SGU Episode 816

| This episode needs: proofreading, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 816 |

|---|

| February 27th 2021 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

What is the capital of North Dakota? |

Groucho Marx |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Tuesday, February 23rd, 2021, and this is your host, Stephen Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody.

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey, guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening, everyone.

S: So it's finally warming up in Texas. We touched a little bit on the energy woes, the electricity woes that we're having there. Last week's show, but now we've had a full week for the whole story to unfold.

J: Steve, before we get into the details, can we just say, listen everyone in Texas, it was really a hard thing to watch. We had our friend on that lives there. It was scary. It was horrible for so many people. And anything that we say is not judging the people that went through that. We're going to chit chat today about what went wrong in Texas, but we're in no way pointing fingers at citizens who suffered in all this.

C: Oh, they're the victims for sure.

S: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So here's the interesting bit of misinformation that's going around. So immediately people start pushing their political agenda, right? Because that's what people do.

E: That's what they do.

S: Yeah. So the Republicans were blaming the wind turbines. They said that they were freezing up and that's why there was the rolling blackouts and there was the basically the electrical grid was failing. And that's nonsense. The quick story is there's three electrical grids in the United States in the lower 48, I should say. There's the Eastern grid, the Western grid and Texas. Texas is its own grid. It did that specifically to avoid regulations on selling electricity across state lines.

B: Imperial entanglements.

C: Well, and by the way, not all of Texas. El Paso happens to be slivered into the Western grid. And just-

S: Oh, is that right?

C: Yeah. So compare how El Paso did. They didn't lose power.

E: Well, yeah, you can't really compare it.

S: If you get into a problem, you could buy electricity from another neighbouring state. That's kind of the bigger the grid, the better. And the more renewables we have in the system, we want the grids to be even bigger. We may need to connect the Eastern and Western grids. And if we really want to maximize renewable, because over capacity is one of the ways that you deal with the intermittent nature of it. But in any case, Texas is its own grid. And they also have a very, very deregulated system. So what that meant practically was that the energy companies were not required to winterize their facilities. So they didn't, even though they had some like a cold snap 10 years ago with-

B: 2011. Yeah.

C: And with hearings saying we need to ensure that this never happens again, you guys need to winterize your equipment. And they were like, no.

S: And they didn't. It was voluntary. So they chose not to spend money to do it. And they did that to keep their prices down, partly, inevitably we got it. It happened again. And so it wasn't just the wind turbines. Every single energy source failed, coal, natural gas, nuclear-

B: Fusion, all of it.

C: I mean, I saw some-

E: Perpetual motion machines were stopping.

C: I saw some officials from the actual energy companies saying we were literally days, maybe even hours away from a blackout that could have lasted months.

B: Months? Can you imagine that?

S: They said minutes, maybe seconds is what they actually said.

C: Minutes, maybe seconds?

J: But wait, what does that mean? What was happening? Like, Cara, what was the situation that would have made it a lot worse?

C: They were close.

S: So this is the problem. When part of the electrical grid goes down because it fails, then other parts have to kick in to take over, then they overload. So they shut down to keep from overloading. And so it's this cascading shutdown across the grid. That's what happened.

C: Which is why they do intentional rolling brownouts and blackouts on purpose to try and relieve the pressure off the grid.

'B: Plus, it wasn't so much rolling, though, was it?

S: They did it right before the grid failed in a way that would have caused damage that would have taken a long time to repair. So they just barely avoided that. They did that with rolling blackouts. And then there were actual blackouts when, again, you have that cascading failure.

B: Yeah, but the other angle there, Steve, is some of those rolling blackouts weren't rolling at all because it's like the wealthy communities had it all the time and the not so wealthy communities didn't.

C: Really? Is that documented?

B: That's what I read.

S: So what happened was they spared critical infrastructure like hospitals. Where do you think the hospitals are located? So the neighbourhoods that had – and again, it's totally reasonable to not cut power to a hospital, but they couldn't just pick out the hospital. They had to spare the entire neighbourhood. And so that difference, like the wealthy versus the poor neighbourhoods, had to do with that's where the hospitals were, you know. But that was the end result was, yes, some of the more wealthy neighbourhoods were spared, the rolling blackouts. But there were actually permanent blackouts in some locations for days caused by just the overload. Because the thing is, no matter – remember, with coal, natural gas, and nuclear, they all ultimately do the same thing. They make steam and they turn the turbine. And it was those components, the moving the water around, that froze because they didn't have heaters on them. And the other thing is we have wind turbines in New England. They don't freeze here because we have heaters on them. They're just winterized.

C: They're winterized, yeah.

S: So the problem was that all of the energy production modalities were not winterized. To pick out wind turbines and say they failed and they were the problem is pure nonsense. That is just political propaganda.

C: The first problem was that their grid, which they is unregulated and is privately owned was not winterized. The second problem, and with that all the other problems we talked about, not being able to borrow energy from other parts of the country, not being able to distribute the need. So the second problem is that on this unregulated market in Texas, people are allowed to sell wholesale energy. They're allowed to sell variable weight wholesale energy. And unfortunately, that also disproportionately affects poorer people because the rates are significantly lower. They come with a greater risk, but they're more affordable in the day to day. And since Texas, by and large, doesn't deal with this, except it just did 10 years ago, basically, most everyday people think I'm going to look at these rates, they are significantly lower if I take a variable rate because usually we're not in the hot box or the cold box as it were. Unfortunately, there was no mechanism in place. So when like one particular, I read a deep dive about one particular variable rate company called Gritty who buys wholesale and sells off directly to the customer. They actually saw what was happening, basically the bubble bursting right in front of them. And they frantically reached out to their customers saying, you need to dump us now. If you don't dump us now and get with a flat rate energy company within the next day or two, you're going to be hit with bills that are thousands of dollars, 15,000.

B: That was actually nice of them to actually do that.

C: Because ultimately they're unregulated. They're doing what the market allows them to do as a business, whether you want to say an ethical practice or not is a point, but it's beside this point. Ultimately, when they saw that this had a terrible backlash effect for themselves and for their customers, they were like, we don't have any safeties in place. The only way to avoid getting hit with a $15,000 electric bill is to dump out now. But what are you going to do? They're going to be able to call and wait on hold with the electric company in the middle of this blackout. So many people didn't get the option.

B: Worth a shot.

C: Yeah, exactly. It was worth the shot.

S: They could email for two days.

C: Exactly, because they didn't either have electricity or they were too busy trying to like board up their windows.

S: Yeah. I mean, some people have described, though, the wholesale market as predatory and that seems to be reasonable because they acted the same way that like variable rate mortgages were predatory.

C: Absolutely.

S: Up front, it sounds great. You get this low rate, but the thing is by getting the cheap upfront wholesale electricity, you're basically not paying for insurance, right?

C: Absolutely.

S: It's really cheap to drive without insurance because you get into an accident and then the other person gets screwed, not just you. So in this case, the federal government's having to bail out Texas.

C: Yeah, because Texas themselves didn't regulate. And this is the part that pisses me off because who keeps winning in these schemes? The people who keep getting money regardless of what they do to protect the consumers. And that's why this story makes me angry because what we're talking about here is not a luxury item. We're talking about a necessity to live. Electricity keeps people alive.

S: Well, that's what creates perverse incentives, right? The system exists so that people can take a risk to make a lot of money. But if the risk bites them, they ask somebody else pays for it. That's what we call the perverse incentive. That's a setup for for bad stuff to happen.

C: So that's why regulation exists.

S: Yeah, but I don't mind free market solutions and having the free market. That's great. I think you need to balance that with regulations, obviously, but you can't build in perverse incentives where it's a win-win that the investors make all the money and they never lose because they get bailed out because of whatever. They're critical or they $10,000 bills to their customers and the customers need to get bailed out.

C: Well, and that's a classic example of the freest of free markets. That's the problem. When you really look at laissez-faire economics, what you're saying is any time there's a demand we're going to because supply is low and the demand increases, the costs are going to shift.

E: Like when that guy, Scavelli, whatever that scumbag was, raised the price to thousands of dollars for that medicine.

C: Yeah, but even that's a slightly different example because in this case, the algorithm was set in advance.

S: And we knew this was going to happen.

C: We knew this was going to happen and they weren't price fixing. They were doing the opposite. They were saying, no matter what, we're never going to cap. And so ultimately, without a cap, the free market was doing exactly what it was designed to do, which is to basically enable or enact these perverse incentives and put all the burden on the consumer so that the people at the very, very top made their money anyway. And then when there was still a problem, a regulatory problem, what ends up happening? The federal government, so our federal taxes, end up paying off the place where the state taxes aren't being collected. And that's frustrating.

B: Yeah, that really sucks.

S: And the bottom line is it was the lack of winterizing because nobody wanted to spend the money to invest in it. That was the ultimate problem. The thing is, it's so fixable.

C: And prevention is so much cheaper. It's so much cheaper.

S: You need to be living in the real world.

E: I wonder if the public pressure now will be on to do this and they'll finally get their acts together.

B: Well, why? Why would the pressure be on? Because next time it happens, then everyone else's taxes will pay for this to bail them out again, right?

C: Well, I think it's because people died. There's a certain point where money doesn't even matter anymore when people's lives are on the line.

B: Well, I think the jury's out whether we cross that line in terms of what these people do. I mean, you know how people are. The weather's in the 70s. People are going to forget about this and move to the next thing. And then in 10 years or five years or next month, it's going to happen again.

C: Gosh, I hope not.

S: Well, that's the other question is nobody knows the answer to this is what's the relationship between events like this, like this ridiculously cold weather in Texas and global warming, extreme weather events like this, are they going to be coming more frequently?

B: Definitely.

S: Yeah, I mean, it seems that way. It seems that way. I don't know that that we have enough evidence yet to say for sure, but it certainly is plausible that we might be seeing more extreme events like this. We certainly can no longer be confident that past experience is going to predict future experience.

B: But that's what the science predicts more extreme weather events.

S: It's true.

C: But pointing to you're right, pointing to a specific example, my hope is just that individuals within their communities organize. That people who had to put up with this and who were, damaged, some of whom irreparably, some of whom lost limb or life, see this as something that's beyond the pale, because they're the only way that change is going to be affected is if pressure is put on by the constituents, it's the only way you're going to see change.

S: Yeah, totally. OK, let's move on.

What’s the Word? (12:45)

- Word_Topic_Concept[v 1]

_consider_using_block_quotes_for_emails_read_aloud_in_this_segment_

S: Cara, you're going to do a What's The Word this week.

C: I am. So this word was recommended or suggested by Michael Viau. Hopefully I'm pronouncing that right from St. Louis. He said, "I work in electromagnetic compatibility and came across this word when researching lightning formation. The word is percolation. This is the fun one for the whole team specifically because it can be tied to fractals and coffee." It's it's all of our buttons. "Percolation theory or my profession's application of it, at least, is a statistical way of modeling current paths through composites made up of various materials with different properties." And I was like, what is that? So I started to to reach research a little bit more. And what I love, oh, the title of his email was What's the word? I've got a fun one because I say that every week. I got a fun one. OK, so percolation. When we think of the word percolation, maybe we should do this backward and look at the etymology first.

E: Shun. Yes, you said work. Look at it backwards.

C: Gosh, it's too dense.

E: I thought you were going to get it.

C: Do you notice that I probably laugh more, Evan, when it's somebody else's story and you do one of your funny Evan jokes because I'm not as invested in like, what am I going to say next? What is the depth of this? I don't want to screw this up.

E: That's right. Yeah.

C: That's funny.

E: Otherwise, I'm throwing you off your game.

S: As the one who edits the show, I can tell you that Cara and Evan giggle at every joke and Bob and Jay do not.

E: Someone has to.

S: Everything funny in the show.

B: For the record, Jay and I laugh at the good ones.

E: Yes. Yeah, Bob, you're selective.

C: Evan and I just we just humor is an important part of our life. That's all.

J: I mean, yeah, I mean, it's good to wear rose coloured glasses because you're just happier. Life is pain, man.

C: Life is pain. We see the absurdity and the suffering. Welcome to my existential world, Jay. All right. So percolation. The PIE of the first root, the Proto Indo-European root, per means forward. And in this case, they're kind of taking that as through. And then colade, this is an interesting suffix in that we don't really know where it came from, but we do know that the whole word together, percolationum, came from the Latin. And so the colade part translates to strain. So it comes from colum, which is a strainer or like a sieve. So to percolate is to strain through, to sieve through. And that's really what the word means, right? That's the usage that we're all used to. If something percolates through something, it's moving through a permeable substance. Sometimes it's to extract the solute out of it. Sometimes it's to take just the liquid component out of it. So with coffee, we're percolating through, but we're just keeping the water that has had the coffee grounds percolated. We're not keeping the grinds, we're throwing those away. In other cases, we're percolating something in order to pull out the solute. Does that make sense? It's like diffusion.

E: Yeah.

C: Yeah.

E: Jay, remember when we were building my house in Oxford and the surveyor went out there and did the PERC test on the land to measure how fast the land would absorb water?

C: Yeah. And so you will see that. You'll see the word used more specifically in like engineering, surveying, geology. You'll see percolation through rock, through soil. You also will see it in a more literary sense, right? This idea is percolating right now, just letting it kind of simmer, letting it sort of move through my brain juices and eventually it's going to settle. So that's kind of the typical term that we use. But of course, my interest was piqued by Michael when he talked about percolation theory. So I started to do some deep dives. It's complicated, very complicated. And it does have to do with fractal geometry. It also has to do with statistical physics and math. We see it in material science. We even see it in like network theories. So the best way that I found for somebody to describe percolation was talking about, a piece of foam, for example, or really any somewhat porous structure. Let's say a big chunk of terracotta. If I was to pour water on top of a piece of terracotta, how would I calculate where the water would end up as it's seeping through? What would its path be? Because they're all these little random holes. So we don't have perfect nodes. We don't have perfect links. What we have is this porous substrate that's random. So this is a theory that uses these different structures to try and describe phenomena passing through in this random graph. And it's fascinating as you start to dig deep and you start to see all of these little schematics of percolation theory. You can see representations of percolation theory using these really complicated and beautiful graphs. And so in a way, not even in a way, pretty directly, it relates back to that route beautifully. But if you didn't know what percolation theory is, your head might not go to that place. So I guess Michael's profession, which he didn't say what it is, they use percolation theory to model current paths through composites made up of various materials with different properties. So he may be in more of a material science or engineering example of that, but you also see the modeling used kind of more theoretically. You might see it used in fractal geometry. You might see it used more in other versions of mathematics where there is no actual substrate, but instead we're modeling what would happen with a random substrate. And it's fascinating. So thank you for the opportunity, Michael, for me to dig into percolation theory and to percolate a little bit on this fun word.

S: Yeah, like when you think you know what a word means, but it really has so many more meanings.

C: Mm hmm. Very cool. And in this case, it's really fun because it's one of those words where the root stays there. You know how sometimes we're like, okay, this word is used here, here, here, and I still can't figure out why this is the word that this field shows to describe this phenomenon. But in this case, it all comes right back to that beautiful root of basically putting something through a sieve of something moving through pores.

S: And the etymology is highly conserved.

C: It is. I am saying that.

J: Cara, do you ever think of all the animals that can fly, the fly got the name?

C: You're right.

J: Why would they give the most insignificant thing that flies, like that and a gnat, you know? But why would they? There should be a giant bird called the fly, you know what I mean?

C: No, I like that it's such a little one. I like that because then everything else would be the fuzzy fly or the beaked fly. See, why didn't we do that? That's the question. There are more kinds of flies. I mean, there are a lot of flies, but they're all flies. They're not a lot of different things that fly.

B: Why don't they call a flying squirrel a glide?

J: It's not flying, it's gliding.

C: There are sugar gliders.

E: Sugar gliders?

C: Yeah, they're related to flying squirrels.

J: They're little bats.

C: No, sugar gliders aren't bats. They're mammals.

J: No, you're right. They're little, I'm sorry, they're little, like they're little guys. They're like squirrels.

S: Why don't they call bats flappies?

C: They should.

S: Inexplicable.

C: Snakes, danger noodles, and raccoons, trash pandas. What are some of the other ones? I love them.

E: Whistle pigs, yeah.

News Items

Perseverance (20:52)

S: All right, Jay, tell us all about the Perseverance.

C: Yay, not the perseverance, which so many people have said I've spoiled them.

J: You know, science has completely kicked ass. It has for a very long time, but this mission has really impressed the hell out of me with everything. Once you start reading about what was achieved here. The Mars rover mission that we just saw, it's called the Mars 2020, and this rover mission by NASA's Mars Exploration Program is a mission that was originally announced back in 2012, and it includes or included three major components. So, there's the cruise stage that was used to travel between Earth and Mars. There's the entry, descent, and landing system, EDLS, that includes the aeroshell descent vehicle and heat shield. And then we have the sky crane that was needed to deliver Perseverance and Ingenuity safely to the surface. And just so you know, the Ingenuity is the test helicopter. I'll give you a little bit of information about it in a minute. So, Mars 2020 mission, this was launched on an Atlas V launch vehicle. It took six months to reach Mars, and it landed just a few days ago, February 18th, 2021. So, the Perseverance rover has a slate of missions, primary objectives that I'll list off to you. This is exactly what NASA had on their website. It's to explore a geologically diverse landing site, assess ancient habitability. And they do this, and this is me talking, by investigating its surface, the geological processes and the geological history. And when they're saying assess ancient habitability, they're talking about did things live there previously and what was the previous habitat? Seek signs of ancient life. They wanted, they're looking for these things and rocks and different places that they would expect there to be signs of life. That's where the rover is going to be looking. Gather rock and soil samples. This is amazing. So this is going to be, the rover is going to be gathering soil samples, putting them into a test tube and leaving them on the surface of Mars for a later pickup mission, which I'll tell you about, and demonstrate technology for future robotic and human exploration. So let me get into some details here. The rover is gathering samples on the Mars regolith, right? Does that sound sexy? It's cool, but let me tell you the sexy. The samples are going to be stored in tubes and then it's literally going to leave them on the ground as it rolls through its path. So it's going to leave a path of tubes behind it. Perseverance can't pick up the samples once it puts them down. And eventually though, the goal is to return these samples back to earth. And this mission, and I have to do a side step here and just quickly tell you about this mission. It's scheduled in 2026 and the preparation of the samples is a key part of the Perseverance mission because in 2026 we're sending something called the sample retrieval lander. And like I said, it's slated to leave earth in 2026 and it will be picking up the samples on the sample fetch rover. It's going to be like a little dog that runs around. They know exactly where the samples are with satellite information and they're measuring distances between objects and they're calculating exactly where they are. The rover is going to go pick them up. It's going to be designed and built by the European Space Agency. And then that rover is going to deliver them to another thing that's going to shoot it like a soccer ball with all the samples stuck into it. It's going to shoot up out to another thing that's going to send it back to Earth. So that mission is really cool. I'm dying to read all the details about that.

B: Wait, how is it actually lifting off of Mars to send it back to earth?

J: That soccer ball payload gets put on a little spaceship that launches it back into orbit and then another thing takes it home.

B: That sounds like that'll be the very first thing launched off of Mars then, right?

J: It's going to be the first thing that is bringing back samples from Mars. Absolutely.

B: Something has to land and then take off again.

J: That's right. You're right, Bob.

B: That's a big deal.

J: Perseverance is also responsible for scoping out the landing site for the next phase of the sample return mission, which they're using it to find a really flat area. But they also, keep in mind, they want that sample return mission to be near where the rover is to pick up all the doodads. So it's going to land right in that vicinity again. So NASA designed the rover with its past rover Curiosity in mind, which was very smart because many of the components developed for Curiosity were used in Perseverance. So it was a very low cost way of reusing technology that has already been proven and they added only the things that needed to be added to help this mission achieve its goals. As an example, they added the core drill that takes samples and some new instrumentation. The rover has 19 video cameras and two microphones, which means they're ready to make rock and roll videos, which I think is awesome. The rover is also going to test technology in the Martian dust to see how it possibly could interfere with technology, right? They want to know, is this dust going to get into stuff and do nasty things? Because we know that the moon has a really nasty sharp edged regolith. So they want to know like, okay, what is this Martian terrain going to do and what's the dust like? Is it dangerous? Perseverance will also test technology and this, I think this is the one that really blew my mind the most. They'll take Martian carbon dioxide and do what, guys? What do you think they're going to do with it?

B: Smoke it?

E: Martian carbon dioxide.

S: Make oxygen out of it.

J: Right. They're making pure oxygen out of it. And what is pure oxygen good for? It's good for-

B: Breathing and for rockets.

J: Exactly. Oxygen is one of those things you could use it in so many different ways, but the two main things is it's for rocket fuel and for people to breathe. So that's awesome. So I guess in the future, they're going to put instrumentation out there and machinery that could slowly process oxygen, which is great. Just pull it out of the CO2 that's in the atmosphere. The rover is also going to try to find subsurface water or at least prove that it's there. Improve future landing techniques and study the weather. And in particular, they want to know what's in the air. They want to know what particulate makes up the air. This information is vital to send actually people there and other robots. So this will help them determine how they need to build habitats. It'll determine how they will need to build future technology, other robots and things like that. Another interesting upgrade in the mission is a guidance and control system called the terrain relative navigation. So if you watched Perseverance get deployed by the sky crane, you may have noticed that it made some lateral movements to find better land, to find a better landing site. So the new system allowed the sky crane to change its heading during the last moments of the landing process. And past missions didn't have this. And what happened in one of the past missions, they landed in a bad place that was suboptimal. And that's bad because you have all of this money, all these people, all this human effort and you land in a crater and you're kind of screwed.

B: Wouldn't water be suboptimal?

J: Absolutely, Bob.

E: Sub-aquatic.

J: Yeah, they're building rovers, not boats. Of course, they don't want to land in a mushy area.

E: Not much chance of that on Mars.

B: Water would be optimal for a sub, so it would be suboptimal.

J: Oh, you idiot. Oh my God.

E: Yeah, Bob was doing the fun.

J: I will move on, Steve.

C: I liked it.

S: That's a thinker.

C: Yeah, jokes are extra funny when they're explained.

B: Just move on, just move on.

J: Bob, the little helicopter, please let me talk about this guy. He deserves a little love. So, he's a little robotic helicopter, ingenuity, and he will test or she will test powered flight in Mars' extremely thin atmosphere. It's a big deal, guys.

C: Wait, is she a helicopter or is she like a drone?

J: Well, they're calling it a robotic helicopter because I don't want to talk about stuff I'm not an expert on. Like, what's the difference between a helicopter and a drone? I think it's...

C: Well, helicopters are piloted, usually.

J: I think it has to do with the blades.

S: A self-flying helicopter.

C: Okay. That's a good one.

J: All right, so this little guy is going to be used to be first, it's going to be the first thing that has ever flown on an alien planet and it has five planned flights. Each of them is going to last about 90 seconds. It'll go up about three to five meters. In those three to five meters as it goes up, it's going to be flying around, of course, and man, I'm hoping that it has a couple of cameras on it. It's got to have a camera.

E: It better.

C: It would bum me out if they didn't stick a GoPro on there.

J: Yeah, but at least Perseverance will be shooting it. We'll see what it does. But it's going to take off, it's going to fly around, it's going to do some manoeuvring, it's going to land, and what are they going to find out? How much energy did it take? Did the atmosphere interfere or play nice with the way they designed the blades? Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. They're going to do all these things that are going to tell us awesome information. So when we want to put a real flying machine down on that planet, we'll know how to build it. Now, one last thing. I thought this was really, really cool. If you look at the parachute that was used to slow down the sky crane and rover on the descent, it had a secret message encoded in it. The parachute had a series of red and white stripes that were put in a pattern that was some internet users, air quotes, internet users discovered the hidden message. It was written in binary language, which is a computer language, and once they decoded it, it said...

B: Send more Chuck Berry.

J: Of course. You know, anybody that watched SNL back in the 70s knows that one. No, it said, dare mighty things, and this happens to be a key phrase at NASA's JPL.

B: That's awesome. I love it.

J: So somebody sat around and said, hey, I know you guys are working on the super important stuff, but let's not forget that we've got to send some humanity to Mars. Let's send a message along with the parachute that's sitting on the surface of Mars now and probably will be there for a very long time. It says, dare mighty things. I love that.

C: Didn't they do something similar with Curiosity where the wheels in Morse code said JPL?

J: I think you're right.

C: Yeah. It's like they couldn't be so overt by actually writing that, but they coded it, which makes it extra fun.

J: They totally should have put human footprint marks on the wheels as it rolled around.

B: Oh, my God.

E: Oh, great. Yeah, that's what we need.

J: Now, guys, of course, please do more reading. There's so much I left out. There's so much more detail to this. And read about that retrieval mission as well, because this is a really cool thing that they're doing. It's in the works. It's not like something they're cooking up. Like it's in the works. We're going to do it. And that at some point in the next six to eight years, I don't know how long it's going to take. Maybe it'll all happen in 2026. The whole mission might be resolved. We might have Martian regolith on Earth that we could study and do all the analysis that we need to to find out what it's made of. Is there microbes in it? I mean, think of these these samples that are being collected are important samples because the team at JPL is going to tell the rover when to take a sample.

S: Jay, this is the 46th mission to land something on Mars. Guess how many of them were complete failures out of 46?

C: I think they've only landed, like, eight things, right?

E: 30.

B: Could be a lot like in the 20s.

E: I think it's in the 30s.

C: Oh, there's so many failed missions.

S: There were 22 complete failures, two partial failures.

E: Oh, OK. So as bad as I thought.

S: So more than half.

J: So this utter success, you got to think about-

S: This is a complete success.

J: We have an incredible amount of data of what parts wore out and when on the previous rovers, right? And again, I remind you, the other rovers lasted way longer than they even intended, like remarkably longer. People were doing things with these rovers they never intended to do with them. So now we have a rover on there that landed without a hiccup. They have it, reinforced all the things that wore out on the other rovers. This thing's going to last a long time. They have a one-year plan for it. And then they go, yeah, and if it lasts longer than a year, you know it's going to last longer than a year. This thing is going to be kicking around for a long time.

S: Yeah, cool. All right. Thanks, Jay.

Communicating While Dreaming (33:18)

S: Bob, let me ask you a question. Do you think it's possible to communicate with somebody while they're dreaming?

B: I know it is.

E: Absolutely. Wake up. You're dreaming. Hey. There you go.

S: Without waking them up. Without waking them up.

E: Oh, oh, oh, oh, oh, oh.

C: Does it have to be verbal?

S: Yes. Your communication to them is verbal.

C: Oh, so not like putting their hand in warm water. See what happens.

E: I don't know if that counts as communication.

S: So this is an interesting question that researchers set out to answer. It tells us a lot about what the dreaming state actually is. Obviously, dreaming is something we all experience. Even if you don't remember your dreams, you dream. Everybody dreams. The dream state, as you know, is rapid eye movement or REM, REM sleep. We call it that because when you're dreaming, your brain stem basically paralyzes everything below the neck so you don't act out your dreams, right? But you can still move your eyes. You can still move your face a little bit. So your eyes are undergoing rapid movement while you're dreaming because that's one of the body parts that's not paralysed.

C: Unless you have certain parasomnias and then you do act out your dreams.

S: Yeah. People can, "sleepwalk". That's a parasomnia. It's something wrong with the wiring for sleep.

B: Yeah, but is sleepwalking happening during REM? I thought it was non-REM.

S: No, it's usually non-REM.

B: Yeah.

C: That's interesting. Yeah.

S: So did you know that you dream during other parts of sleep? Just not as much.

B: Really? So non-REM?

S: Yeah. Some dreaming happens in other stages of sleep. Yeah, non-REM stages of sleep. So what is happening in your brain when you're dreaming? If you look at an EEG, do you think you could tell the difference between somebody who's dreaming and awake?

B: Not easy. It's subtle. It's largely the same.

S: Yeah, it's almost the same.

C: Dreaming and awake? OK.

S: Dreaming and awake. Your brain is really active when you're dreaming, which makes sense. If you look at an fMRI, which is a little bit more detailed than an EEG, most of the brain is active.

C: What about other areas?

B: What about motor cortex? Yeah.

S: The motor cortex is active, but it's just being paralysed on the way down.

B: Okay. That makes sense.

C: So that's brainstem, right?

S: Yeah. All the sensory areas are being active. The only part of the brain that's less active is the frontal lobe, which kind of makes sense.

C: Makes sense, yeah. You're not really doing a lot of checking and balancing on yourself when you're asleep.

S: Yeah. There's not a lot of reality testing going on.

C: Yeah. Not a lot of inhibition.

B: Look at the talking elephant. Who cares?

S: Yeah. Right. Probably because if you were, you'd wake up. You'd realize you were dreaming. And then we've spoken many times on the show about lucid dreaming, which is a dreaming state when you have awareness of the fact that you're dreaming.

B: Yeah. It's pretty wicked.

S: This is a slightly different state than normal dreaming, obviously, because you have enough awareness to tell that you're dreaming. It's very unstable. You tend to either dream you wake up or actually wake up when one of those two things happens. Of course, you dream you wake up you lose your lucidity. You go back. You think you're awake, so now you don't know that you're dreaming. What the researchers did was they actually looked at people who can get into the lucid dreaming state. And there's things you could do to trigger that and to train yourself to make it more likely. And then while subjects were lucid dreaming, they tried to communicate with them. Previous researches have done this, but they've essentially relied upon the subject reporting what happened after they woke up.

C: Which is sort of like has all the same problems as like near-death experience.

B: But that's not true. But that's not true, because I know in the 80s, 1981, Stephen LaBeer relied on EEGs to detect eye movements as a method of communication. He used EMGs to catalog things like you could fist clench in your dream and you can create a detectable signal in an EMG. It's subtle because you're paralysed, but it's detectable. And they've also communicated over breathing. If you hold your breath or breathe rapidly in a lucid dream, that is detectable outside of a lucid dream. So this is one of the reasons why I'm very disappointed with this research on the verge of disgusted, because this was 40 years ago LaBeer was doing this. The only difference that I could tell is that this is now, oh, it's in real time. You don't have to look at an EEG and see what these people within a lucid dream were saying a few hours ago, or an hour ago, or 10 minutes ago. They're doing it in real time. Big whoop.

S: Yeah, but that is exactly the incremental thing that they're doing.

B: A 40-year incremental leap. Wow, good job, guys.

S: I think it's a little bit more than what you're saying.

B: Bring it then, tell me.

S: It's not just that the person who's lucid dreaming is communicating out.

B: I'm telling you. I'm telling you that's what they were doing. They figured out a way to communicate.

S: Hang on. It's what they demonstrated. You tell me if they did this 40 years ago, and maybe they did. I don't know.

B: They sent messages. Go ahead.

S: Well, it's not just sending messages out. They were able to respond to the information that was being given to them while they were lucid dreaming. My understanding is that's the new bit.

B: Yes, that's the new bit.

C: So it's not just while you're asleep, make sure you clench your fist really hard.

B: No, no. Yeah, that's it. It's responding.

S: While you're lucid dreaming, it's not just responding. When they ask you a question, you have to understand the question. You have to formulate an answer and then communicate your answer back to me.

B: Yes. And that is an incremental advance. But 40 years ago, they were agreeing, okay, when you recognize you're lucid, you do this pattern of saccades with your eye so that we could see it in your EEG. You go left, right, left, left, right. And then that will mean you started lucid dreaming. And then they had a lucid dream. They remembered what they planned to do and they did it. And then they read that back out in the EEG or the EMG. So yes, it's an improvement. My beef is that after 40 years, this is all we got.

S: I get it. It took 40 years to do this. They could have done it 40 years ago. But this is different. This means, though, that while lucid dreaming, you can hear, understand, and absorb something somebody is saying. That's new, Bob.

B: I'm not surprised at all. I'm not surprised at all.

C: Did you guys both say earlier that lucid dreaming and the alert awake state are imperceptibly different on scans?

B: Yeah, looking at scans. They're very, very similar.

C: How do you know the person's actually asleep?

B: We all dream. We all dream. Some of us lucid dream. If you're a lucid dreamer, you know when you're lucid dreaming. I mean, they're not going to be fooling themselves, that's for sure. If they're charlatans and they're trying to trick the researchers, then yeah, that's possible. But that's so remote. I don't even think it's a word to consider.

C: Sorry. The subjects in this study are known and self-described lucid dreamers. They're not just people who were in REM. Oh, that's a different thing.

B: Yeah, if you're going to do research on lucid dreaming, you almost have to get someone who has some facility with lucid dreaming. Otherwise, you'd be waiting a month for a lucid dream.

C: To be clear, I know that's your area of interest, Bob. I wasn't sure that the study had anything to do with lucid dreaming. It sounded to me like the study was just, can people hear and respond even when they're asleep?

S: But it was on people who were in the lucid dreams.

C: Okay, sorry. That wasn't clear to me. You probably did make it clear.

S: I said it. I said it. You just missed it.

C: Okay. Because that would be a massive problem with their study. You'd need to make sure people were actually asleep.

S: Yeah, but also they're doing EEGs on the people. They're making sure they know what sleep stage they're in, et cetera. This study was done by four different labs at the same time using slightly different methods.

C: That's pretty cool.

S: I like this. They basically did internal control. It was replicated four times before, and they all published together just to make it more robust. Because otherwise, you could ask a lot of questions about, was this a fluke? Was this somebody who was punking the researchers or whatever?

B: So it was good science, yes.

S: So scientifically, I liked that internal control thing. It was a little bit more robust. It does make you think about where theoretically this could go. Maybe we'll wait another 40 years, Bob, and do another incremental study. But for example, if we could figure out some way to really stabilize the lucid dreaming state, then could you...

B: That'd be awesome.

S: What kind of experience could you have at that point? Could it be like Inception where you have this hyper real movie adventure kind of lucid dreaming thing that lasts for hours? That would be...

C: Okay, here's the thing. I don't want to work or play or whatever that is that you're talking about doing while I'm asleep.

B: Then sit on a beach and drink a cocktail.

C: I want my brain to do what it needs to do while it's asleep. I don't want to tell it what to do.

E: Tom Hardy shows up.

B: I don't think you're shorting yourself on anything by lucid dreaming.

C: I don't think you know that yet, Bob. I don't think any of us know that yet.

S: Yeah, the question is, would that interfere with memory consolidation?

C: And maybe not even just memory consolidation, but the other restorative cellular properties, like all the things that happen during sleep. If we're forced to kind of...

S: That probably happens during the deeper stages of sleep.

C: Yeah, you're probably right.

S: This is the REM sleep when your brain is super active anyway. It's already almost as active as when you're awake.

C: I still wonder if there's some sort of mechanism by which the way that our dreams play out. As we know, they do aid in memory consolidation, but we still don't know how. And I wonder if interrupting that mechanism by giving it more order wouldn't be detrimental in some way.

S: Cara will do that study in 80 years.

C: Yeah, exactly. We don't know yet, which is why I might, in this specific case, use the precautionary principle. What I do know is that animals who are sleep deprived die horrific deaths.

B: This has nothing to do with sleep deprivation, because if you extend your REM, you will actually increase your sleep hygiene, I think. I mean, that's what you need, REMs. REM is what you need.

C: But we don't know yet if that's also true if you do it through induced dreams.

S: Yeah, if you have extended lucid REM though.

C: Yeah, I don't know. Is that restorative? Is that possible? I don't know.

B: My guess is that it would be, but I think we would know if we actually did more research in the past 40 years. We'd probably know that by now.

C: I do have to say, though, there's a part of me that is still highly, not skeptical of the results of these types of studies, because I think there's a lot of value and a lot of validity in them, but I still wear a skeptical hat when any study biases towards a very particular type of group that already does a lot of interesting brain stuff on their own.

S: You're correct.

C: What?

S: You're correct. I agree.

C: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

S: There's a selected population of lucid dreamers.

C: It's so selective, and they already are probably profoundly different than non-lucid dreamers in the way that their brain works during REM.

S: Right, but they have to be lucid in order for the study to work.

B: Then maybe you could train to be a lucid dreamer. There are techniques that you could do to facilitate that.

C: Well, then right there, that tells me their brains are different. Because if you have to train for something, you're reducing change.

S: Is training lucid or even inducing lucid dreamers introducing an artifact? That's the question.

C: That's what I'm saying.

S: Can we generalize from the lucid dreaming brain to just the regular dreaming brain? We don't know.

C: Exactly.

B: I mean, they're still in REM sleep. I mean, I think there's still a lot to be learned by that state, even if it is somewhat specialized in terms of people who have a natural facility for it or people that train for it. I think there's still a lot to be learned.

S: Yeah, we just have to be clear that the lucid dreaming state is different than the regular dreaming state. It's two different states of mind, that's all. And we don't know what's closer. Is lucid dreaming to being awake closer than lucid dreaming to regular dreaming, non-lucid dreaming? We don't know that question. I don't think we could assume that lucid dreaming is more like non-lucid dreaming than it is than being awake. Maybe you're mostly awake when you're lucid dreaming.

B: Yeah, I mean, I'm all for this research, obviously.

S: It's a hybrid.

B: I think there's a lot that could come out of this. I mean, lucid dreaming is, first off, it's fun as hell. The most fun I've ever had dreaming is when I've done lucid dreaming. It's an amazing time. Secondly, you can do things in your dream that you can't do in real life. You could be like therapy. You could practice doing things in a dream that you might be too frightened to try when you're awake, and you could actually build confidence in a dream to do something that you maybe never would try when you were awake because you're just too afraid to do it.

S: We don't know if that would work. The virtual exposure therapy doesn't really work.

C: It works to some extent.

S: Yeah.

C: Yeah, it depends. I mean, it's a buildup to the real thing always.

S: Yeah, but I read that there was at least one study recently where they did the virtual exposure therapy, and it wasn't as good as real exposure therapy.

C: Well, I would guess it wouldn't be as good. My assumption would be it would require more trials, or you might have to go more extreme in the virtual world than you would in the real world.

S: Anyway, we're getting a little off the main course of this discussion, and we need to move on.

Phage Viruses and Antibiotics (47:21)

S: Bob, tell us about phage viruses and antibiotics.

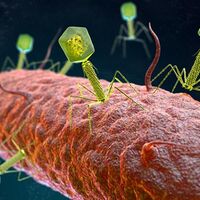

B: This was an interesting article I saw a little while ago. I haven't had a chance to talk about it. So researchers report in a study of a new surprising advance using viruses and antibiotics together to actually remove the antibiotic resistance of some superbugs, some bacteria, bacterial superbugs. So this was a fascinating partnership that was so cool. So this is published in Nature Microbiology earlier this year. Now, we all know about the fight against superbugs. We've talked about it on the show a bunch. Now, these superbugs are bacterial strains that we have stupidly evolved faster than necessary to become huge, huge problems now and potentially devastating problems in the near future. I mean, we're talking worst-case scenarios where humanity goes back to a pre-antibiotic era when no antibiotics work at all. I mean, this is something that's possible. And imagine you get a cut, a little cut, and you're like, oh crap, I hope this doesn't kill me. Imagine if that was a daily fear and something that needs to be taken seriously. So this takes me to Acinobacter baumanii, which is a bacteria. It's a superbug. This is one of the superbugs I'm talking about. It's responsible for up to 20% of the infections in intensive care units. I'm sure a lot of people in the IC dealing with COVID, not only are they dealing with COVID, but they're also probably dealing with the superbugs, a lot of them. And it's really insidious. The superbug attaches to medical equipment like ventilator tubes and catheters. If you have an infected wound, it's quite bad. Lungs, it can infect your blood. It's absolutely horrible. And they call it a superbug for a reason. It really is super. I mean, if the Marvel universe had superhero bacteria, this would be one of them. A. baumanii would be one of them. It actually produces enzymes that nullify whole families of antibiotics. Bam! None of you were getting near me just because of these enzymes. And then if the antibiotic actually survives the enzymes, it doesn't get past its sugar coating. And it actually is made out of sugars. This is a sticky, thick thing around the bacteria called a capsule. And some strains of this bacteria can shrug off the strongest and most toxic antibiotics. No matter what we throw at it, nothing makes any difference for some of the strains of A. baumanii. Now, the WHO says that it's a critical priority and we need new ways of treating this. And the CDC calls it an urgent threat. So we really got to start taking these seriously. So enter bacteriophages. Now, this is a virus. But not all viruses are like COVID. Some are our friends. Like this. The word bacteriophage itself means bacteria eater. And it's very apt. All they do is kill bacteria. That's all that these phages do. Just Google bacteriophage right now. Look at it. They look like aliens.

C: Yeah, they're badass living.

B: This is my favorite virus.

C: They look like Hydra kind of.

B: Right. So they look like an alien or some alien mech. I don't know. They're wonderful. So these were discovered over a century ago. But they lost favor when antibiotics came into power. We knew about them. I think we tried using it. I think the Soviet Union really used it a lot. And I think they may still use phages now. I mean, it's funny to think that if modern antibiotics were not discovered in that Petri dish, we may very well have a whole infrastructure of infection care based on bacteriophages right now. It would be really interesting to see how far that would have been taken in a century. But these phages are serious. I mean, real tough. The real toughest bacteria that laugh at people, they shit these little bacteria bricks when they see a phage because phages are very specific. Typically, one phage is meant for just one type of bacteria. It can get past only one type of bacteria's defences, or maybe it's the very close family of one type of bacteria. Now, of course, that reminded me of the classic Trek episode, that which survives. Steve, Jay, Evan, I'm sure you remember that, where an alien computer defends a planet by creating an image of a woman, Losira, I had to look that up to remember her name, to specifically kill one crew member. Remember, she'd say, I am for you, Jim Kirk.

E: You are the one.

B: And she couldn't kill anyone else, but if she touched Kirk, he was toast. So the researchers came up with a great plan. Their plan was really inspired. They found specific types of phages that could kill A. Balmanyi. And so they went to the areas like sewers, and really like sewers and other nasty places where some of these phages are. And so they got the virus, and they got the phages, and they threw them at Balmanyi, and most of them died, as you would expect, because they're really tailored to kill this specific bacteria. But not all of them died. Some of the bacteria adapted to the phage and survived.

C: Yeah, and that's really problematic.

B: Yeah, that's a huge problem. But in this case, it was a fantastic opportunity, because when the researchers looked at those bacteria that survived, they saw something amazing. There was no longer a capsule. That sticky outer coat was gone. So what the phage did was it realized that, I mean, the bacteria realized that, oh, damn, this phage needs this, really it needs the capsule to get inside, because that's how the phage gets past all the defences of the bacteria. It basically has a key into the capsule. And so the bacteria said, well, okay, I'll get rid of the capsule. And they no longer have the key. And that's exactly what happened. When it shed its sticky coating, the phage was helpless. It couldn't gain entry into the bacteria. But that's where our antibiotics come in, because now without that sticky outer coating of the capsule, now our antibiotics can get in, because that capsule was the thing that was preventing our antibiotics from getting in. That was actually the resistance, the armour that the bacteria developed over the years based on our antibiotics. So they would throw the phages at it. It would shed its capsule. And then the ones that survived had no capsule. Then they threw our antibiotics at it, and they tested like nine or 10 different antibiotics. And I got varying numbers here, but probably something like seven of the antibiotics now, the resistance was gone. So what they did was they essentially reverted the antibiotic resistance by using the phage and our most powerful antibiotics one after the other, like a double tap. And it really, really worked. And this worked in animal studies, and they actually did some real-world situations with people that had fatal infections, and it was successful. Now, I don't think this was a really huge study, but they did it on a handful of people, and it worked. To me, this is a great new angle for dealing with superbugs. You find the phages that are specifically tuned to that bacteria. You hit them with the phages, and then you hit them with the antibiotics once they've shed to the survivors so that they can get past the last defense that the phage couldn't. So it's a great way to temporarily reverse this resistance that we've been accelerating the evolution of. So pretty exciting. And I would like to see more phage use in the future, because one of the benefits the phages have over antibiotics is that phages are so specific. Now, you've all heard of broad-spectrum antibiotics, right? Yeah, that's great. But because it's broad-spectrum, you're killing a lot of the good bacteria. And you know, if you listen to the show, most of the bacteria around are really good. In fact, a lot of it in the human body is critical. You don't want to be messing with that. So something that can be specifically targeting that really bad bacteria and sparing the good stuff is great in my book.

Goop the Pandemic (55:44)

S: All right, Evan, I understand that Gwyneth Paltrow has finally found a way to exploit the pandemic.

E: Oh, yes, the queen of quackery, the duchess of dubiousness, the matriarch of malarkey. According to a recent blog post in which she is being pilloried for, correctly so, Gwyneth Paltrow claims she had COVID-19 very early on, apparently. She's not specific with things like exactly when she had it, which is a little unusual when I speak to people who have had COVID. They can tell me with precision when they tested positive for it. But that aside, let's take her to a word. Well, here are some words from her directly from her advertisement. I mean, her blog post the other day. These are her words. I had COVID-19 early on, and it left me with some long-tail fatigue and brain fog. In January, I had some tests done that showed really high levels of inflammation in my body. So I turned to one of the smartest experts I know in this space, the functional medicine practitioner, Dr. Will Cole. After he saw all my labs, he explained that this was a case where the road to healing was going to be longer than usual. We, meaning she and the doctor, have a version of a protocol he outlines in his forthcoming book, Intuitive Fasting. It's keto and plant-based. Will also got me on supplements, most of them in the service of a healthier gut. There's butyrate, which Will says supports healthy microbiome. And then in my daily Madam Ovary supplement, I get fish oil, B vitamins, some vitamin D3, selenium, and zinc, all of which Will says are critical for me right now. I even get more zinc and selenium along with the antioxidants, vitamin C and resveratrol in my detoxifying super powder, which I mix with water. All right, those are the highlights of the blog post. This is a shameless promotion basically, telling her readers to buy all sorts of goop-related and sponsored products, everything from, well, including hiking accessories and an infrared sauna blanket. Did we talk about infrared saunas recently?

C: Oh, yeah, we did.

E: Well, it didn't take long for those skeptical of Gwyneth to raise some keen observations about some of her comments. For example, there's Bruce Lee at Forbes. Yes, Jay, his name is Bruce Lee.

J: Now I don't believe anything you're saying.

E: No, that's his name, Bruce Wyatt Lee.

C: That's probably a good thing. Don't believe anything she's saying, Jay.

E: Here are some of his points. She didn't specify which tests she took, where the inflammation was occurring or what really high levels of inflammation even mean. Inflammatory, inflammation is a very vague and general term. So did she go to a medical doctor who has actual knowledge of COVID-19? Is Cole a COVID-19 expert? Has he done any research or published any scientific studies on COVID-19? Well, he searched the PubMed for Cole and COVID-19 and nothing really came up. So Cole was originally trained as a chiropractor, and on his website he asks himself the questions, are you a medical doctor? To that he responds, no. I do not practice medicine and do not diagnose or treat diseases or medical conditions. So isn't long COVID a medical condition, he asks? Yeah. So it's not clear what specific knowledge Cole has regarding COVID-19, but he says my services are not meant to substitute or replace those of a medical doctor. So there's your trapdoor disclaimer that you see with every good quack.

S: Also, functional medicine is bullshit, whether it's an MD or not.

E: Functional medicine.

J: Steve, give us a quick definition of that.

S: It's basically like massively overinterpreting lab results, like testing for shit and saying some really hand-waving explanation for what it means. But it's just another umbrella term for just non-science-based, made-up shit that I want to promote.

C: So these are the people who will tell you that you have too much metal in your gut and you need to chelate or too much fungus in your gut and then prescribe all of these drugs and then you have to chelate the drugs.

S: Or you have borderline thyroid dysfunction, or normal, either one, take your pick.

E: Oh, boy. I mean, there's so many relentless sort of attacks right now on Gwyneth, nd like I said, rightly so. Here's another small sample. I'll give you two more quick ones. Sarah Fielding from VeryWellMined.com. With much still being discovered about COVID-19 and its short- and long-term effects, a breeding ground exists for misinformation and exploitation. The latest example comes from Gwyneth Paltrow's lifestyle site, Goop. Oh, yeah. Paltrow uses her COVID-19 experience as an opportunity to promote unsubstantiated detoxes and cleanses while plugging Goop brand products under the guise of relieving discomfort. Oh, yeah. And he interviewed Tim Caulfield, Timothy Caulfield.

S: Yeah, he's great.

E: We've had on the show before. He's a professor of health, law, and science policy at the University of Alberta. And he's probably done more research on kind of the damage that Gwyneth and Goop have done to Western society, where Tim points out, it's a good example of how misinformation is going to continue to be pushed out in the context of COVID-19. We often think of misinformation as the hoaxes or the conspiracy theories and anti-vax rhetoric. But there's also this kind of misinformation, which is subtler, and still trying to leverage this moment in time, trying to leverage the pandemic in order to sell products to further a brand to even sell kind of an ideological position as to how we're supposed to be with our health. Absolutely correct. And a good observation by Tim.

S: All right. Thanks, Evan.

E: Yep.

Who's That Noisy? (1:01:39)

- Answer to last week’s Noisy: Ice Skating

S: Jay, it's Who's That Noisy time.

J: All right, guys. Last week, I played this noisy.

[_short_vague_description_of_Noisy]

All right, guys, any guesses on those sounds that you just heard? Go ahead.

E: All right. So to me, that sounds similar to the testing they did was back in the 70s or the 80s for sound effects in which they took metal screwdrivers and hit them against high tension lines.

J: Yep.

E: That was Bill Burr making sound effects for Star Wars, the very first film. You are not incorrect in that it sounds exactly like that.

E: OK, good.

J: But that's not it.

B: I got a hint of a classic Star Trek episode, Cat's Paw. You know, it was like the Halloween episode. And the creatures at the end when their true form was revealed, they made these really surreal noises. I got a little bit ahead of that. A little bit ahead of that.

J: Oh, my God. As soon as you said Star Trek, Bob, my brain heard what you heard. Yes, I know exactly what you're talking about.

B: Yes, right?

J: Now I have to go back and hear them. Now, it's not that, but I know exactly what you're talking about. But I know exactly.

S: Is it Ice Jay?

J: Oh, my God. Let's go through what the people say here, Steve.

S: All right.

J: Let's go through. So Jill Crookshanks. Does that remind you of the bad guy in...

S: That's the name of Hermione's cat.

E: Yeah, that's Hermione's cat in Harry Potter.

J: But what was the name of the king from...

C: Braveheart.

S: Braveheart.

J: What was the name of the king in that movie?

E: Oh, King Edward Longshanks.

J: Longshanks. Oh, God, I love that.

C: Longshanks.

J: Oh, you guys have done such a good job in that role. Okay, anyway. This is from a listener named Jill Crookshanks, and she said, "It sounds like someone playing Galaga in an arcade. You can hear the joystick and clearly the blasters. Thanks." I'm like I kind of think she picked up something here that might be there. So I said, yeah, I kind of hear that, but I want to hear what it sounds like. So I went and I listened to Galaga, and I downloaded some sound effects from there that were as close to what she was saying here. So listen to this. [plays Noisy]

E: Oh, my gosh, that brings back memories.

J: Right, Evan? All right, so it wasn't Galaga, but thank you so much, because just hearing those sounds always just makes me smile, and I can warp myself back to when I was in there playing that game. So we got another guest from a listener named David Barlow, and he said, "Hi, everyone, my guess is some sort of high tension cable snapping. Keep up the great work." So, yeah, Evan, you mean you're not alone. A lot of people guessed some type of cable, high tension cable. There were lots of guesses about the telescope crashing, which is not this is not anything to do with the cable. But my God, does it sound like cables rattling against each other? Again I've said this many times. That's why I love Who's That Noisy, because bacon sounds like rain, frying bacon and everything sounds like something else, which I find remarkable. Now, here is the winning guess. This was from a listener named Logan Callan. He says, "Hi, Jay, the noise from this week's Who's That Noisy is someone ice skating on a frozen body of water. It looks beautiful, but you wouldn't catch me on that ice." Now listen again. [plays Noisy] Now, to be fair, lots of SGU listeners guessed correctly or mostly correctly on this one. Ice makes this noise. If you throw a rock onto a frozen lake under the right circumstances, it'll make that high pew-pew sounds, you know. But in this particular circumstance, we have an ice skater that's skating on a lake where the ice is under pressure. So think about the ice kind of like pushing out against the land, and it's like pushing back in on itself. So first, let me tell you about the person that created this. The person wrote, I made this sound recording of a frozen lake in the winter of 2005 or 2006 in the area around Berlin. Frozen lakes are known to give off most of the noise during major fluctuations in temperature. The ice expands or contracts, and the resulting tension in the ice causes cracks to appear. Due to the changes in temperature, the hours of morning and evening are usually the best times to hear these sounds. And then he goes on to talk about the acoustic phenomena. It has an elastic type of sound. But another listener wrote in and gave a description of this. Glenn Ellert said the Who's That Noisy, episode 815 of The Ice Cracking. He said possibly due to a person skating. He was correct, but he was not the first. So he said the speed of a wave in a medium often depends on the frequency of the wave. This is known as dispersion. In the case of sound waves in ice, the higher frequency waves travel faster than the lower frequency waves. This is the explanation for the pew, the pew-pew sounds, which are the higher frequency sounds. And they arrive first, so you hear them first. And then the low frequency sounds is like the eww that follows. So it's pew-pew, right? So let's listen again.

B: Oh, cool.

J: So we have sounds being made, and the higher frequencies get to you first because they move faster in the medium than the lower frequencies. And it's a collection of sounds that makes that effect, right? It's a really good analogy to sound effects and Foley made in movies where they layer effects. So as an example, the Millennium Falcon engine sound of it starting up or having problems with the warp drive and all that stuff is six or seven different sounds layered over each other to create the whole effect, which I find fascinating because an expert sound engineer can create these soundscapes from different things that become something else. And I think it relates to this idea that all sounds, a human voice, is like chords being played. It's not one note. Our voices are made up of chords. Sounds are made up of collections of different kinds of sounds.

New Noisy (1:08:12)

J: Let's move on to this week's new noisy. All right, so there's a funny story here. So Charlie Ross has been a longtime contributor, supporter, patron of the show. We went out and gave a talk at Google. Many moons ago, Charlie set it up for us. We had a great time hanging out with him at Google. He gave us an awesome tour. And many times throughout the years, we've seen Charlie at conventions and everything. So Steve and I, this past weekend, we are doing our game show. We premiered our game show. It was a very soft release. We're still testing and still improving the show. We have a ton of things that we're going to be improving on it. But we're very happy to announce that Boomer versus Zoomer. Boomer v Zoomer dot com, if you're interested, is launched and Charlie is monitoring the chat, right? It's my job to monitor the chat while we're doing the show. And I see Charlie's name come up, so I read the chat real quick and he said, he says, I have a bag of meat in my refrigerator that's labeled Jay's balls. And I took a screenshot and I immediately texted it to Bob because I'm like, this is awesome. I know Bob would laugh at that and then I emailed Charlie and I'm laughing so Charlie has a great sense of humor and he's a great contributor and he also sent in a really provocative sound this week that I thought was vaguely similar to this week sound and that's I think why I was attracted to it because it is vaguely similar a little bit. But it is very different thing. So let me get to that real quick. So here is the sound that Charlie sent me:

[_short_vague_description_of_Noisy]

So what is that?

C: I don't like it.

J: What is going on? I know Cara I had the same instinct it made me uncomfortable.

C: I no like it. I feel like my dog would bark at that sound.

J: Yeah, so there is a single answer to this I know that you're hearing other stuff going on and you you could talk about that. But I'm of course I'm talking about the the high-pitched noises that you hear now. What what is this sound? What's generating it? What's making it? Where is it coming from? If you have an answer, please email me and if you have a cool sound that you heard you can also email me at WTN@theskepticsguide.org

S: All right coming up. We have a great interview with Philip Goff. He is the philosopher that we talked about recently on the show in our discussion of the inverse gambler's fallacy and inferring the multiverse from the fine-tuning problem. We have a very interesting discussion. This is actually only part of it. The full one hour unedited discussion that we have will be available to our premium members if you want to skip ahead because you want to listen to the full version then just go to the 1 hour 39 minute mark that will take you to the end of the interview, but for everybody else let's go to that interview now.

Interview with Philip Goff (1:11:16)

S: Joining us now is Philip Goff. Philip, welcome to the Skeptics Guide.

PG: Brilliant. Thanks for having me. Good to be here, Steve.

S: Yeah, thanks for joining me. So Philip you are a philosopher you are the author of the book Galileo's Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness which we were just talking about is probably I'm going to have to interview you at a separate time about the whole consciousness hubbub. But the interview today is a follow-up to a discussion that we had on the SGU recently about the multiverse and the alleged fine-tuning problem and some of the logical claims surrounding that. I talked a bit on the show about an article you had written. And I disagreed with your ultimate conclusion. Now I think the goal of this conversation is to see if we could work out our differences. Basically, I want you to convince me that I'm wrong. Not just show that I'm wrong, but convince me that I'm wrong because that's that's the tricky part. So why don't you just set the stage for us? Tell us about the fine-tuning issue and how you came to write this article.

PG: Yeah, okay. Well, I'll do my best. That's it. That's a big big order to persuade you, but I'll do my best. So that the fine-tuning is the surprising discovery of of the last few decades that certain of the constants of basic physics such as the strength of gravity and that the mass of electrons, in order for life to be physically possible, the values of those constants had to fall in a certain really narrow range. And that was quite surprising in some way. Of course We always knew that our universe was compatible with the existence of life because we're alive. But we didn't know how balanced on a knife edge That was that in order for that to be a physical possibility these constants had to be as it's as it's referred to finely tuned. They had to have these very precise values. So it's a kind of interesting surprising fact. Some people react and say, okay, we got lucky, not not more to say about it. But many scientists and philosophers the last few decades have suggested that this is actually strong evidence pointing to some kind of multiverse. So that the thought is if there are a huge number of universes each with the constants in their physics a little bit different. So, you know in some gravity is a bit stronger and some it's a bit weaker and some electrons are a bit heavier and some they're a bit lighter then if there's enough variation then you then it might become sort of statistically highly likely even perhaps inevitable that one of the universes is gonna fluke the right numbers to allow for the compatibility with intelligent life. So that's the thought. And I was actually really persuaded by that but for a long time actually, but I uncovered this work of of certain probability theorists. Philosophers of probability. It's actually a few decades old now and I think it's part of the problem of things are so specialized now that there's been this debate for decades and it hasn't got out of the narrow confines of theory of probability theory. Even though there's such huge interest in these fine-tuning issues among scientists and the general public. But anyway, the claim is that that inference from the fine-tuning to the multiverse commits a kind of logical fallacy. We can actually identify what the fallacy is and I thought about this for a long time read read the literature around it. And yeah, I mean, I'm actually quite persuaded that the claim is correct here.

S: Yeah. So my understanding of it is and correct me from wrong is that whether or not there are many universes doesn't alter the probability of our universe being fine-tuned for life.