it.

C: Maybe people were back in the day a lot more. I mean, a lot of people were forced to be right-handed.

S: I don't remember ever being a thing. I think when we were young, we were already past the anti-left-handed phase. I remember when we were young, talking about, oh, in the past, people would force you to write right-handed and whatever, but that was already done.

C: But to be fair, even though in the past you were, lefties were forced to write right-handed, Jay, you're still, just by virtue of the structures that you live in, forced to be right-handed about certain things, right?

J: I don't think so. I mean, look, I have to use like-

B: Scissors?

C: You have to use right-handed scissors.

J: I can cut with my right hand because most left-handed people learn to accommodate.

C: That's exactly what I mean. There are things in this world that are handed, and you just have to learn how to use them.

J: Yeah, I mean, I could use both hands for lots of different things. Ha-ha.

C: Left even more likely to be ambidextrous.

J: I can shoot a gun both ways. I can swing rackets both ways. I can't golf both ways.

E: No swing, no backswing.

J: And I golf right-handed, by the way.

S: Oh, yeah?

J: Yep.

S: But you shoot bows left-handed?

J: I shoot bows left-handed, but I could shoot the other way. I could shoot just as good the other way.

C: So you probably can't remember, but I'm curious about y'all's experiences because Jay's the baby. You know, my best friend has a little girl who's about to turn two, and it was obvious so early that she was left, that she is going, we say going to be, but whatever, that she is left-handed. She just does things with her left hand that seem weird to us, but clearly are very natural for her. When did you know? Like, did you guys notice that Jay was left-handed when he was a little baby?

J: The first indication was when I was probably about three or four years old, I was sucking my left thumb.

E: That develops in the womb, thumb-sucking.

C: That's interesting.

J: I probably was doing that even earlier.

S: It emerges between 18 months and four years old, so that's not unusual.

C: This little girl is using her spoon with her left hand. If you hand her a crayon and she goes to take crayon to paper, she always grabs it with her left hand.

S: Will she cross the midline with her left hand?

C: I don't know. We should check.

S: That's the test.

J: Cara, for sure, now that I think about it, we always knew. My mom and I always knew.

E: I always knew there was something different.

C: And so, did you know that, okay, I think, and Steve, maybe you can fact check me on this, or somebody can Google furiously, that left handedness occurs in about 10% of the population, and that about 10% of those lefties have their language center of their brain lateralized to the right.

S: It's something like that.

C: It might even be something like 10 by 10. Yeah, it might not be a perfect number. But so I wonder, Jay, have you ever had like an fMRI?

J: I don't think about this. No. I've had MRIs, but nothing-

C: Like a brain scan that shows function. I would be so curious.

S: The estimates are between 15 and 30 percent.

C: Oh, wow, that high.

S: I'm sure dominant for language in left-handed people. And it's like 2 to 5 percent in right-handed people.

C: Oh, that's much higher than I thought. That's amazing.

S: Yeah.

C: Yeah, that's so interesting.

S: We have to know that when you do a neurological exam, you're supposed to ask and record the handedness of the person for a couple of reasons. One is when you're interpreting the exam, they should be a little bit better with their dominant hand and their non-dominant hand on some of the things we have them do. And if it's reversed, that could mean that they have a stroke, that they're impaired with what should be their dominant hand. But also, when we're localizing like a stroke, for example, you have to know if there is a reasonable probability that they're cross dominant, right, that they're right hemispheres.

C: Yeah, you need to know functionally how those things are going to affect them then. And also in like from a neuropsych perspective, the neuropsych assessments that are given, handedness matters for a lot of the motor assessments because they're normed. And so if you don't know about their handedness and you look at the norms tables with an assumption that somebody is right-handed, you may misinterpret their scoring.

S: Yeah, that's interesting. And Evan, before we started the show, you were asking about the genetics of handedness, and the short answer is... It's complicated. It is not a like one gene, one trait thing. It's not even necessarily just like it's a multi, I mean, it's definitely multi gene, but we don't think we could predict based upon the genes because it's partly developmental too, right? Meaning that it's not a hundred percent determined just by the genes. So there's no simple inheritance pattern is the bottom line. Like for Jay, everyone else in our family is right-handed. Jay's an isolated left-hander, you know?

C: And Jay, what were you saying about you and your wife and your kids?

S: Yeah, so my wife is left-handed, but my kids are both right-handed.

C: That's fascinating.

S: Yeah, children of two left-handed parents are still more likely to be right-handed, even though they're more likely to be left-handed than people born of right-handed parents, right? So there is an increased probability, but it's still the minority.

C: Oh, and even just recently, like there was a study that was literally just published in April of this year, where a rare genetic variant was identified that presents in fewer than 1% of people. But in those people, they're 2.7 times more likely to be in lefties than righties. So it's like they're still identifying the complex genetics.

S: Yeah. And identical twins, they're more likely to get a higher chance of matching their handedness, but they can have opposite handedness, which tells you it's not 100% genetic. Otherwise, it would have to be the same every time, but it's not.

C: And usually they also would look with twin studies, right? You want to look at those really interesting studies where they were, where they're monozygotic, but they were raised separately, and see if that varies based on raised separately versus raised together.

S: So that's left-handed this day for you.

C: Huh.

ES: Yeah.

C: Wasn't, uh, is it Flanders? Was he left-handed?

S: Yes.

E: Ned Flanders from the Simpsons.

S: Yeah, he had the Leftorium or something.

C: Right. Yeah, the Leftorium.

E: The Leftorium.

C: I think there's one of those in, like, at Universal Studios here. Something like a left-handed-

E: With legitimate left-hand devices for purchase?

C: Yeah.

E: Oh my gosh.

C: Don't quote me on that, but I'm pretty sure there is, or maybe it's at Disney.

E: I wouldn't be surprised.

S: Jay, the thing that's always, to me, would seem like this would be the thing that would annoy me most about living in a right-handed world, if you were left-handed, is that when you write, you have to push your letters rather than pull them, and you have to move your hand over what you've already written.

C: Yeah, so your side of your hand's always smudgy.

J: Always. Always get blue on my pinky and palm, like side of my palm. And I have sloppy handwriting. I think a lot of lefties do. It's very difficult to write neatly. That said, you know, I don't care.

S: Yeah.

E: Well, you use a keyboard more than you write, mostly.

S: Now it's not as big a deal.

E: Your left-handed dominant keyboard?

J: I love writing with pen and paper, though. I love using pencils and pens and whatever. I've always loved to do that. I love to draw, even though I don't draw well, but I do it all the time.

S: Are you one of those people, Jay, who left-handers who writes above the words rather than below?

E: Oh, interesting.

B: That's weird. I remember that.

J: What do you mean?

E: Tell us about your childhood.

S: So, like, when I write, my hand is below the sentence I'm writing, but I've seen left-handers who hold their hand above the sentence that they're—

B: They bend their wrist a little down.

S: They bend their wrist down, but they're hooking it from the top rather than just being from below.

J: Yeah, mine's parallel.

C: Oh, my gosh. Okay, so I had a question come up. I had a question come up and I just googled it and BBC Science Focus covered it. I was wondering, are there more left-handed people in cultures where they write right to left?

E: Oh, I see Arabic, Hebraic.

C: Yeah, exactly. And apparently, according to this article written BBC Science Focus by Louis Villazon, quite the reverse. Various surveys have found that the highest incidence of left handedness is in Western countries, with about 13% of the populations in the USA, Canada and the Netherlands. The UK is just behind it. Most of the countries that use right to left are predominantly Asian and Arabic, and they have left-handed witness rates below 6%. So it says in Muslim countries, the advantage of smudge-free handwriting is outweighed by the fact that the left hand is considered unclean.

E: Right. It's cultural.

C: Yeah. Fascinating. I love learning new things.

B: No, you don't.

E: We didn't even know until 20 minutes ago that it was a left-handed day, frankly. And here we are.

C: Here we are.

E: Learning.

S: I wonder if that also has to do with that they killed the left-handed people more in the past and then selected against it.

E: Those little genetics.

C: And then also just trained out of it culturally.

S: But that wouldn't really affect the genetics of it, if it's still not accepted. But I'm saying throughout history, because this has been true in many cultures, even in Western cultures, that being left-handed could be a sign of the devil or the sign of whatever. And they were more likely to be persecuted, more likely to be punished and executed. And I wonder if there's just different cultural differences in how aggressively they slaughtered left-handed people actually affects the probability of being, yeah, the incidence of right-handed versus left-handed.

C: Yeah, it makes you wonder if that history wasn't there, would it be more like half-half or, you know, what would be the variation?

S: All right.

Special Segment (12:07)

New Scam

S: Jay, you're going to get us started with a discussion of a new scam.

J: All right, so I picked a particular topic of so many. I was just talking to Bob before the show. I was reading about a scam on elderly people to rob them of their retirement, which I'll talk about in another show. But I'm going to talk about election-based scams and how they manifest and how they could affect just average people. One thing that they do, you're probably aware that they send phishing emails. They'll send emails, they create websites that appear like official websites. They might ask for personal information like your social security number, your voter registration details. They might say to you that they want to confirm that you're registered or are you eligible to vote. They're just trying to get personal information from you. And then with all of these I'm going to read to you. You've got to be careful and make sure that you're on the actual official websites. This is hard because they can make the website look exactly like the original.

S: Never click a link. Go there directly.

J: Yeah, so you need to be very, very fastidious about this. They have fake donation pages. This is very common. You get a lot of texts asking for money. Scammers will set up these fake donation websites for political campaigns, and the pages look very convincing. They use official-looking logos. They might be using the exact real logos. They can just download them off the other websites. And they're going to try to get them to you through text and email, social media. The money that they collect does not go to anything but the scammer, and it's not going to the political cause, and you cannot not get taxed on that, which you normally can for other types of donations. They have voter suppression tactics. Some scams are aimed to simply suppress voter turnout by spreading misinformation, things about voting procedures, incorrect polling locations, fake deadlines, misleading information about your voter ID requirements. These are all out there just to confuse people. Again, go to your state or town website, find the information yourself, don't let people send you the information. Go get it yourself. Phone scams pretending to be pollsters, this is very common. Scammers will call people pretending to be conducting political polls, and during that call, they might ask you for sensitive information, saying it's necessary for the poll, make sure it's unique, they don't double, ask people questions, all that stuff, it's all BS. They're just collecting your personal data and they want to commit identity fraud on you. The text message scams, I get a ton of these. Scammers will send text messages that they're pretending to be from, again, you know what I'm going to say, political campaigns, websites. It could be from the person themselves. It could be Trump or Harris that is going to be texting you directly. With your name, hey Steve, blah blah blah, send me money, right? You've got to be really careful. If you want to donate money to a political campaign, just make sure you go to the official websites, do some searching yourself, chat GPT, whatever, but do the research yourself. Don't respond to things that people send you. And then fake voting assistance services. Scammers may offer services that are there to assist you with voting, such as helping you filling out absentee ballots, offering to deliver the ballots on your behalf, blah, blah, blah. These services are typically fraudulent, and they may steal your vote and personal information. Imagine that. You find out that they cast a ballot for the exact opposite person you want to be in office. So to protect yourself from these scams, election scams, other scams, it's important to verify any election-related communication through the actual official channels. Going to the state websites is a good idea, or your town websites. Verify the links. Just be fastidious. The other thing is, never provide personal information in response to unsolicited requests. Ever. Ever. If your Social Security number is in play, if they want bank information, if they want anything that feels like they shouldn't need it in order to do what they're doing, make a huge red flag go up and do not do it. Always call back. Tell them, hey, I'm going to call the official phone number on the website. If they give you grief about that, it's a scam. You know what I mean? You just got to be really careful. And then this is really important. And I've said this before. Tell everybody in your life, especially old people, what I just said. All of this stuff. Because statistically, the older people are, the more likely they are to fall for these scams. And it's just really easy for you to call up your mom or your dad or whoever and just be like, hey, guess what? You know, you got to watch out. People are, we're in election season here. People are going to be soliciting you for personal information. They could do lots of different things to you. Just don't respond to anything and say things like, hey, if you want to donate any money, I'll do it for you. Let me know and I'll take care of it for you.

S: All right, thank you, Jay.

News Item #1 - Childhood Vaccines (17:16)

S: All right, Cara, tell us about childhood vaccines. Are these a good thing?

C: I don't know. What do you think, Steve?

S: I might have an opinion.

C: Maybe a little one. So the CDC just released in their morbidity and mortality weekly report a report on August 8th. Titled Health and Economic Benefits of Routine Childhood Immunizations in the Era of the Vaccines for Children Program, United States, 1994 to 2023. So if you didn't know, since 1994, here in the United States, there's been a program called Vaccines for Children, VFC, which has covered the cost of vaccines for children if their families would not otherwise have been able to afford the vaccines. And so this study looked at the health benefits and the economic impact of routine immunization among both VFC eligible and non eligible children born between 1994 and 2023. They looked at nine different childhood vaccines. Am I going to know what these are based on their initialisms. Let's see.

B: Thank you so much.

C: You're welcome, Bob. I think this is diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. So DTP or DTaP, HIB. Hemophilus influenza type B. I think that's what that is. OPV, IPV. That is oral and inactivated polio virus vaccine. Also MMR, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, VAR. Oh, that's varicella. Oh, I'm so jealous. I wish we had varicella vaccines. We all had to get chicken pox. And then Rota. So that's the Rota virus, I'm assuming. So what do you think they found? It helped, right? No, but let's look at the magnitude of these findings. And then I want to talk a little bit about something that is very worrisome based on a recent Gallup poll. So among those children born 94 to 2023, based on the analyses in this report, routine childhood vaccines would have prevented approximately or had prevented approximately 508 million cases of illness, 32 million hospitalizations, and 1.129 million deaths, 1,129,000 deaths.

J: That's incredible.

C: And now let's talk about-

B: Over how much time?

C: That's a long span. That's almost 20 years.

B: Okay, wow.

C: No, almost 30 years, 94 to 2023. You know, it always feels a little icky when we talk about cost savings when something that is, as extreme as illness and death. But it does cost money to treat disease, and it costs money to try to save a child who has a vaccine-preventable illness. So according to this report, there are two different ways that they looked at these cost savings. The first one was direct health care costs, and the direct health care costs they saw a savings of $540 billion. So $540 billion in just the direct health care that would have been required if these children had not been vaccinated. But then they looked at something even larger, and they said, OK, well, even more than that, what are these other costs, these kind of externalized costs, these societal costs? And they estimate that at $2.7 trillion. And that includes things like, what if your parents have to stay home from work to care for the child while they're sick and they lose wages from that? What if a child becomes permanently disabled from an infection, which can definitely happen? And then there are costs throughout the lifespan of supporting that child. So those additional costs bump that estimate up to 2.7 trillion. That seems to be on par with savings from like curing hepatitis C or savings from the legislation like the Clean Air Act. The ROI on childhood vaccines is literally bananas.

S: Yeah, it is.

C: The amount of lives saved.

S: It is the most cost effective public health measure.

E: Of prevention, always.

C: 100%.

E: When is prevention not one of the best health savings.

C: Right. And vaccines especially, I mean, because it's like really well-established prevention. So here's the thing. That may be the reality of the situation, but a recent Gallup poll, and when I say recent, this was published August 7th, the polling was done from like July 1st to the 21st, 2024. So this is pretty recent. A Gallup poll showed that there have been a lot of changes in how U.S. adults view childhood vaccination. And this is pretty scary. So when asked if it is important for parents to have their children vaccinated, we saw a huge change. And that change was heavily lateralized according to political affiliation. And where do you think the biggest changes have taken place? This data was from 2002 to 2024. We can look at trends across that line. What political party do you think saw the biggest change in their views?

B: It's got to be the Republicans, right?

E: Republican or Democrat? Republican.

C: So historically, we often think of vaccine hesitancy, vaccine denialism, as sort of being like an anti-science or a pseudoscience problem on the left. But what's interesting is that it's actually long been pretty consistent across political parties. What's really interesting is that in the past only like four years, there's been a massive shift in Republican views. So when asked, for example, how important is it that parents get their children vaccinated? Extremely important, very important, somewhat important, not very important, or not at all important. Those who answered extremely important in 2002, it was 66% of Democrats and 62% of Republicans. In 2020, it was 67% of Democrats and 52% of Republicans. In 2024, 63% of Democrats, 26% of Republicans.

E: Yeah, it's tanking.

C: They asked, how important is it that parents get their children vaccinated?

B: Wow.

C: So again, back in 2001, on average, 94% of respondents said that it was extremely important. And only 69% of respondents are saying extremely important right now. Massive decline in these viewpoints. We've also seen, some change, some other trends and changes across the board, but I think this one is the most telling, and it's the most worrisome, because nothing changed in early, actually, this was sorry, when I gave you those numbers before the 2020 to 2024, it was really late 2019 to 2024. So it was, of course, pre-COVID versus after. So nothing changed, except the rhetoric. Right? The outcomes of childhood vaccinations were just as strong. The health consequences, those lives saved, the amount of money saved within the economy, just as robust. The only thing that changed was the rhetoric. And then here's another big one that I think I'd be remiss if I didn't mention. Here's another question that was asked. Do you think vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they are designed to prevent? So once again, do you think vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they are designed to prevent? Overall, in 2001, only 6% of people said yes. They are more dangerous than the diseases themselves. In 2024, 20% of people said yes.

E: Crazy.

C: And when you look at the difference between Democrats and democratically leaning individuals and Republicans, republically leaning individuals. 2001. Six percent of Republicans said yes, the vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they're designed to prevent. Five percent of Democrats said yes. 2019. Twelve percent of Republicans said yes. Ten percent of Democrats said yes. 2024. 31% of Republicans said yes. 5% of Democrats said yes. 31% of Democrats who, I'm sorry, of Republican respondents to this Gallup poll in July of 2024 said that vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they are designed to prevent.

J: Amazing.

E: That's some powerful influence.

C: You know, like not only is this a beautiful example of a theme that we often talk about on this show, which is that the data, the actual data, which is easily accessible, is completely out of step with the rhetoric and the beliefs on these highly kind of charged political topics. But it's also a beautiful example of how, how much influence certain individuals can have on the viewpoints of many people in this country and how those changing viewpoints will directly affect public policy.

E: Oh my gosh. We've known this especially since the vaccines cause autism from the late 90s and early 2000s. We've seen this.

C: But – and you say that, Evan, that we have seen this. But if you actually look at the data, the vaccines cause autism scare in the 90s and 2000s. Yes, it did affect trust. You do see a change. But I don't think it was this extreme.

E: Because the internet wasn't as widely accessible back then as it is today. So that that's definitely part of it.

C: It also shows this tendency that we have, this sort of cognitive bias that we have to take fear mongering, information that was fear mongering, and then apply it to other aspects of our thinking. Because most of the rhetoric was COVID vaccine rhetoric. Yet we are seeing a massive impact on questions about whether parents should vaccinate their children against childhood diseases.

E: Yeah, well, it's a deterioration of trust and authority.

C: Yeah, it's really scary. You know, I think that this is a big deal because what we're seeing now, this study about the Vaccines for Children program is showing us the real impact of vaccinations. This Gallup poll is showing us what people think right now. So I'm kind of scared to see the outcome studies in five to 10 years of children who were refused their vaccines by their parents and how they fared.

E: Well, we start to see the reemergence of some things that we haven't seen in a long time.

C: We've already have been. I mean, we've been seeing measles outbreaks. That would have been unheard of.

E: Yeah, we have seen those before. You know, we've talked about the California, right, the whole Disneyland thing. We talked about Minnesota kind of being a hotbed for that occurring every now and again.

C: And I can tell you like, and this is just, a personal experience thing. So all of us on this podcast are old enough that we got chicken pox, right?

E: Yeah, I did. Yep. Age 11.

C: Did any of you have any of you had shingles yet?

B: I did.

E: No, I'm supposed I didn't get it.

J: I got the vaccine.

E: Yeah, I'm supposed to get mine soon. Yeah.

C: I'm not eligible yet for my vaccine, so I'm in the scary spot. My kid's sister had shingles recently. Multiple patients that I work with in the cancer center have had shingles. It is violently painful.

E: Oh yeah, gosh.

C: And especially if you're already struggling with diseases that affect your immune system, if you're already struggling with these other issues. If you are a cancer patient and you have shingles, it is not a picnic. And I see it, I see it weekly, and it's just devastating. And yes, we're all from a cohort where we didn't have access to the vaccine, or the vaccine, or for some of them, they're younger, right? But we all have the virus in us. And so the vaccine is there to help with that, with that flare up. But kids today will never know that pain. And to deny them that vaccine. And of course, I have a vaccine preventable illness that caused cancer. I had to have a drastic surgery, I had to have a hysterectomy to remove my cervix because my cancer was caused by a vaccine preventable virus. That vaccine didn't exist when I was exposed, but you know, it happens. And like, I wish I was lucky enough to be vaccinated. I'm vaccinated against that disease now. But I wish I was lucky enough to be vaccinated. And it just it really like, I think it's more infuriating. And it feels that much more of a dig when you see people saying I'm not going to vaccinate my kids or vaccines aren't important or the vaccine is worse than the disease when it's like you don't have the disease dude. Let me tell you, I'd much rather not have this disease. And I have both with this. I am vaccinated and I have the disease, right? I can tell you the disease was worse. It's infuriating.

S: I think this is part of a bigger trend of distrust in authority. And at some critical point of distrust, people are like, well, screw it. I'm just going to think whatever I want to think. You know what I mean? I'm just going to go along with my tribe or just let confirmation bias completely overwhelm what I believe because I don't have to accommodate or listen to expert opinion because the experts are not trustworthy. You know, where institutions are not trustworthy. And that, I think, is the biggest negative effect cumulatively of a lot of the divisiveness that we have, where institutions become collateral damage, I think, in a lot of political fights that we have. And I think also social media has done this as well.

C: Oh, yeah, I agree.

S: Because everyone thinks they're an expert.

C: And it's a perfect storm because it's occurring against a background of The thing is working so we don't notice it. You know, like, well, why do I need to vaccinate my kids? Nobody's sick out there. Well, yeah, because of the vaccines.

S: Right.

C: And that that becomes that's like that negative consequence that comes like the hidden value in these things. You don't see polio in the United States anymore.

S: You don't see the non events. It's like Y2K. Oh, we made a big deal over nothing. No, it was nothing because we made a big deal.

C: Exactly. Yeah.

E: Ask these same people to take down all their protection services for their computers and see how long they last without getting infected. I bet you they wouldn't be so quick to poo-poo, you know, virus protection and other things.

C: And that's your laptop. That's not your body, your health, your livelihood. I mean, these diseases kill children. And the children they don't kill, they often maim. They often cause, like, permanent disability.

S: Lifetime problems, yeah.

C: Yeah.

E: Sure.

C: Yeah. This is not, you know... I'm emotionally invested in this topic, as we all should be, damn it.

E: Are there any suggestions for what can be done, or do we have to let it play out and hope the culture changes?

C: Well, I mean, that's the thing, like think the things that need to be done are being done. Like, again, we have a program in the US where children who would not otherwise be able to afford to be vaccinated can get vaccinated for free.

E: As long as their parents...

C: Exactly. The CDC understands the need for this. Many schools have vaccine requirements for your kids to be able to mingle with other kids in those schools. So there are systems in place to protect us from a public health perspective. But at a certain point, if you want to get out of this requirement, you're going to figure out a way to do it. You're going to homeschool your kids. You're going to, whatever the case may be, can't force it. So what do we do? We improve education and we hope that, we hope that the tides start to change.

S: And we have to mandate vaccines is the other thing. It's perfectly reasonable to require certain vaccines to attend public school. I think companies have the right to require vaccinations if it could impact the safety of their fellow workers or their customers.

C: I can't go to work without my flu shot and my COVID shot.

S: It's now a plank of one of our major parties to remove that requirement, right? That remove all federal funding for any public school that mandates any vaccine. There's an actual reasonable chance that that could become law in this country.

C: And it's in perfect lockstep with this Gallup pole. That's the rhetoric. Well, disaster.

S: That would be disastrous. Thanks, Cara.

C: Yep.

News Item #2 - Alien Solar Panels (35:12)

S: All right, Bob, tell us about alien solar panels.

C: Yeah, that sounds like a much happier note, Bob.

E: Yeah.

B: Yeah.

C: Get me out of the dumps.

E: I didn't know aliens had solar panels.

B: Well, the question is if they did, could we detect them? That's the question. So in a recent interesting study, the researchers created a model of an Earth-like planet, and then they covered it with modern solar panels that would meet all of our current and near future energy needs. They then imagined that it was a distant alien exoplanet to see how detectable it was with near future telescopes and how much planet-wide panel coverage aliens might need. And that seems much more of a complicated sentence than I intended, but what did they find and wouldn't you like to know? The study was published in the Astrophysical Journal called, the study is called, Detectability of Solar Panels as a Technosignature. A lot of research for extraterrestrial life focuses on biosignatures, right? We've said that on the show many times, such as the molecules of life in exo atmospheres or specific frequencies of light reflected or emitted from surfaces that point to some sort of life forms. My favorite though is not biosignatures. As my grandfather used to say, bio signatures, peh, I love technosignatures, the manifestations of alien technology that we can observe. That's what a technosignature is. I mean, who doesn't like the idea of actual alien technology? To me, that's just like, oh boy, more of that. So this study focuses on potential technosignatures that are used to power these alien civilizations if they exist. In this case, they were focusing on silicon-based solar panels. Now they focus on silicon instead of other photovoltaics using things like germanium or gallium, which are much lower in abundance universe wide. So that's why it seems kind of all right, if you're going to go with a material that these solar panels are made of silicon sounds like a good idea. Alright, so the first reason they chose silicon is that it's like I said, silicon was chosen partly because it has a high cosmic abundance. It's all over the place. So there's a higher probability that aliens would probably be using that. Reasonable I guess. Also, number two, the electronic structure of silicon, its so-called bandgap. You may have heard of that. That works especially well with the radiation emitted by sun-like stars. And finally, number three, silicon also happens to be very cost-effective. When you refine it, process it, manufacture it into solar cells, it's relatively easy. So those three reasons, it seems reasonable. Okay, maybe aliens would use silicon if they're going to use that at all. So then the researchers also relied on this idea of what's called artificial spectral edges. I've never heard of that, but it makes sense once you see where they're coming from. This means that there's a dramatic and detectable change in the reflectance distinguishing silicon from non-silicon, right? And this is specifically in UV wavelengths. So imagine you're scanning the surface of an alien planet and a big chunk of the planet has got all this dirt. And next to the dirt is this sandy desert area. And then next to that are these gargantuan solar panels. So as it's being scanned or observed from a distant telescope, there would be a rapid increase in reflected UV light that would be easier to detect, right? So as you're transitioning from one area like a desert to this area with lots of solar panels, you're going to see a spike in the UV wavelengths. Like, oh, that might be a solar panel. So there's that. And it's similar to satellites detecting vegetation on earth. In this situation, they have – it's called vegetation red edge. So that's because chlorophyll absorbs a lot of infrared. So the infrared drops sharply when you look at vegetation. So you're scanning – satellites are scanning the earth. You're going to see a big drop in vegetation. That's one big indication that, oh, yeah, there's vegetation there. And that's called vegetation red edge. So it's kind of – it's very similar to this artificial spectral edge. The researchers then made a model of an earth-like exoplanet. And to this exoplanet, they added these different land categories. They added ocean, snow and ice. They added grass, forest, and bare soil. And then they added a sixth category, solar panels. So those are the five land categories or six land categories. Of course, there's a huge bias there, right? Those are land categories that we have on earth. But who knows what the exoplanets would have. Although I assume that it's not unreasonable to pick those, especially for a planet that has some life. Then they moved their model planet 30 light years away. And they determined what would they see if they looked at it with a really cool telescope. So the really cool telescope that they chose was NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory Telescope. So this is planned to be launched in 2040. It's going to hopefully have a 6.8-meter mirror. And it will look for life on earth-like exoplanets. So that's a big one that they're planning. I hope the plans come to fruition even though it might be dead. But it would be still nice. So that was the scenario. They had this model planet, this exoplanet that's similar to earth with all these land areas. And one of the land areas consists of lots of solar panels. And they wanted to see, can we see this thing from 30 light years away? So they did all of their work. And they concluded that detecting such panels, given their hypothetical scenario that they created, would still be very hard, even 30 light years away. Which to me sounds damn close, but it is extremely far away. But still, it's relatively close. But it was still very, very hard to see these solar panels even when there was a huge amount of them. They concluded that solar panels would often be indistinguishable from non-panel features on the exoplanet, whether it was the other land categories. It would still be hard to distinguish them. They said that detecting the large panels would likely require several hundred hours of observation. So that's a lot of observation, several hundred hours to be focused on a planet looking for solar panels. That's a lot of time. And then also if the planet happened to have very large solar panels covering a quarter of the planet, say 25%, of course that would make it easier to detect them. But the scientists said that even that would be difficult to do, even if there was a lot of them. So bottom line, it would still be extremely hard to see, to detect these solar panels, even though they might be bright in the UV and there might be a lot of them. It's still hard. Even with a really cool advanced telescope, it would be hard. But they also found something else that was interesting. Lead author of the paper, Ravi Kaparapu of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center said, we found that –

C: Spice.

B: Huh?

E: Spice.

C: Spice.

E: Yeah, I thought you were going spice.

B: Do you like spice? I love spice. No, outer spice. All right. We found that even if our current population of about 8 billion stabilizes at 30 billion – and I think that number, 30 billion, is the number that has – they did some study and said, yeah. If we're going to max out people on earth, it's going to be about 30 billion. Let me start this quote again because I'm throwing in my own words. All right. Ravi said, we found that even if our current population of about 8 billion stabilizes at 30 billion with a high standard of living and we only use solar energy for power, we still use way less energy than that provided by all the sunlight illuminating our planet. Okay?

E: Right.

B: That means that many advanced civilizations with tens of billions, literally tens of billions of inhabitants might not need anything ridiculous like Dyson swarms around their parent star collecting a significant fraction of light from their sun. The researchers showed that with 8.9% of the land surface of a planet covered in solar panels, that would be enough for 30 billion people to live to a very high standard of living and we still wouldn't be able to detect those panels. So you could literally have 30 billion aliens 30 light years away with 9% of their land mass covered with solar – highly reflective solar panels and we still wouldn't be able to detect them. Now remember though, those panels could be on the water. They could be in orbit. It doesn't have to be on the land. I mean 8.9% is still a lot. I mean that's essentially what like covering China and India with solar panels. I mean that's a lot of solar panels. But what if that could supply your entire planet with power for centuries? That would be interesting. Kopparapu also ties this study to the Fermi paradox and the Fermi paradox, if you don't remember, asks the question, where are the aliens? Why haven't they spread all over the galaxy by now or the universe by now? They've had literally hundreds of millions or billions of years to do so. Where are they? So Kopparapu said regarding that, he said, the implication is that civilizations may not feel compelled to expand all over the galaxy because they may achieve sustainable population and energy usage levels even if they choose a very high standard of living. They may expand within their stellar system or even within nearby star systems, but a galaxy-spanning civilization may not exist. So that was the study. It was a fun read and it was interesting as far as it goes. But I mean it's obviously clear. The human bias, of course, is written all over this, right? I mean it's hard to extrapolate. As we know, with one data point of life, it's hard to extrapolate on other alien civilizations what they would be like, what they would need. How much power, how much energy would they need to live comfortable lives? Would they spread? We have no idea. We have no idea. So I think this study is – maybe it's more predictive about not what aliens would do but what humanity would do. Maybe for the next two or three centuries, with solar panels and fusion energy, we may not be very detectable at large distances either. We could have plenty of energy available to us without any gaudy Dyson swarm around our star. So maybe that's one of the takeaways is that using maybe some solar panels in orbit, some on the earth and also fusion, of course, whatever other energies we may use. I mean we could have plenty of energy even if we go up to 20 billion or even 30 billion. So that's an interesting angle. But of course, the more alien your aliens are, then I think all bets are kind of off to a certain degree. And the more godlike their technology is, all bets are off because you have no idea what they're doing. I mean imagine a Kardashev level 3 civilization. We would really have no idea what they would do, how much power, how much energy would they need. What would they do with it? Would we be able to even detect it? It's kind of like ants trying to figure out what are those two people doing over there? It's like they have just like no idea. It's kind of silly to try to think we could even come close to understanding or figuring out what that would be like. But still an interesting study.

E: So it's indiscernible in other words.

B: Yes.

E: It's mistaken. You could never suss out the fact that there's all these –

S: Well, they would have to be close and massive is what I'm hearing.

B: Yeah. Yeah. So maybe this does explain – maybe that's why they have done some decent searches for technosignatures like Dyson Swarms. We've had some – lots of news items about them but nothing definitive or even close to being definitive at all.

E: Yeah, but don't they know that we want to know them and they should broadcast to us so we can find them?

B: Yeah. Aliens tend to be that way.

S: What if we're basically alone in our galaxy? That is not unrealistic.

B: No, absolutely. But we have no idea. We have no idea. But yeah, it's absolutely, it could be...

E: It's our galaxy.

B: Imagine the next life being, you know...

S: A galaxy over it, yeah.

B: Or a hundred thousand, far outside our, you know...

S: Our local group.

B: Our local group. I mean, imagine that. But I suspect, Steven, I'm sure you do too as well, that there's life all over the place, but more microbial life. This is really about advanced sapient life that can manipulate technology in ways we would be impressed with.

J: Bob, what do you think would happen if they found a real Dyson sphere? What do you think would happen socially around the world?

B: I think a lot of people wouldn't believe it. I don't think – ultimately, I don't think it would have much of an impact because there would always be some doubt that it was natural.

S: And even if we eventually – like the scientific consensus landed on, okay, this is definitely a technosignature, that would take a lot of time. This wouldn't be like an instant affirmative conclusion. It would be like there's a potential one. And we would say, yeah, like the last 1,000 potential ones they all crapped out. And say, wait a minute, this one would survive more and more tests. It would probably be a process that plays itself out over years. Yeah, we would creep up on the consensus. It wouldn't be a sudden shock, you know what I mean?

C: But I don't think it would happen. You're right scientifically, but I think that socially, religions would be formed around this. Weird cults would start.

S: Eventually, maybe.

C: Yeah, there'd be all sorts of like, pseudo science and nonsense.

B: Not much would surprise me. But I think once as we become increasingly convinced that it was that it was a real techno signature, I could imagine a lot of money spent on projects to really-

E: Yeah, then you could-

B: -observe it.

e: You could make a specific tool, right? That that is going to hone in on that thing and try to confirm it. Yeah, that that would happen.

B: But I think it would take a while to get there.

News Item #3 - Dragon Capsule (51:06)

S: All right, Jay, tell us about these astronauts that are stranded on the International Space Station.

J: Yeah, we have two NASA astronauts, Sunita Williams and Barry Butch Wilmore. How come they didn't give her a space name, you know?

S: I don't know.

E: Like a nickname?

J: Yeah. You know, they all have to have a cool-

B: I'm sure she's got a nickname.

E: What was her name again?

J: Sunita Williams.

E: Sunita Williams. Super Sunita Williams.

J: I like it. So they're currently stuck on the International Space Station, and this is due to ongoing technical issues with the Boeing Starliner spacecraft. Not a great position to be in. So Williams and Wilmar, they were delivered to the space station on June 2024 aboard Boeing Starliner. Now, this was a spacecraft that was developed as part of NASA's Commercial Crew Program, which we've talked about. The mission was supposed to be pretty straightforward, with the astronauts staying on the ISS scheduled for about a week. And even before the launch, the Starliner encountered some technical difficulties and the new issues with the thrusters emerged after docking at the ISS. What happened was they just discovered that there was problems with the thrusters. They docked and then NASA is currently testing the Starliner spacecraft while it's stocked at the ISS. I didn't know that this was possible. The testing is focused on the spacecraft's thruster system. Like I said, NASA engineers, they're carefully running these tests. They're trying to evaluate the performance and the reliability of the thrusters before they make any decisions regarding how the astronauts are going to return to Earth, which is a vital piece of information that they're trying to get to. Now these tests include monitoring the spacecraft systems and simulating various scenarios that would ensure that the Starliner can safely undock and re-enter Earth's atmosphere. So the results of the test will determine whether the Starliner will be used or if they have to result, turn to an alternate spacecraft. And some of the options could be a SpaceX Crew Dragon or a Russian Soyuz. So right now they don't know exactly what the problem is still as far as what I could find out as of today. They're feeling like they need to continue testing. And I was personally very surprised that they could test this as thoroughly as they are testing it while it's docked at the space station. That's awesome. And the genius of the engineers and in the foresight of the engineers is what is Hopefully going to pay off here. So the astronauts themselves, they're both in good spirits. They have a lot of confidence that the testing and the safety of the Starliner is going to come out on top. Now in case of an emergency, NASA and Boeing publicly stated that the spacecraft is equipped to undock from the ISS and return the crew to Earth safely. That's what they're saying today. But, under normal circumstances, the spacecraft will not be cleared for return until the thruster issue is fully resolved. So in the meantime, the other spacecraft docked at the ISS. Now, this article I read said something that a second article didn't, and I don't know exactly what's going on. Now, is there currently a SpaceX, Crew Dragon, and Russian Soyuz at the space station right now? There was inconsistencies with these articles. So anyway, they're trying to assess all these things at the same time. The engineers are taking a very careful approach. They want to have a possible return window of mid-August, which is, you know, now, coming up very soon. But this could extend, and they could stay there longer depending on how the tests go. Now, the technical problems are not resolved in time, and there's no alternative spacecraft available. This is the worst case scenario. There is a possibility that the astronauts could remain on the ISS longer as planned, and some reports have mentioned that the stay could extend into 2025. It's a pretty extreme position, but it is a speculative outcome. They're talking about it, of course, just in case it happens. Bottom line is we have to wait a little bit longer. Now, the Starliner is approved to remain docked at the ISS for up to 45 days. This is largely because of the batteries aboard. They could extend that to 90 days using backup systems. The health of those lithium-ion batteries is always a question here. These batteries have previously caused problems and concerns, and that adds another layer of complexity here. So an interesting thing I found, too, this was pretty cool. So a Russian satellite broke apart. It created debris that briefly threatened the space station. And during that incident, the astronauts, both of them, had to go into their spacecraft for protection, which I found to be very curious and interesting. I guess there's only a certain number of places that they consider to be safe and the spacecraft are very safe. So we will see what happens here. I mean, I'm not worried at all. I feel like NASA's got this and the future here is going to probably reveal itself within the next couple of weeks.

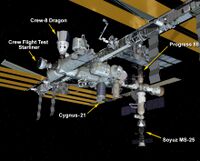

S: Jay, what I'm finding is that the ISS currently has six spaceships docked to it. The Boeing Starliner spacecraft, SpaceX Dragon Endeavour spacecraft, Northrop Grumman resupply ship, Soyuz MS-25 cruise ship, and Progress 87 and 88 resupply ships. All docked to the ISS right now.

J: Wow.

E: What's in docking bay 94?

S: So they have options. They have the they have a Dragon cruise capsule and a Soyuz and then the rest of resupply ships, I guess, are not crew approved.

News Item #4 - Framing and Global Warming (56:44)

S: So guys, what do you think of when I tell you the word framing?

J: Framing?

S: In the context of science communication. What do you think of the term framing?

C: Oh, yeah, like it's a strategy for ensuring that the The listener is going to approach it in a way that, that you want them to. It's a persuasion strategy, I guess you could say.

S: So, do you guys remember? This might have been a little bit before you were actively paying attention to the skeptical movement, Cara. But maybe 15, 20 years ago, there was a very brief debate within skeptical circles about whether or not framing was a scientific or more of a deceptive practice. Like there was a couple of people talking about we have to frame our messages appropriately. And other people, other skeptics were like, that's deception. That's politics. That's propaganda.

C: What? All science communication is persuasion.

S: Well, I mean, it's all- And the other thing is, yes, I agree with you. But also, you are always framing your message.

C: True.

S: Whether you think you are or not. So it's like saying, oh, we're doing science, not philosophy. It's like, no, you're doing philosophy. You just don't know it.

C: Right, when somebody's like, no, but this is pure information.

S: Or whatever. You're just not aware of the, or thoughtful, therefore, about the philosophy that you're using, or in this case, the framing that you're using.

C: Or the bias you're bringing to the table.

S: Yes. Exactly. So you're using an unconscious or assumed framing without even knowing you're doing it. That doesn't make it in any way better. We're pure or whatever. So it was both naive and I think I misplaced, but it was very short lived. I think it was like very quickly that the internal conversation was like, no, this is like a standard part of science communication. So there's a recent study, what's prompting me talking about this is a recent study looking at the framing of global warming, talking to the public about global warming. And they are focusing on, they wanted to see what people's reactions were to the just of term climate change versus global warming versus climate crisis versus climate emergency versus climate justice.

C: Interesting.

S: And they essentially asked two questions, or two types of questions. One was just, are you familiar with this term? Have you ever heard this term before? Do you know what it means? And the results are pretty predictable. So climate change and global warming were both very high, about 88%, roughly the same. Climate crisis, climate emergency were less so. Crisis was 76%, climate emergency 58%, and climate justice was the least at 33%. So people had not heard of that term and weren't really sure what it meant, but very familiar with climate change and global warming. Then they asked people to say whether or not this is something that you are concerned about. Like, are you concerned about climate change? Are you concerned about global warming? And the numbers were very similar.

C: Interesting.

S: Yeah, to the the familiarity one. So they concluded that there is a big effect to, when you're talking about framing the discussion, like do you frame a discussion of this issue around the concept of global warming versus climate change, whatever. People's familiarity with the terms that you're using have a dramatic effect on their receptiveness and their attitudes towards that topic. They also, of course, broke it down by political persuasion with the absolutely predictable results, right? Of Democrats being more concerned, Independents less so, Republicans less so.

C: But did they say who responds better to what framing?

S: It was just by, I think, familiarity was the determinative factor. And otherwise, the average numbers were similar to the familiarity numbers, but then they would break out based upon political ideology.

C: That's interesting because I guess my understanding was that there was a big cultural shift from global warming to climate change to make it more palatable.

S: They're both, yeah, but they're both the same in this study.

C: That's interesting. So that almost shows that over either it shows that that actually that that strategy didn't work or that it did work at the time, but it's become such a common place. Yeah, it's been normalized.

S: And honestly, that, to me, makes sense because I find that climate change and global warming are used pretty interchangeably.

C: They are. But at the time, it was really intentional. Like, if we say climate change, people will not be reactive.

S: Well, I think the idea also is that climate change is more accurate because global warming makes it sound like it's warming everywhere always, as opposed to the climate's changing. It's warming on average, but some places are getting warmer, other places not so much. And it's inconsistent year to year, whatever. So climate change is just more accurate. So is it just to avoid the straw man of, well, it's not getting warmer here now, so how can you call it global warming? Like so much for global warming. I don't think that that actually worked because the people who are making that argument were being disingenuous anyway.

C: Yeah, that's what's interesting about it is that, my take would be that calling it climate change, while it might be, quote, accurate, it's actually more innocuous as well. And so, it's much easier to be like, well, who cares if the climate changes? Is it changing for the worst? Is it dangerous that it's changing? Whereas things like climate emergency, they communicate a value judgment.

B: Crisis. I like climate crisis.

S: I think you can make a reasonable argument for not using climate emergency or climate crisis because of all the reasons that the authors here state. But in addition, because it has that value judgment. You say climate crisis, it's much easier to straw man that as a climate alarmist position. Is it really a crisis? And so you're asking people to accept not only that there's global warming, but that it's a crisis at the same time. Rather than easing them in, maybe saying there is, climate change that involves on average warming, and it could be a problem, going forward.

C: I'm actually asking, I'm texting a friend right now, she works for a firm. And she's the comms person at the firm. And their job is to partner with agencies, often government agencies. Her specialty is ocean science. But they actually draft policy, and they do work to try to make sure that budgets are protected and that initiatives are going forward. And so they have to be bipartisan. And so I'm actually asking her, do you avoid that kind of language? Like, what is your strategy? Because I'm curious how it actually works in Washington.

S: Now, here's another thought that I had, is when you use a term like climate crisis or climate emergency, those are emotional words, right? Those are more value-laden words.

C: They might be motivating.

S: So people might think that those terms are biased, and therefore they would assume that the messenger is biased. Right? The other thing is that when people hear emotional language, I think there is a defensive sort of knee jerk reaction because you feel like I'm being manipulated. And that's actually a perfectly reasonable assumption most of the time. So this is and we get we have discussed this sort of in general previously in terms of our messaging. It's like we want to accurately reflect how serious the topics are that we're talking about. Like, if we're talking about vaccine denial or anti-vaccine rhetoric, right, Cara, like you were saying, we want to say this is very serious. This could result in kids dying of otherwise preventable diseases. But if we push that framing too far-

C: Right.

S: You get a backlash. Well, now you're just emotionally trying to manipulate me rather than giving me objective science. So how do you keep the aura of objective science but still convey the seriousness of the topic that you're talking about, right?

C: I mean, there's a huge problem during COVID, a huge problem.

S: Absolutely. And we also run into the same problem when we're talking about con artists and pseudoscience. We say like homeopathy, which we're going to talk about in a moment, is rank pseudoscience. There's really no other way to accurately portray. It is complete and utter nonsense. But when you talk that way, even though it's true, you don't sound like a scientist. But if you talk like people think a scientist is supposed to sound like, you lend false credibility by damning with faint criticism in a way, right? You're not criticizing homeopathy enough with your language, and so people think that it's like something that reasonable scientists could disagree about. It's like, well, the evidence doesn't support homeopathy, but rather than saying, this is really complete nonsense. You know what I mean? So it's...

C: And there's the layer too, Steve, because we're talking about science communication and we're often talking about scientists communicating their research or people whose sole job it is to communicate science. But there's a whole other wrinkle in this, and I remember having debates about this for years, which is that science journalism is very different from science communication.

S: Yes.

C: Science communication often by definition is agenda driven.

S: It's persuasive.

C: Yes, it's persuasive. Whereas science journalism, I mean, talk about exactly what you opened this conversation with. Their attempt, knowing that there's always going to be some amount of bias, is to be aware of that and to sniff it out and to reduce it wherever possible.

S: Right.

C: That is a journalistic ethic. It's to report what is without saying how it should be, without saying how I want it to be, without saying how I like it to be. This just is.

S: Yeah, well, what we do would go in the opinion section of newspapers.

C: Exactly. We would be op-eds. And a lot of SciComm is op-ed.

S: It's op-ed. It's analysis, right? We're giving an analysis and opinion. And that's fine, you know what I mean? Because we're trying to help people make sense of the science, putting it into perspective.

C: And the thing is, we're not dishonest about it.

S: No, that does not necessarily imply dishonesty or deception or whatever. It is framing. It is saying, what's the context of the communication? Who am I talking to? What am I trying to convey? And then accurately portraying the science while putting it into some kind of meaningful perspective. And that meaningful perspective is the framing.

C: And we say we are pro-scientific skepticism. That is the goal here.

S: We are trying to expose cons and pseudoscience, not just talk about it neutrally like an observer from another planet. You know what I mean? Absolutely. And so I've like I've written about framing over the years on many topics, like with GMOs, right? So there's like this pure scientific question about what is the technology, what is genetic engineering, what does the evidence say. But we could also frame a discussion around GMOs from a perspective of how should the government regulate it, or what is the behavior of corporations who use GMOs, or what is the pseudoscientific claims surrounding GMOs, the conspiracy theories, etc. You know what I mean? So those framings are all part of the overall GMO phenomenon and you can't just say here's the dry science in complete absence of any context about the conspiracy theories about it or the actually anti-GMO agenda-driven communication that's out there about it.

C: This is so funny, Steve. I just got a text back from my friend. I said, do you guys avoid words like climate crisis when you write policy? Like, do you tend to avoid emotional language because it's more biased? Or do you use it because it's more motivating? We're talking about this on SGU right now. And she responded directly to, do you guys avoid words like climate crisis when you write policy? And she goes, oh my God, I'm laughing because I literally just told one of our clients that they need to do this.

S: They need to avoid it. Yeah.

C: They need to avoid using words like climate crisis when they're drafting policy.

S: Yeah, exactly.

B: That makes sense.

S: There is a darker side to framing, too. Well, first of all, there's a technical side to it. So for example, when we talk about framing, you could be talking about a little detail. Like for example, this is sort of the classic example from literature. If a surgeon tells a patient that the surgical procedure they're recommending has a 98% survival rate, The person is much more likely to agree to the procedure than if you say it has a 2% fatality rate, even though that's exactly the same information. So that's sort of that technical framing about how you convey information and do you say it from a positive perspective or a negative perspective. But then there's also political framing, which I think is what people reacted to, because that is inherently like spin and deception. Like when you say, when you refer to the inheritance tax as a death tax, that's a political framing. You know, that is meant to...

C: Oh yeah, Medicare for all...

S: If you talk about, like a hospital ethics committee, if you label it a death panel, that's a framing that's inherently, I think, deceptive, right? So you can use, like a lot of things, you can use it for good or you can use it for evil. But otherwise, it's just a tool of communication. So for example, you can use framing to rig any discussion or debate by baking in assumptions that favor your conclusion, right? You could essentially frame a topic in such a way that your conclusion is baked into the discussion. And that, of course, is an inherently deceptive use of framing. You have to sort of you have to challenge the framing. You can't just have a conversation within that framing. You know what I mean?

C: I mean, it's also like a logical fallacy. So it's like you're using framing to the extent. Yeah.

S: To make a circular argument almost.

C: Yeah.

E: Sounds inescapable.

S: Well, yeah, we always frame everything. That's the thing. It's like you're always doing philosophy, whether you know it or not. You know what I mean? There is some inherent assumptions about knowledge and facts and whatever and the universe in any discussion that you're having. But it's better to be consciously aware of that and the implications of it. Same thing, you're constantly framing your discussion in some context, either whether you explicitly know it and express it or not. And when you consciously frame a subject, you should be doing it to optimize understanding and communication while being fair and accurate and scientific. But of course, people will use framing to be deceptive and persuasive, to sell you stuff and to get your vote and whatever, to make you afraid, absolutely.

C: And the truth is, it's deeply disingenuous if you actively work as a science communicator, or identify as a science communicator if your job is to do journalism, if your job is to do communications. It's deeply disingenuous to not be aware of this.

S: Right.

C: Like you have to be explicit about it. I have to say real quick before you wrap it up. She added a little bit to the text thread, which I think is just so fascinating. She said, we don't avoid the word climate, but we lean into language like strengthen coastal resilience, mitigate climate impacts, et cetera, that talk about specific issues that climate has for communities, ecosystems, and industries. It's boring, but it's just less alienating and gets less of a reaction.

S: Yeah.

C: Truth is most people are on board at this point that climate change is real, but they just get their heckles up when we talk about it as a crisis.

S: Right.

C: Fascinating.

S: And climate justice, forget about it. So I think you would think justice, isn't justice for all, isn't this like an American concept? But the word has so much baggage on it. And I think what the specific baggage is, is that people have been convinced that justice is a zero-sum game. And that if one person's justice is at the expense of injustice to somebody else, and again, that's a framing, right? So the whole concept of justice has been framed in this zero-sum way, which makes it have this psychological baggage. Whereas that wasn't true historically, justice was like Superman, right? Truth, justice, and the American way.

E: Yeah, something everyone could agree on. Most people could agree.

S: Right. Right. But now it's been made divisive because it's been framed as a zero sum game.

E: Well, we saw this with the word skeptic as well over our 20 years of doing this plus.

S: Right.

C: Well, and to me, climate justice, and maybe this is my own bias or my own framing, is not the same thing as climate science.

S: No.

C: It's also not the same thing as a climate crisis or climate change. Climate justice is decision-making.

S: It's inherently political.

C: It's inherently political. It's saying climate change affects different people disproportionately, and we want to mitigate those effects. That's wildly different than just saying climate change exists.

S: It's happening, right?

C: Yeah, yeah.

S: All right.

News Item #5 - Promoting Homeopathy (1:14:28)

S: Evan, you're going to give us that promised discussion of homeopathy.

E: Oh yes, yes. And I'm going to give it to you from, well, where I found it, because it came creeping across my feed recently, anytime homeopathy in the news does. A magazine called Health. I don't know if you guys remember Health magazine, seeing it on the rack in the supermarket or wherever, right? Found it in 1981. Back then it was called In Health. And this magazine focuses primarily on women's health. Common topics include improper diet, dealing with life issues such as weak relationships and growing stress, not to mention latest fashion and exclusive beauty tips, various healthy food recipes, and other related articles that encourage people to be happy and healthy. Okay. Yeah, magazine was around for a long time, still is, only it's all digital now. They made that switch over in February of 2022. They ended the print publication and it is digital, ones and zeros all the way. Now we get to enjoy the website called health.com. That's a pretty nice domain name to have if you can secure it, and they did. But, as you know, we can't judge a book by its cover, and you can't judge a magazine by its title or the pretty faces on it. And even less so when your magazine is now 100% online, where a person might think a website called health.com might be a reliable source of good health information. In fact, there's a news rating site called NewsGuard. They rated the publication as reliable. Noting that it generally avoids deceptive headlines and does not repeatedly publish false content. Now this sets up the background for this news item. Headline reads, everything you need to know about homeopathy and its safety, courtesy of Health.com. Okay. I am sure as we delve into this article, I mean, this article, homeopathy and its safety, it is going to warn the reader about homeopathy, right? It's going to explain about the dubious nature of the claim. Like cures like. You know, where a molecule of something that makes you sick can be diluted out of existence and yet magically its memory will remain to cure what's bad for you. And the article I'm sure is going to speak to the implausibility of the suggested mechanisms that define all of homeopathy. And I'm sure they're going to warn their readers about homeopathy can only delay legitimate treatments that actually work helping sick people.

B: I'm sure.

E: This was written by a registered nurse, RN, Sarah Jividen, J-I-V-I-D-E-N. Sorry if I mispronounced that. It was medically reviewed by Arno Kroener with the letters D-A-O-M. Steve, you're MD, right? That's your, and Cara, your PhD?

C: Mm-hmm.

E: Okay. Do you ever heard of D-A-O-M for letters?

C: I know what D-O is.

E: Well, a D-A-O-M is a doctorate of acupuncture and oriental medicine.

C: Oh, no.

B: Oh, boy.

E: Described as a degree program that combines traditional Chinese medicine and biomedical concepts. Okay, so there's your medical review. Here we go. Homeopathy, a holistic medical practice that involves treating people with highly diluted substances to trigger the body's natural healing responses. It was developed in the late 18th century by German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Homeopathy is based on the principle of like cures like, meaning a substance causing symptoms in a healthy person can, in minute amounts, treat similar symptoms in a sick person. People might consider homeopathy as an alternative or complementary therapy due to its individualized approach and the belief that it stimulates the body's own healing processes. Its effectiveness is a subject of ongoing debate and research.

S: That's the framing.

E: Right, here we go. We're about to talk about some things that we just talked about again. Homeopathy, its approach is based on two unconventional theories. At least the unconventional got in there, finally.

S: But unconventional is not even accurate. Again, that's horrible framing. They're pseudo-scientific principles. They are magical principles, not unconventional.

E: Right. And Steve, you've got to take your red pen to this and cross out the words and write in the correct ones here. The law of similars and the law of infinitesimals, right? Those nice little theories.

B: Say that again. Infinitesimals.

S: Infinitesimals.

E: Infinitesimals. The law of infinitesimals. Yes. So first, the law of similars, right? Well, like cures like. A substance that causes symptoms in a healthy person can be used to treat similar symptoms in a sick person. Yep. And then the second law, extreme dilutions of substances. The belief that the more a substance is diluted, the more potent it becomes. How? These delusions often reach a point where no molecules of the original substance remain. It is believed that the solution retains a quote, memory of the substance. Yes, that magical memory again. And homeopathic treatments are highly personalized. Did you know that? Practitioners consider a person's physical, emotional, and psychological state to choose the most appropriate remedy. Doctors never do that. Some people with the same condition receive different treatments. Homeopathy abuse symptoms as expressions of the body's attempt to heal itself and treat the individual as a whole rather than focusing solely on the disease. Steve, you only focus on the disease, okay? You do not treat the individual as a whole, right?

C: How dare you.

E: How dare you do this? And then they talk about the various things that it can be made from, in a sense, or extracted from. But we won't go over that. They kind of just give you a list of the things. Now, here's what they do start talking about. What is it good for? Some studies and clinical trials suggest that homeopathy may be helpful or provide symptom relief for certain conditions, such as childhood diarrhea, adults, you're out of luck, ear infections, asthma, menopausal symptoms, sore muscles, colds and flu, allergies, but it might also help reduce symptoms of mental health conditions such as Major Depressive Disorder, MDD, and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, PDD. I'm surprised it's probably an even longer list than all these things in reality, is what they claim. Now we get to research and evidence. Critics argue the benefits of homeopathy are primarily due to the placebo effect. I don't even know if that's right. Don't the major-

C: Yeah, like there are no benefits.

S: Yeah, by saying the benefits, the next line is any therapeutic effects. There are no therapeutic effects.

E: Right.

C: If there are any quote therapeutic effects, yeah, you're right. There are no therapeutic effects. It's all non-therapeutic effects.

S: It's all symptomatic and it's all placebo.