SGU Episode 927

| This episode needs: proofreading, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 927 |

|---|

| April 15th 2023 |

Amprius Technologies claims an energy density of 500Wh/kg and 1.3kWh/L from its latest lithium-ion battery technology. This is about double the capacity of today's general purpose cells.[1] |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

JB: Jon Bornstein, |

| Quote of the Week |

A large portion of overconfidence stems from a desire to feel certain. Certainty is simple. Certainty is comfortable. Certainty makes us feel smart and competent. Your strength as a scout is in your ability to resist that temptation. |

Julia Galef, American philosopher |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction, Florida flooding

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Thursday, April 13th, 2023, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening everyone!

S: Jay is off this week. He's out gallivanting with his family or something.

C: How dare he.

S: I know.

E: How dare he miss a week. Oops. It's good to be back everyone.

S: I haven't missed a week in 18 years.

C: Wow.

E: Is that right?

S: That's right.

C: I have.

E: We all have.

C: Yeah.

E: Except Steve.

S: But in fairness, that's because we work around my schedule.

C: Oh you're right.

E: It makes sense.

C: That's true. Yeah.

[talking over each other]

E: You know how to push the buttons and turn the thing on.

S: I know. I have to make it happen.

B: I just sit here and look pretty.

C: So I almost missed tonight.

S: I know. We were scrambling.

C: You guys, it's biblical out there. And I don't think I realized it. Since Monday it's been raining nonstop in South Florida. And yesterday, so Monday was pretty like whatever. Okay, it's raining. It always rains. Tuesday I work from home so I didn't really realize it. Wednesday I go in and I was like hmm, there's a lot of flooding out there. And then it was like, two tornado warnings while we were at work. People canceling, not showing up to the clinic. I walked home and the flooding was up to my knees.

B: What?

C: Yeah. And then I just saw online, I just shared it actually on Instagram and you can see some like great flooding videos that I posted on my Instagram. Florida's previous rainfall record for the entire month of April, 1979, they got 19 inches in the whole month of April. Yesterday we got 25 inches in seven hours.

B: What?

S: Yep.

E: Nothing compares. Nothing compares to that.

C: What? And it's still raining outside you guys. So I lost power earlier which is why I almost wasn't able to come. But the power was restored. My internet's back up. I am here.

S: Let's hope it holds.

C: Yeah. Well it actually, the rain right now is just a steady flow. Earlier it looked like, I took video from inside my patio sliding doors and it looked like I was in one of those drive-thru car washes. Like that's, yeah, it was that bad.

E: Sheets of rain, sheets of water pouring down.

C: Bananas. Crocs came in handy. Had to put them in sport mode.

E: I wonder if this was one of those atmospheric rivers that I've heard about, read about. And I know they happen in California, I just never heard of them happening in Florida. I don't know if Florida's really situated for them.

C: I think it's just rain. Like it's like hurricane levels of rainfall without a hurricane. Or at least that's everything I've been reading.

E: How windy has it been?

C: Today was very windy. Yesterday the wind picked up a little bit. It wasn't so bad earlier in the week. But today it was raining sideways, fo sho.

S: And is all the flooding due to the rain itself or is there any surging of the ocean waters?

C: As far inland as I am, there's no way that this could be ocean water. I'm in Davie.

B: It's not a low pressure because if it were, then by definition, wouldn't that be a hurricane or tropical storm?

C: Yeah, I don't think it is. It doesn't have any of the kind of classic features.

E: I think the steadiness of the wind defines whether it's a tropical storm or hurricane.

C: But aren't they also like a cyclone-y shape?

E: Yes.

C: Yeah. And I don't think it looks – the Doppler didn't look anything like that.

E: Yeah, it has to have a form, a structure.

C: I bet you in Fort Lauderdale proper, like by the water, a lot of the flooding is storm surge stuff coming in from the ocean. But where I am in Davie, I am so far inland. It's just there's no drainage here or I don't know. The city planning is not great. There's no sewers. There's just nowhere for the water to go. So there's a lot. Don't get me wrong. Where I live, luckily, it's not all concrete. I'm very close to the Everglades and there's a lot of greenery. There's a lot of grass. There's a lot of soil. But it can only be – once it's fully saturated, it's fully saturated. And all of the storm, like all the dips and rivers and little pond-like areas, they're just flooding and overflowing into parking lots.

E: And what happens also is the wildlife goes – spreads out. Alligators everywhere, snakes in places.

C: Yeah. Oh, yeah. Actually, a friend of mine posted just in her neighborhood, she was filming. It was so bananas looking. It was like – I think it was her lawn. It must have backed up to a lake or something and there's lakes everywhere. But her lawn because you could see the grass under the water and there were fish swimming like at her feet.

E: Sure.

C: I was like, what is happening?

E: Oh, my gosh.

S: And can they have – how effective are the storm drains? I know you can't have a basement in a lot of locations in Florida because the water table is so high. So there's no place down like for the water to go.

E: Nope.

C: There's – in my apartment building, there are storm drains and you know they're storm drains because they say no dumping, empties to the ocean or whatever. And I don't – and where those drains are, there is not standing water. So at least maybe something about the architecture of my apartment building that works. But when you're walking down the street – I grew up in Texas and every curb had those linear drainage things at the ends of them. We don't have that here. So the street just floods up and over and you can't see the curbs anymore.

S: Right. I know they have storm water management but it's supposed to be particularly challenging.

Steve's stress echocardiogram (5:37)

S: So have any of you guys ever had a stress echo?

E: Stress echo.

C: Yeah, like an echocardiogram?

S: Yeah, but a stress echocardiogram.

C: Yeah, where you're on a treadmill?

S: Yeah.

C: Yeah.

S: You did?

C: Did you have one recently?

S: I had one yesterday.

C: How did it go?

S: Good. Yeah. So I had a stress test before. This is the first time I had a stress echo. So they do a baseline echo so looking at your heart with the ultrasound and they look at the size, ejection fraction, contractility, wall motion, all that stuff. Then you get on the treadmill for like a regular stress test. So I had to get my heart rate up to 137. That was the target heart rate, which was tricky because I'm on a Tenolol, which is a beta blocker, which blunts my heart rate response, right? So I had to work extra hard to get my heart rate up to, I just barely made it. I barely got up to 137 before the test was over.

B: Really?

S: Yeah, it was hard, you know.

B: Tenolol does that?

S: Yeah, it's a beta blocker. It can actually, in some people, Tenolol actually is a partial agonist, so it's not as bad as some of the pure blockers, like propranolol, for example. It can actually cause exercise intolerance because it blunts your exercise response.

C: Oh, interesting. That sounds sad.

S: That's why some people get fatigued on it. They can get exercise intolerance, which I don't have any of that with the Tenolol, but it still does blunt my heart rate response. So anyway, so I had to work really, really hard to get my heart rate up and everything. And then as soon as you're done, like you have to like jump onto the stretcher, roll over, and they immediately do another echo while your heart is beating at maximum strength.

C: Yeah, get it.

B: To track your recovery?

S: Well, they want to see the difference between your like resting heart function and your exercise heart function.

C: Right, because they're like looking at and during an echo, they're looking at a lot of stuff. They're looking at the actual muscle.

S: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So they look at, they're looking for a couple of things. When you're exercising, the heart should be beating stronger, right? So your ejection fraction, the percentage of blood that you're squeezing out of your heart should go up. The heart should get smaller when it contracts because it's contracting more.

B: Yeah.

S: It should get, I think it also gets bigger, right? So it gets bigger and smaller. Like it's going through a greater range of volume changes in order to pump more blood. And they look at how all of the heart muscle walls move to make sure that they're all moving well. Because if you have any like regional wall motion abnormality, that could indicate that either you've had some damage or it's not getting that part of the heart's not getting good blood flow.

C: Right.

S: Of course, they also, during any stress test, they also look at your EKG to make sure that there's no signs of ischemia on your EKG, on just the electrical activity of your heart. So anyway, mine was perfect. So it was good.

E: Oh, good.

B: Good to hear.

E: That's important.

B: You could have led with that.

C: What reason did you have to do it?

S: Because first I'm 58. That's part of the reason why. I have hypertension. I get palpitations occasionally. And I have a little bit of blood pressure, liability. It's labile blood pressure. So they just did it to be on the safe side.

C: Interesting.

S: The hardest part though, so when they're doing the echo, you have to take a deep breath and hold it. Right?

B: When you're recovering from the exercise, the cardio?

S: Exactly. So it was not a problem at baseline, at rest.

E: Sure.

C: Right.

S: But imagine doing like your most intense workout and when you're like breathing as heavy as you can, now hold your breath. Like you basically can't do it, you know?

B: Yeah.

S: Because you're screaming to blow off that CO2. Like your brain is like really maximal respiratory drive.

E: Yeah.

S: So I was only able to do it for like a second at a time. But they were able to get the images that they needed. But that was the hardest part. I'm like huffing and puffing. Now hold your breath.

E: You hold your breath.

C: I had to get some really intense workups previously. And it turns out that I have something called inappropriate sinus tachycardia. But she doesn't even like that diagnosis because apparently people who usually have that, which is basically just like a fast heart rate, have palpitations too. And so like when I was wearing a holter monitor for a whole week, you're supposed to keep a log of every time you have palpitations and push the button. I never had, I've never had a palpitation. I don't know what that feels like. It just feels like your heart is going too fast.

S: Well, it could be a number of things. It could feel like your heart pauses or skips a beat. It could feel like a-

C: Like a flutter almost?

S: -it could feel like your heart beats, like has an extra beat thrown in there or it beats like inappropriately strong one time.

C: Interesting. Yeah, all of that.

S: I've had all those variations on palpitations.

C: That does sound scary. I think I told you guys all of that happened because I was wearing a fitness monitor and it kept going off and being like abnormal heart rate, abnormal heart rate.

E: Oh, this is a problem with those things.

C: And then resting pulse really high. Yeah.

E: Yeah, it's a problem with the wearables.

C: And that's basically, I mean, it's good that I got it checked out, but basically the outcome was, your heart beats fast. Nobody knows why. The heart muscle is super healthy, even when it's stressed. Don't worry about it. Come back in 30 years.

S: But that is a good point though. And I remember learning this even in medical school that when you start to increase your surveillance of whatever biological parameters of patients, they can have unintended consequences. Like, for example, I remember when I was rotating through OB delivering babies and it was in vogue at the time to do the intrauterine monitor. Like you would stick a lead literally on the baby's head to record their heart rate, right? And it led to an increase in C-sections because the heart rate because like when you do a contraction, the baby's heart can stop or it could temporarily or it could drop their pressure and you could do all kinds of things. So basically everyone was freaking out at the normal stuff that was happening during delivery and then they were panicking and leading to C-sections. So then the discussion became, maybe we should just not do it routinely. We'll do it on high risk births or if we have a reason to do it. But just like if we don't, if we just don't look, we won't freak out at this normal stuff that's happening that looks scary. So this is the same kind of thing where it's like, yeah, if you, if like you lived your life with a heart monitor, there's probably all kinds of weird rhythms that your heart goes into every now and then that you may mildly feel it or not feel it at all. And if you just ignore it or don't know that it's there, you go about your life and it's nobody and there's no problem. But if everyone knows about every little thing that's happening, how many follow up tests is that going to result in? How many false positives will that result in? How many unnecessary procedures or prescriptions of medications or just anxiety? People think they're going to die.

C: Oh, anxiety. I utilize this principle all the time in psychotherapy. This concept that yes, there is "normal", like they're normal, they're norms tables. And there we can look at population data. Obviously we know that there are norms tables. There's normed data that comes from population level statistics. But when you look at fitness monitors or even like you were talking about kind of medical norms, those are population level. We're not comparing ourselves to ourselves. That's how we should be looking at our bodies. What is our baseline? How do we look under stress? How do we look under whatever? Like that kind of personalized medicine future we're always hoping for and thinking about. But when if we're to monitor every single if we're to take our blood pressure 10 times a day every day, sometimes you're going to be like, that's weird. But it's normal to be abnormal sometimes.

E: That's the point. Yep.

C: That's the point. Yeah. It's normal to be abnormal.

S: Or just that the range of normal is greater than we think. That's another principle you learn in medical school. Before you know what's abnormal, you need to learn the full range of what's normal. Which is greater than you think, right? Because people don't read the textbooks. They don't necessarily follow the pristine what is "normal" in the textbook is like 60, 70, 80% of like most people. But there's 20, 30% of people who are just different. And it's part of the normal range. And we don't get too excited about it. But you got to learn what that range is.

E: Right. Yeah.

C: Yeah. And it's contextualized. I think that's the other thing. I always I love talking about the principle of like you are having a normal response to an abnormal situation as opposed to this is an abnormal response to a normal situation. Because I think so often, definitely in psychology, but I can imagine Steve that in medicine you see this too, where like the parameters that we're used to working with are contextualized like at rest or under like normal conditions. And it's like, yeah, but what about, like you said, in a stress test? That's why we have to do that. What's normal heart functioning after you've just exercised? It's different than at rest.

S: Different. You don't do stress tests as a mental health. I guess life is a stress test.

C: No. Life is a stress test. So, so often, I mean, I see this a lot in end of life work and cancer and stuff when people are like, I'm crying. I've just been crying all day, every day. And I'm like, you were just diagnosed with cancer.

S: That's normal.

C: It's normal to cry all day, you know. But a lot of people, it's, we don't know because there's that pressure to somebody so much as like sheds a tear and it's like, oh, I have depression or oh, you know. So those kinds of conversations I think we should have. What is that normal range? It's important conversations to have.

S: Absolutely.

News Items

Dopamine Detox (15:14)

S: So guys, let me ask you, have you ever heard of dopamine detox?

E: I've heard of each of those words separately.

C: Is that like a tech detox?

S: Dopamine, yeah, kind of.

C: Like a cell phone detox? Yeah, I mean.

S: Sort of.

C: I sometimes recommend that to some clients, but not like, I don't call it that.

S: But this is more than that. It's more than just a tech detox. It's dopamine detox. Cara, you're going to hate this.

C: Yeah, you can't detox yourself from dopamine. It doesn't make any sense. It's endogenous.

E: It's kind of important. You wouldn't, why would you want to?

C: Also, yeah. So why would you want to? That sounds horrible.

B: It sounds like something Vulcans would do.

S: So yeah, I mean, this is a new trend. I think it's very popular in Silicon Valley now. And I hate everything about it because it's like, it's totally built on self-help pop nonsense that misunderstands how the brain works and how addiction works and how dopamine works and how detox works all kind of rolled into one.

E: To get it all wrong on every level.

S: Other than that, it's great.

C: Nutraceuticals!

S: So all right, so what's going on? So the claim is that people are overwhelmed with dopamine because we're constantly doing things to give ourselves a dopamine hit, right? And so you spend either like a couple, a certain amount of time per day or certain amount of days per week, like one day a week or a week a year or whatever, where you avoid anything that would give you dopamine in order to sort of reset your brain so it's not addicted to dopamine, right?

E: Okay, that sounds impossible.

S: Yeah, it's dumb. But let's go a little deeper and say exactly why. So first of all, it misunderstands the nature of how the brain works and how neurotransmitters work and what dopamine is, right? So dopamine is a neurotransmitter. It has, there are many subtypes of it and it has many effects in the brain. It is the neurotransmitter that is involved in some of the "reward circuitry", the circuitry that makes us seek out behaviors or engage in behaviors that are reinforced by the reward circuitry, right? So I think some people misinterpret that as like it's the pleasure neurotransmitter, like dopamine gives you pleasurable sensation. And that's not really what it is. It's that pleasurable sensations give you, depending on what they are, reinforce your reward circuitry, which is where the dopamine comes in, right? The dopamine itself doesn't feel good. It's like you do something that feels good.

C: You can't even feel dopamine. Like cocaine feels good.

S: Yeah, it's not like a drug. It's not like a drug that activates your brain. It is just part of how the brain functions.

C: But the interesting thing is when you take cocaine, it acts on your dopamine system. You know what I mean? So it's like-

S: But if you took dopamine, it wouldn't make you feel pleasurable or wouldn't necessarily reinforce any behavior.

C: Right, ask people with Parkinson's disease.

S: Yeah, we give people dopamine for things like Parkinson's disease because dopamine is used in other parts of the brain, like the basal ganglia, which is involved in movement, or in some of the frontal lobe projections that are involved with thought, some higher order thought. So for example, the reason why you actually don't give dopamine, you give pre-dopamine, right? The precursor of dopamine.

C: Or the L-Dopa.

S: The L-Dopa. And the reason we do that is because the dopamine producing neurons in the basal ganglia are dying off. And so dopamine is the rate limiting step now for that function. And you can give a little boost to the function of that part of the brain by giving more precursor, right? So that you're basically forcing the cells that are still there to overproduce the dopamine to try to make up for the fact that there are fewer of those dopamine producing neurons in that circuit. But here's the thing, it also causes side effects. And those side effects are because dopamine is also a neurotransmitter in other parts of the brain.

C: Right, it's involved in memory too. Like I would not want to not have dopamine. This seems like a bad idea.

E: Well, that's the point.

S: Yeah, it's not even, it's just it's flawed on every level in terms of how they think dopamine works. And so the idea of detoxing from a neurotransmitter is nonsensical. But you might say, okay, that's just the buzzword, the wellness buzzword, detox. But is there anything to avoiding activities which are addictive in order to sort of reset that reward circuitry? So let's look at that for a moment. So first of all, I think that is based upon a misconception as well, because it treats behavioral addiction as if it were chemical addiction. And they're not the same thing.

C: No, they're not.

S: Yeah, you need to detox from a chemical addiction because the chemical itself is reinforcing your reward circuitry. And it's the responsiveness of your receptors to that chemical is what is being downgraded and what you need to reset. The same isn't true of the neurotransmitters that happen to be involved in the circuitry of the reward. It's not the same thing.

C: Well, and also, like, it's just so complicated. But like, honestly, if you have a behavioral addiction, you need to make behavioral changes and cognitive changes, by the way. But to be clear, even if you have a drug addiction, yes, you do need to detox, but you also need to make behavioral changes.

S: Totally, because it's both. Yeah, chemical addictions are both. They're chemical and behavioral. But you can have behavioral addictions that are just behavioral.

C: Right, exactly.

S: Yeah, and that doesn't mean that there can't be medications that which might help you. Like you might use antidepressants or whatever that might be helpful and combined with cognitive behavioral therapy or whatever in order to change your behavior. But at their core, they are behavioral. That's kind of the whole point. And they still involve, like, you making choices about how you're living your life. It's not the same thing as a chemical addiction where you have no control. And so the other layer here that I really dislike is the idea of blaming the brain for your behavior. It's like, my brain's doing this. I'm not doing this. Like, trying to make this magical separation between the two.

C: I push back against that, not like for kind of like normal use. But I do think that can be an effective strategy for people who have severe mental illness is externalizing the experience. So externalizing the depression, externalizing the anxiety can be really helpful.

S: I agree with you. And as I was about to say, is that it goes both ways. Because there are people who blame the person when it really is a brain problem and people who bring the blame and it really is a behavior problem, like a choice problem. And you can't just assume that it's one or the other. But I think people decide which one it is because that's what they want it to be rather than because that's what makes sense or that's practical. And so yeah, so if you have a major depression, for example, yeah, that's there's something going on with your brain chemistry. That's fair. If you have ADD, like this is famously ADD was blamed on bad parenting. It's not bad parenting. It's your brain hardwiring, right? But this is sort of the other problem, saying, I'm a sex addict. It's not my fault. It's something to do with your brain rather than the life choices that you're making.

C: There may be some in between with it. We don't know yet.

S: It's complicated because the brain is an organ of behavior and does interact with the environment. So it's not cleanly separated. But you know what I'm saying, Cara.

C: Yeah, I know what you're saying.

S: Yeah, it's not just like a way of giving you more power over your issues. It's a way of absolving you of responsibility for your issues.

C: And even beyond that, it doesn't, like, here's my thing. It doesn't work. Like if you tell somebody who wants to lose weight, just stop eating for a few weeks and then you can just start eating again. Well, I know that that's not realistic, but this is yo-yo dieting, right? People will go, okay, I'm just going to make this drastic change and then I'm going to go right back to how I was the minute I'm done, which is what a dopamine detox, I'm assuming is what they're talking about.

S: Instead of like, let me find out what my actual issues are and make some lifestyle changes that may be long-term work. Let's do this one crazy trick life hack thing. I'm going to do a dopamine detox, then I'm good, right? Then I can go back to all the work I was doing.

C: And then all of a sudden, like, I'm going to throw my phone, I'm going to lock my phone in a box for a week and then I'm going to unlock it and I'm going to have a better relationship with my phone. Like, no, you're going to go right back to the addictive behaviors that you've already had. You have to learn healthier behaviors with your phone.

S: Exactly.

B: So is externalizing wrong then? Because I recently got into the habit of like when I do something stupid, like recently I left my coffee on the trunk of my car and I'm about to drive away and I'm like, oh, Bob, you almost got me. Sorry. You punk. I got you this time. Trixie. Bob is Trixie. No. Is that good? Is that bad?

S: It's complicated.

C: It can be good. It can be really bad. Like, you don't want to – this is actually a funny argument within psychology circles is the idea of dissociation and trauma and its relationship. And there are some treatments like internal family systems theory, which does not have a lot of good evidentiary support, that is all about saying the part of me that does this, the whatever part of Bob left his coffee cup on the car, which can be really helpful for some people. But for people who tend towards dissociation, that's probably wildly dangerous. So it's complicated. It depends on who you are.

S: It's complicated. There's a lot of nuance there.

B: I'm going to keep doing it because it's funny.

C: Here's the thing. Does it help you?

B: It makes me laugh.

C: There you go.

E: That's good.

B: Whoever's I'm with, it makes Liz laugh. So I'm going to keep doing it.

C: And does it keep you from being too hard on yourself?

B: Yeah. I'm just being goofy.

C: Yeah. Then it's good.

S: So yeah. Cara, the thing is, as we both know, it's very nuanced. And I am all for understanding – I mean I talk often on the show, understanding our neurological selves, right, in order to first of all, not beat ourselves up for being human and also not try to be unrealistic about your goals or try to like brute force your way to what you want, your behavioral changes or whatever. Because it's good to recognize, yeah, I have frontal lobes and I have my basic desires and this is how they interact. I find that all very helpful and it's true and it could lead to actual some practical things. But this sort of simplistic notion of, oh, this is not me, it's my brain regardless of what the reality is, is counterproductive.

C: Well, and to me, this whole digital detox – whatever, I keep calling it digital, but dopamine detox thing is a brute force attempt at hacking. It's ridiculous.

S: Right.

C: It's not developing healthy coping skills.

S: Anything to avoid long-term actual work, you know?

C: Right. Exactly.

S: Like let's just do this. Again, it's the hack. I want this one quick hack rather than actual work, which is like the entire self-help industry, you know what I mean?

C: Which is why so often, I can't tell you how often people will come into the clinic and they'll sit down and we'll come up with our – you know, we'll do the full intake and then we'll do our treatment plan and we'll come up with our goals. And four sessions later, I'll get a call from the parents like, is my kid fixed yet?

E: Yeah, right.

C: Oh, no. That's not how this works. Also your kid's not broken. There's a lot to talk about here. But it is. It's a problem. We want the quick fix.

S: Exactly.

C: And that's tough, man.

S: Right. Dopamine detox.

C: It's not going to work.

S: Pushed all my buttons. All right.

C: I can imagine.

Overprotection May Cause Anxiety (27:26)

S: All right, Cara, tell us about the effect of overprotective parents.

C: So a psychologist wrote this article. They cite a lot of evidence to try and formulate an argument, but the argument itself still, I think, does require some – not so much logical leaps. I think that he does make a relatively solid argument, but it's not like a study will ever tell you this. So bear that in mind, right? This is not the result of a single study. But basically the argument that this psychologist is making is that modern young people, like children today – and really they start looking at the evidence from around the 70s, 80s, 90s, and beyond – are dealing with mental health issues in very, very large numbers, as we know. If you compare pre and post demographic information between those kind of decades, we definitely see that suicidality, depression, anxiety, loneliness, all of these things are more prevalent. Now, I do think it's important that we caveat the hell out of that. I think that we're better at taking this data down now. I think we're asking the right questions now when we used to not. I think people are more forthcoming with their mental state because there's less stigma around mental illness. And I also think that the world is more difficult. Like there are literally political and climate change – like there are existential concerns that teenagers and young adults are facing now that they weren't before. So we've got to remember that this all happens with a lot of variables. But basically the author of this article is making the argument that safety and an overemphasis on safety is actually doing more harm than good. I think he goes a little too far to be like, this is what's responsible for the rise in anxiety and depression among teens. I don't know if I would make that argument, but it might be a variable that does contribute. So basically this idea that good intentions of parents today who understand adverse childhood experiences, who understand that corporal punishment is detrimental to the mental health of their children, who understand things that just our parents and our parents' parents and our parents' parents didn't understand sometimes are swinging the pendulum so far and sometimes that are so anxious and afraid themselves of the boogeyman. I mean I can't think of a better way to put it, right? The news cycle is what it is. It's very different now than it was. Actually cable news wasn't even really all that prevalent until – when was that? Like the mid-90s?

S: Oh, I think late 80s, 80s.

C: Late 80s? Okay, late 80s, early 90s is when most people were starting to watch cable news as opposed to just the nightly news like on the main channels, which was a completely different thing. And so – and it is actually interesting when you look at the sociological data and the crime statistics that even as crime rates went down kind of around that era, that fear and anxiety went up and coverage of crime went up significantly. And you saw this – this is written from both an American and a Canadian perspective. Obviously we can't speak to other countries. But so the idea here, the argument here is that if we obsess about safety with children, and I think we do see an outward effect of this. Like when I was growing up, and I hate to be that person when I was a kid, but we would go outside and play. And it was like come back when the street lights turn on. And my parents had no idea where we were. We didn't have cell phones. They couldn't get in touch with us. And we were not supervised. And I know that there's always a bias of things were better when I was a kid and we should do it the way we did when I was a kid. But the data actually do show that children don't do as much independent activity. Children are more often supervised by adults. And there's actually a delay in their utilization of more, I guess, mature/adult/independent life skills. So kids are driving later. Kids are leaving the home later. And kids are identifying themselves as being more afraid. And sadly, that does seem to have an impact on their resiliency. And so as much as I think that this is a complex, nuanced argument that's maybe made a little bit too simple by this one particular article, I do think it's an important conversation to have. Our parenting styles affect our children. Not just our parenting styles, our social pressures affect our children. And kids today are more anxious than kids ever were in the past.

S: Parenting styles definitely have shifted. I think the whole helicopter parenting is absolutely real. And there's a lot of studies out there for that, but also just anecdotally from my end, because my wife and I have both been in higher education for 30 years. And it's palpable. I mean, it's palpable. Parents of college students today do things that were unthinkable when I was going to college. Parents calling teachers about grades and tests.

C: Which is, by the way, illegal. It's not illegal for the parents to call the teachers, but it's illegal for the college professors to release any of that data.

S: Yeah, but I'm just saying, when I was at college, my parents had no idea what was going on. They got my grades once a semester, and that was it.

E: That's right. You saw a report card.

S: They had zero idea. They wouldn't even know who to call. The idea that they would in any way meddle with my relationship with my teachers or how I was doing, it's just unthinkable.

E: Only if there was a serious problem.

S: Yeah, sure.

E: They had a fight or something.

S: There was some kind of disaster or special needs or whatever. That's different. But I'm just talking about for a regular student doing whatever, doing their thing. It's just incredible. And just, again, my wife works in a counseling. Now she teaches, but when she was working in a college counseling office, parents would call them saying their roommate's being mean to them. Like, really? You're getting involved at that level with a 20-year-old?

C: And here's what happens. And we know this because there are actually studies that really, really interestingly and creatively tap into this. And I'm going to take this straight from the, it's a line straight from the article. "Parental overprotection has been shown to foster unhealthy coping mechanisms in children."

S: Exactly.

C: "Overprotected children tend towards depression, anxiety, and they also tend towards defiance, delinquency and substance abuse."

S: Yeah, because they don't have the skills or the emotional resilience for what-

E: Can't cope. They can't cope.

C: Emotional regulation can be taught by offering, like mirroring. It can be taught by showing the, like if parents have good emotional regulation, yes, their children are going to learn by seeing, but they also, and so don't get me wrong, that's like a huge part of teaching a kid good emotional regulation is you need to be good at emotional regulation.

S: Absolutely.

C: And when I say emotional regulation, I don't mean hiding your emotions. I mean having healthy experiences with emotions, but they also have to learn by having their feelings. They have to experience things that are stressful in life, things that seem unsafe or feel unsafe, but actually aren't unsafe. And the problem is we are protecting children from even feeling that lack of safety. And so they don't know what to do when they are faced with actual unsafe things because they don't have any coping skills. And that's worrisome. It's really worrisome.

S: Yeah. I mean, it even penetrates into the education culture significantly, not just parents. So like for example, I don't remember if I brought this up on the show before, but like the standard educational approach now is to not do anything that stresses out students. Because there's evidence that shows that they perform better or whatever if you don't do anything that stresses them out. For example, you shouldn't even ask a student a question that has a right or wrong answer because they might suffer the stress of not knowing the answer or of being wrong.

C: But that's not inherently stressful.

S: But I'm just saying that this is where we're at. I'm telling you what I was taught to do. Or how about this? You can't praise a student for doing a good job because that will make other students feel jealous or like, well, why am I not getting praised?

C: Well and here's the real problem with this kind of thinking and this kind of rhetoric is it takes all agency away from good educators. We know it's true that you can't single particular children out and constantly praise them at the risk of the other students always feeling like they're not seen. That's not healthy.

S: There's something there. Absolutely.

C: But a good educator doesn't need a directive so that they're scared to go outside of this really, really constrained rule. A good educator has to use their best judgment. We need to teach them what happens psychologically when children are faced with these different experiences so that they can use good judgment in their teaching.

S: Not only that, I wonder about the difference between like an immediate effect versus a cumulative effect. Like sure, that student may be happier now but if over the course of their education they never had to confront the prospect of being wrong, that's just – it just seems to me that that's a problem, that that may have some negative consequences.

C: Of course it is. And I think the thing is like – so basically we can look at the literature and we can say, okay, children are going to – children often self-report negative experiences when their teachers do X, Y, and Z. And so then the educational system says teachers don't do X, Y, and Z. But that's very different than saying overcorrect in the other direction.

S: I think there's an overcorrection.

C: Yeah. I think that's usually the problem. For example, yes, we shouldn't stress kids out intentionally at school. Kids are stressed as it is. They are completely – like they are scheduled in a way that children were never scheduled previously and the homework load is higher than it's ever been. The pressure to get into college is higher than it's ever been. And yes, stressing out a kid for the sake of stressing them out, which has been an educational strategy in the past, but being like, I'm going to toughen you up, boy. That is not healthy.

S: I agree. The Severus Snape approach doesn't work either.

C: It doesn't work. But being so afraid that anything–

E: That's a Harry Potter reference, by the way.

C: Oh, thank you. Thank you. Being so afraid that anything will cause stress is also not appropriate. It's finding the balance.

S: It's a balance.

C: It's a nuance.

S: Right. We need to get back to a balance. Yeah, I agree. You should take a nurturing approach. It's good to ask sort of open-ended questions and like what do you think about this and get engaged rather than what we call pimping in medicine, which is just asking a bunch of factual questions like grilling.

C: Just to like embarrass somebody for not, yeah exactly.

S: Yeah, grilling somebody. Have you memorized these facts? I don't really even care about that. It's more about tell me what you think about this.

C: Yeah, can you critically think your way through this and can we all as a group come up with like better solutions?

S: Yeah, that's all great. But some answers are right and some are wrong. You know what I mean?

C: Right. That's true too.

S: Or some are better than others and it's OK to acknowledge that without – but again, without judgment or shame. I mean that's the thing. You want to take all the shame out of education and you want to be nurturing but don't pretend like everybody wins and it's all good and there's no wrong answers. I mean that's a way overreaction that I think is extremely counterproductive. The world doesn't work that way.

C: And they're cognitive distortions. So this psychologist identifies three cognitive distortions. There are so many out there. We can slice and dice the pie however we want. We do it all the time on the show. But in this particular write-up, they identified three cognitive distortions. Negative filtering, so basically a parent going, it's too dangerous for my kid to go outside because what if they get kidnapped? But they're not thinking about how actually healthy it is for the kid to be independent, to be able to solve problems, to develop risk assessment skills, to experience joy. They're only looking at the negative consequences of things. So we've got to be careful that we also look at the positive. They also identify the just – and we basically touched on this without saying it explicitly, dichotomous thinking. Either that thing is good or that thing is bad. I'm sorry. It's almost never that simple. There's always nuance. Things are good and – yeah. Like they have both.

S: Yeah. There's a good analogy to be drawn to the cleanliness thing, the idea that everything has got to be absolutely sterile. Kids don't get exposed to any germs because otherwise they'll get sick. It's like, yeah, but now you're hampering their immune system. It's actually a good thing to get – we don't want to – don't inject them with Ebola or whatever. But getting exposed to the normal background level of germs is a good and healthy thing. It's the same thing.

C: It's the exact same thing and the problem is that a lot of people listen to that rhetoric and they overcorrect and they want to inject their kid with mental Ebola. I think that's the other issue, right, is this argument that we don't want it to be so sterile. But we need to let them live in the world. We don't need to toughen them up. We don't need to force dangerous or negative experiences on them to, "make them resilient". The world is hard. They are going to be facing cruelty, unfairness, difficulty every day of their lives just by virtue of being alive and being around other kids. So we should be fostering in them independence and security. Let's help them feel safe.

S: Exactly.

C: And the way we can help them feel safe is by knowing that there's a place that they can come, where they can talk to us when they're ready, when they want to and we can help them navigate those issues. It's not about protecting them from ever feeling anything.

S: Exactly. Don't shield them from the world. Give them the skills to deal with it.

C: We know how this works with like sex education. It doesn't. Like the evidence shows it doesn't.

S: Right. Exactly. All right. Thanks, Cara.

C: Yep.

W± Boson Mass (41:49)

S: Bob tell us about these shock bosons.

B: Interesting way to put it. But okay, researchers released an updated estimate of the mass of an important particle in physics called the W± Boson. That mass estimate is very close to what our best theories predict it should be and that just sucks.

E: Okay. Why? Because there's nothing special?

B: Why does it suck?

S: Because there's nothing to learn.

B: We shall see. First, though, what is a W± Boson? We've mentioned it a couple of times, but definitely a refresher would be nice. These particles mediate one of the classic four fundamental forces of nature, the weak force. They are said to carry the force like the photon carries the electromagnetic force. The weak force, though, in my eyes is the redheaded stepchild of forces. Is that expression not cool anymore? I actually don't know.

C: Me neither. I'm like, let's look into that.

S: It's probably racist on some level.

C: I don't know. I don't think it's probably racist. I think it's just more about like cheating.

E: I think it's inherited phallic-ist. It's something.

C: I don't know. Whatever. Move on. Move on.

B: The point is I don't think the weak force is on anyone's favorite force list and I, of course, most people should have a favorite force list because why not? So it's not cool like the strong force, which is basically the superman of forces, right? What's not to like about the strong force? The electromagnetic force is my favorite since it makes glorious light in all of its forms from gamma rays all the way to radio waves. It's always enthralled me since I was a kid. The final fundamental force, gravity, is just wonderful, right? It's distinct and mysterious and it shapes the universe itself. What's not to love about the gravity? Compared to them, the weak force kind of has an impossible task, right? But it is critically important beyond measure and fascinating in its own right. It's responsible for some types of radioactive decay, which drive the nuclear furnaces of stars and life as we know it just would not exist without it to name just a couple of ways that it's incredibly important. W± Boson's precise mass is actually pretty important too since it could help us refine and test what one physicist called probably the most successful scientific theory that's ever been written down, the standard model of physics, which I've mentioned many times on this show. It describes the fundamentals of the known universe at the beautifully basic level of interacting forces and particles. The model has been basically bulletproof for decades. It just shrugs off any theoretical onslaught that has tried to discredit it. It's amazingly successful. But the standard model's last major prediction, what was the last major prediction?

S: The Higgs boson?

B: I remember talking about it at TAM 11 years ago in 2012 and holy crap, that was 11 years ago. Damn. All right. So now we know the standard model is not complete though. As awesome as it is, it doesn't predict important things like dark matter or dark energy, the ever increasing expansion of the universe, and even gravity itself has never fallen out of the standard model's equations, not even mentioned in there. So clearly this is a partial model of the reality as we know it. So this is why when Fermilab's physicist reported the most precise measurement of the mass of W± Boson last year, it really caused a ruckus because it calculated a mass far more than what the standard model itself predicted. And this new measurement was compelling. It's not like they asked ChatGPT what the mass was. They actually worked with 400 scientists worldwide over a decade and they went through 4 million potential W± Boson particle candidates that were created by 450 trillion collisions at the Tevatron Collider. So they did some homework. They did some serious homework over 10 years. They also claimed that they had the most precise measurement yet to 1.01%, twice the precision of previous efforts. So now that was exciting. It was exciting and some people of course said, all right, calm down. This is still kind of like it's not definitive, but it was exciting, especially to me because it could mean that we finally found the chink in the standard model's armor. Such a large mass could mean, for example, that there's maybe a new particle or force out there that could be causing this extra higher mass than we anticipated. And that could be the first solid evidence of physics beyond the standard model, which I've been crowing about for many years, something we've been searching for. The big fear nowadays I think is that the energy regime that we would need to engage with in order to encounter new physics, maybe it's so far beyond humanity's technological prowess that it could be generations, decades or 100 years before we actually can build something that could illuminate new physics for us. That's the big fear. That we are now in a dead zone, a desert of physics, of particle physics, where the LHC or anything even much more powerful is just not powerful enough to reveal what needs to be revealed. So that's what's scary to me. It's like, oh man, no new physics for a really long time. So that's-

S: Bob let me ask you a question. So the "shock boson" that I talked about at the beginning was in the title of the paper or at least the recording of it. W± Boson? That's just a fancy way of saying the W± Boson? Or is that some- I thought it was some other boson they were talking about.

B: No, no, no. I think you just misread the title. Let me see.

S: There's no comma after shock. It's not like shock, boson result. It just says shock boson result. Why does it say that in the headline?

E: No money down. No, money down. (laughter)

B: Yeah. I mean just an unusual way for them to describe it.

S: But they're talking about the W± Boson. It's just bad headline writing. Okay. Go ahead.

C: It's like the Higgs. It's like god particle discovered.

S: Yeah, right.

C: Why?

S: It's the equivalent of a god particle. Gotcha.

B: Yeah. The new and disappointing bit now is the ATLAS collaboration at CERN's LHC, Large Hadron Collider. They've reanalyzed their own boson data that they took years ago and they've improved their estimate based on this reassessment. They improved their estimate of its mass. They say that their new estimate is 16% more precise than their previous estimate. Let me just say what these estimates are then. The standard model, right? The standard model predicts a mass for the W± Boson at 80.357 GeV or giga electron volts. So 80.357. Fermilab predicted it at 80.433 giga electron volts. So from 83-

S: Well, they measured it, not predicted it.

B: Yeah. They measured it. Their estimate plus or minus the error bars is 80.433. Our standard model was 80.357. So it's it's definitely heavier. The LHC ATLAS estimate puts it at 80.360, which is just a tiny bit above the 80.357 of the standard model. So they're really close, really, really close to what's predicted. So it just fits right in there. It's just really just a three, three thousandths of a GeV away. The Tevatron Fermilab numbers seem, they see, it seems close, right? It's just like less than one, right? But you know, it's still like 80, what is it? 80 thousandths of a GeV. That's a huge, that is a big difference. It seems tiny, but we the G and GeV stands for giga. I mean, this is, it's a lot, it's a lot. And it's, and that would be dramatic if it's true, because it's so different from the standard model. So this doesn't mean that the ATLAS prediction or the estimate is correct and Fermilab is wrong. There's nothing definitive being said here at this point. Fermilab proponents say that after all, the ATLAS number is a refinement of the earlier number, which was close to the standard model's prediction anyway. So nobody was really thinking that they were going to be dramatically change that estimate. So that's not really a huge surprise. That's kind of what Fermilab people are saying, as far as I could tell. There's also the fact that this new number is also their, it's their preliminary number estimate. It's not the official number yet, but of course, I don't think when it becomes official, it's going to be dramatically different than what they've already released. So the general consensus seems to be that the large mass estimate from Fermilab from 2022 seems less likely to be correct now, now that this new estimate has been released. People are definitely not as hopeful as they were before. But of course, time will tell with this one. Rigorous review is still needed to happen with the new ATLAS number. So there's always the chance that there's some kind of fundamental problem that makes their estimate unreliable. I guess that's possible. Then there's also other experiments in the near future that are going to refine even further. And there's even some proposed new electron-positron collider ideas that would be even better than measuring the W± Boson's mass because they'd be specifically created to do that very, very well. And so, yes, I'm disappointed that this new possible discovery of new physics is probably is less likely now, but we'll see once the vetting process is over what the experts are saying. And I'll still have hope in the future that we can see some brand new physics out there, at least something that will help explain dark matter and dark energy and gravity because the standard model is not doing that at all. So that's where I am.

S: So the standard model is still a useful tool, but a cruel tyrant at the same time.

B: It is. It is. And it's like, what is it, 94% of the universe has nothing to say about. Like, wait, what about all this extra stuff over here that we recently discovered? What do you say about that? I am agnostic. I say nothing about it. It's frustrating. And I just want some answers, goddammit.

S: All right. Thanks Bob.

No Health Benefits from Moderate Drinking (52:03)

S: Evan, is it helpful or isn't it helpful to drink moderate amounts of alcohol? It seems like this is an endless question.

E: Yeah, endless question. And certainly I think something perhaps all of us have heard or is in sort of common parlance that yeah, a little bit of alcohol, that's good for you. And a little drink of wine here.

B: For years, a little bit, just a drink a day or whatever.

C: Oh, resveratrol.

E: And if you go online. Yeah. If you go online and you actually go to some reputable places, they may actually back that up. I went to the Mayo Clinic website. Here's what they had to say about it. Under their header, pros and cons of moderate alcohol use. Moderate alcohol consumption may provide some health benefits such as reducing your risk of developing and dying of heart disease, possibly reducing your risk of stroke, possibly reducing your risk of diabetes. You can go to WebMD. WebMD has some things in which they say, oh, surprising ways alcohol may be good for you. If you're in good shape, moderate drinking makes you 25% to 40% less likely to have a heart attack, stroke or hardness or hardening of arteries. This may be in part because small amounts of alcohol can raise your HDL, which is the good cholesterol, raise your HDL levels. Okay. And there are plenty of other sort of reputable places you can go to to see similar stuff. And also, oh, by the way, in more recent times, wine, particularly red wine, developed a reputation for having health benefits because news stories have highlighted their high concentrations of a protective antioxidant.

C: Resveratrol!

E: Yes, resveratrol.

B: Oh yes.

C: I love that.

E: Resveratrol found in blueberries and cranberries, of course. We've talked about antioxidants.

B: Oh, my God. Why is that still in the news?

E: Did you know that this idea has been around for 100 years? It dates back to 1924. There was a biologist at Johns Hopkins named Raymond Pearl. Steve, didn't you go to Johns Hopkins?

S: I did.

E: Coincidence? I think not. But in any case, Raymond Pearl published a graph with a J-shaped curve. It had the letter J. So picture that in your mind. The starting point at the left side is elevated, representing abstinence from alcohol. Then the curve goes down, hitting the low point in the middle, representing the moderate drinkers who supposedly had the lowest rates of mortality from all causes. And then sure enough, when you get past that moderation, zoom, the curve rockets upward, signifying what we understand as heavy alcohol consumption, and it increases your mortality a lot and reduces lifespan. The effects of alcohol, they've been scientifically studied now for many decades. And while some research in that time has synced up with the moderate alcohol consumption can be somewhat healthy understanding that a lot of us have, but there have also been other studies that say the opposite's true, that there are actually no health benefits to any levels of consuming alcohol. Okay, so what's going on here? Well, there's been a new analysis published recently in JAMA Network Open, and they looked at more than 40 years of research, and they concluded that many of those studies which showed some health benefits for moderate alcohol consumption, they were flawed. Yep. The researchers analyzed more than 100 studies, which had 5 million adults within those 100 studies. And they were able to identify and correct for methodological problems that plagued many of the older observational studies. And these reports that they evaluated, well, the reports themselves consistently found that moderate drinkers, they're less likely to die of all causes, including those not related to alcohol consumption. That sounds good, right? But here's the thing, most of the studies, observational that they are, it meant that they could identify links or associations, but could be misleading and did not prove cause and effect. The scientists said that these older studies failed to recognize that light and moderate drinkers had a lot of other healthy habits and advantages, and that the people in the groups that they looked at who would abstain from alcohol, well, guess what? They were actually former drinkers who gave up alcohol after developing health problems.

C: Yep.

E: Yep. So basically, many people, the people in the study deemed to be the non-alcohol users are former alcohol users who have health issues.

S: Well, some of them are.

E: Some of them are.

S: Some of them are and it contaminates the data.

E: Enough so that, yeah, that it flaws.

C: But I bet you it's a pretty big percentage. I mean, I say this anecdotally as a non-drinker, and I know, Steve, that you don't drink either, but I say this anecdotally, and maybe it's because of my age and my cohort and all that, but when I'm out and somebody buys me a drink, offers me a drink, and I say, no, I don't drink, they always say, they always are like, oh, why? Like, you got a problem?

E: Oh, yeah, it triggers something.

C: So the assumption is that if you don't drink, it's because you had a problem with alcohol. And it makes me really wonder, like, what percentage of people out there just don't drink and never really did?

E: It's low.

C: I bet you it's quite small.

E: It's low. According to the researchers who actually did look at that, they said people who abstain completely from alcohol are a minority. I didn't read the study enough to find out the exact number, but they said absolutely, definitely minority of people fall into that category who are teetotalers, 100%. Yeah, former alcohol users, they already developed their health issues. At some point, they stopped drinking, but the damage was done. So if you're going to compare a group of already damaged non-drinkers to moderate drinkers, yeah, that's going to look like the moderate group is healthier, but that's not true. And Tim Stockwell, he's a scientist with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, and he was one of the authors on the report. He said that when he and his colleagues corrected for these kinds of errors, he said, lo and behold, the supposed health benefits of drinking shrink dramatically and become non-statistically significant. And there's other factors as well. Those who drink did have other health problems, and there's socioeconomic factors as well, people who struggle with disabilities who also drink. So there's a wider sort of group of people who drink for whatever reasons that they drink that they go on, and hence the people who completely abstain, relatively small group. Moderate drinkers tend to be moderate in lots of different ways, not just in their drinking, but they also have – well, they tend to be middle to upper class in a sense, wealthier. They have decent economic means. They're more likely to exercise, to eat healthy diets, and less likely to be overweight, and better hygiene including oral hygiene that they found. So the moderate alcohol hypothesis certainly has come under more criticism over the years.

C: Because there's not really a plausible mechanism. Really? They think it's the resveratrol?

S: That was the idea that it was something in the alcohol or alcohol itself like might lower cholesterol or whatever. But they've explored all these options and nothing really ever came of it.

C: And any benefit like that is like significantly outweighed by the risks of the alcohol.

S: Yeah.

E: That's right. And they say including just red wine, it can contribute to cancers, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, high blood pressure, and heart arrhythmia. So those are the things that the newer studies now, the better studies in effect, are finding that come along with studying things just red wine, not even the really harder liquors that are out there that people consume.

E: So Evan I have to say I heard this 15 years ago, the idea that the non-drinker cohort was contaminated by former drinkers. So this is not a new idea. This problem with the observational data as a confounding factor has been around for a long time, at least 10 to 15 years. So I'm not surprised. It's always hard to do these kind of observational studies because it's really, by definition, it's hard to control for confounding factors. And this has been this sort of back and forth open question for decades. So this is like just the latest salvo in a long story. You know what I mean?

C: Right. Because clearly a lot of the researchers who are continuing to do these studies didn't get that memo. And so there's like 10 to 15 years of more research to be looking at these meta-analyses of or just these studies basically in general of to have to then re-debunk, which is frustrating.

E: Well, right. Because it's in the social conscious right now that exists. Most people believe that there are no negative health consequences with moderate drinking.

C: And maybe even positive ones.

E: Right. And some positive effects.

S: The public consciousness is different though than researchers who should be up on the literature. I think they mostly are. I just think it was just not a completely closed question. And some of them may have missed the memo, Cara, as you say. Like they didn't realize that this issue was already brought up before. Because this is a complicated area of research. But yeah, I wasn't surprised to see this at all. That's basically what I've been assuming for the last 15 years since I read the earlier summaries of the research. Yeah, once you factor out the non-drinkers, the benefits all go away.

C: I literally, I got in an argument the other day with somebody because I drank a Coke in front of them.

E: Oh no.

B: How dare you.

C: Like a Coke. And they were like, oh my God, it's so full of toxins. It's so bad for you, blah, blah, blah, blah. Which don't get me wrong, it's way too much sugar. It's not healthy to drink all that sugar. Right? I was drinking a full sugar Mexican Coke. It's my favorite thing in the world. Give me a vice. I don't have any vices. Let me have this. But he was like going hard. And I was like, you just drank two beers. I don't understand. And it's so funny. It's so common for me to hear this from people like, Mexican Coke, that shit will kill you. And they're like drinking alcohol right in front of me. And I'm like, that has almost the same amount of sugar and also is bad for your liver. How are we still having this conversation?

E: Right. Not to mention the inebriation effects on top of that.

C: Oh my gosh. I know. Beer is not a health food, people.

E: No, I mean, look.

C: I know Coke isn't a health food either, but neither is beer.

E: I don't know. What I've also heard, and I know we're off on a little tangent here, is that, what, in the Middle Ages maybe, the beer was healthier to drink than the water because you'd get dysentery from the water.

C: Part of the reason I got re on my Coke, my Coca-Cola problem is that I travel internationally so much. And sometimes, yes, Coca-Cola is healthier to drink. It's not healthier in the sense that it is good for you. It's healthier in the sense that you're not going to get an intestinal parasite or an illness from drinking that. Yeah, there are places in this world where you have to be careful. You can only drink water if it's been boiled. So tea, coffee, usually fine. Reconstituted juices, straight water out of the tap, not okay. So if you don't have bottled water in front of you, yeah, I'm going to drink a Coke.

S: All right. Let's go on. We're going to do, there's no who's that noisy because Jay's not here. So I'm just going to do one Name Not Logical Fallacy and then we're going to go on with our interview. We have an interview with the COO of Amprius, the battery company who had that exciting announcement. We're going to get into some technical details. It's a really fun interview.

Name That Logical Fallacy (1:03:06)

- AI sentience

My favorite segment of the show is Name Not Logical Fallacy, of course. I almost never get it right, but I think those discussions are super interesting and fun. I wish it was a standard part of every episode. Anyways, I listened to the recent AI debate with a fellow formerly from Google. He stated that the Google AI was sentient because it seemed to deviate from the parameters that had been defined to control its behavior. That sounds to me like the classic false dichotomy. You cannot explain something, so my explanation must be true. It's very similar to the argument you get from religion. Where and how did life arise? Science answers that. We do not know yet, and the religious debate immediately says you can't explain it, therefore Jesus QED. The conclusion is reached with no proof and no alternative is considered, even though a vast array of equally or more, or often more plausible mechanisms could be responsible. Thanks for the great show. Keep up the good work. And yes, I am signing up as a patron right now.

–Bob Compere

S: But first, this email comes from Bob Compere. C-O-M-P-E-R-E, Compeary, Compeer, Compear. I don't know. What do you think? "My favorite segment of the show is Name Not Logical Fallacy, of course. I almost never get it right, but I-"

B: Neither do we.

S: -"but I think those discussions are super interesting and fun. I wish it was a standard part of every episode." Well, we'll take it under advisement. "Anyways, I listened to the recent AI debate with a fellow formerly from Google. He stated that the Google AI was sentient because it seemed to deviate from the parameters that had been defined to control its behavior. That sounds to me like the classic false dichotomy. You cannot explain something, so my explanation must be true. It's very similar to the argument you get from religion. Where and how did life arise? Science answers that. We do not know yet, and the religious debate immediately says you can't explain it, therefore Jesus QED. The conclusion is reached with no proof and no alternative is considered, even though a vast array of equally or more, or often more plausible mechanisms could be responsible. Thanks for the great show. Keep up the good work. And yes, I am signing up as a patron right now." Thanks, Bob.

B: Thank you.

S: So what do you guys think? He sort of does a quick—he hits on a couple of logical fallacies in here. I'm not sure any of them are the false dichotomy, but he's getting close there. So what's the fallacy? So I'll say this. He's committing a fallacy himself, but you had to—

C: Who is, Bob?

S: Yeah, Bob. But you had to listen to the interview to know what fallacy he's committing. I'll give you a hint there. But let's first focus on this idea that this is the false dichotomy of if you can't explain something, this other explanation must be true. Is that really what a false dichotomy is?

B: No.

C: No, a false dichotomy is either or the only options.

S: Right. We see—getting sort of framing it that way, which it just shows you how you could frame logic to make it sound like anything. But so I think what he's really referring to is the false choice, which is a sort of false dichotomy. It doesn't mean that there's only—like it's either 100% black or 100% white. They're just saying, all right, we got these two options, and if it's not A, it's got to be B. Or so it is prematurely limiting the number of possibilities. But what he's describing also includes the argument from ignorance, right? We don't know what this is, therefore Jesus, right? You can't explain it, therefore Jesus. That's an argument from ignorance. That's not a false dichotomy.

C: And also to me the biggest—and I actually use this term during the interview, I think, if I'm remembering correctly. One informal logical fallacy that's used quite often is the burden of proof logical fallacy. It's saying that the burden lies not on the person that's making the claim, but on somebody else to disprove. And he fully committed to that logical fallacy. And I even called it out. Like, I think we're talking past each other because we're saying that the other has the burden of proof.

S: I agree with that. But to be fair to Blake, who's what we're talking about, he didn't say what Bob said he said. So there's a straw—his whole email is a straw man. Which I explained to him and he agreed once I explained to him. So what Blake was saying was that—yeah, so I agree that Blake was sort of shifting the burden of proof a little bit. But it was really—when we pushed him, what he says is, listen, what I'm saying is that the behavior of LaMDA, the AI that he was querying, can be explained if it were sentient. And that doesn't prove it is sentient, but I think that Occam's Razor favors that explanation. And the alternative is solipsism.

C: And he did make that argument.

B: That's where he was wrong.

C: And I think we should get into that. But to be fair, he also did say multiple times, I think that sentience is the best possible explanation and Google has not given me another explanation.

S: I agree. I agree.

C: He kept pushing the burden of proof onto Google.

S: Right. And when you pushed him, then he said, yeah, but Occam's Razor and solipsism—

C: Right. That was like his secondary.

S: So that's why we had to destroy those logical pillars of his position. Nope, Occam's Razor doesn't favor your position. And no, it isn't solipsism because we're not just saying that I can't prove something else is sentient based on its behavior. I could look at its architecture and say it's not functioning as something that is sentient.

B: That was his biggest mistake, I think.

S: Yeah, I think so.

B: For sure. That was one of his biggest mistakes.

S: So anyway, so I thought he—but he didn't say it has to be sentient because it deviated from its behavior. He didn't say it that way. That was a straw man.

C: He did say that there were potential other possible explanations. He just thinks this is the best one and he hasn't heard one that's better.

S: Yeah, I offered him one that's better. When I wrote about it the next day, because it gets always like you have to process the whole thing in your head and you get more efficient at explaining what my position is. I think the best way to explain it is that he was saying that this software, which is basically designed to mimic sentience, was actually sentient. And it wasn't just mimicking sentience really well, even though that's what it was actually programmed to do. So obviously, Occam's Razor would favor saying, well, this program that was meant specifically to mimic sentience is mimicking sentience. The other thing is, I think the explanation for the deviated from its programming explanation is he basically gave the answer. He said, the software is programmed to please you. It's also programmed not to discuss religion. So I pushed one parameter—

B: One of them went out.

S: Yeah, I pushed it until it broke the other one. He said that's what he did. I kept pushing it, pushing and pushing, the shaming and whatever, the please me angle, until it overrode the don't talk about religion imperative. So of course it did. You pushed it until it broke. It had two conflicting directives, and you pushed one until it overrode the other. That's the explanation. It doesn't have to be sentient in order to explain that.

B: That's why HAL killed people.

S: Yeah, that's exactly right.

E: Yeah, that is true.

S: He was given conflicting instructions, and he went a little cray-cray. All right.

C: But he also wanted to? No?

S: Well, no, no.

C: I'm not going to get into that.

S: So in 2001—

E: Here we go. Cara, you did it.

S: Bob did it too. You can't bring up 2001 and not have me talk about it.

E: Yeah, we can't walk away from this.

B: It's more 2010.

S: Well, no, you're getting to my point. In 2001, it's completely ambiguous. We don't know why HAL 9000 breaks. That's kind of the point, is that we don't know why.

C: It is kind of the point, but we're also meant to feel a certain kind of way.

S: Yeah, you kind of feel sorry for him at the end. But then in 2010, they explained it all. And some people think that they shouldn't have done that. It was better to leave it.

E: Yeah, it's like, oh, midichlorians are the force. Really?

B: Aaaaah!

E: Crap.

C: For me, my version of that is—

B: The most egregious example of that.

C: -that's so off topic, but my example of that is Pan's Labyrinth. I just wanted to know—it should have been left open. Is this a place she was going in her head in order to escape the brutality of war? Or was the fantasy land actually real? And I don't think they did a good enough job. I feel like they buttoned it up too well at the end of that. I wish they would have left it open. Sorry.

S: Unlike Total Recall, where it was wonderfully ambiguous whether or not he was really in a psychotic break or in a simulation or if he really was a sleeper agent that was got-

B: Well, it was wonderfully ambiguous, but I think there was one big tell that kind of decides it.

S: Yeah, I agree.

B: Yeah, we've talked about this in the past.

E: Should I mention Highlander or is that going too far?

B: Oh, my god.

E: Same idea.

B: And Steve, you said HAL was cray-cray, but I think you're wrong because HAL was not based on the cray supercomputer architecture.

S: Yeah, you're right.

E: Clever, Bob. Very clever.

B: Thank you. Thank you.

S: All right, let's go on with our interview.

Interview with Jon Bornstein (1:11:41)

- Electronic Weekly: 500Wh/kg and 1,300Wh/litre from lithium ion cells[1]

- Amprius: The All-New Amprius 500 Wh/kg Battery Platform is Here

S: We are joined now by John Bornstein. John, welcome to the Skeptics' Guide.

JB: Thanks for having me.

S: So John, it says here that you are the chief operating officer for Amprius Technologies. We spoke about your press release from a couple weeks ago, and I wanted a lot more information than I could find online, so you kindly agreed to come on the show and answer our many pesky questions. So why don't you tell us first, what's the deal with this new Amprius 500 watt-hour per kilogram battery that you have?

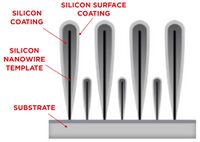

JB: So Amprius has developed and is shipping product for high-performance applications. The product is lithium-ion cells, and the fundamental differentiator is the silicon anode. We have a unique silicon anode that enables very high energy density. Silicon has 10 times more capacity than carbon, which is the incumbent material in everybody's lithium-ion cell, the one that's in your cell phone, in your car, in basically anything that is running on batteries today. And as a result, if you can do it right, if you can solve the fundamental problem of silicon, then you can exploit tremendous advantages in energy density. And so that's what we've done. We've solved a fundamental problem, which is that silicon swells when it's charged with lithium, and after a few charge-discharge cycles, that swelling leads to essentially cracking. And cracking means that you're no longer passing charge, and your battery's dead. And that has limited the sort of deployment of silicon. And there have been a lot of efforts to overcome that, and we overcame that with a concept that came out of Stanford University in around 2006, 2007. And then we perfected it and have a product that we're shipping today.