SGU Episode 601

| This episode needs: transcription, proofreading, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 601 |

|---|

| January 14th 2017 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

D: David Gorski |

| Quote of the Week |

It is when we are most desperate that we are at our most vulnerable. It’s hard to be objective, to ask for the evidence, and to critically appraise it. But that’s when it’s probably most important. |

Scott Gavura, Bad Science Watch (Canada) |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

- Cara is back from Hawaii

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

What's the Word (1:14)

- Parallax

S: All right, Cara, we'll start us off with a What's the Word.

C: Yeah! So, the word this week is a fun one. I know it's probably one of Bob's - I don't know, Bob. Is this one of your top words? Parallax?

B: Oh yeah. Parallax (inaudible) baby!

C: It's such a good word.

B: It's awesome stuff.

C: Yeah. All right, so according to Merriam-Webster, we'll start with that, a parallax is the apparent displacement or the difference in apparent direction of an object as seen from two different points that are not in a straight line with the object. So that's a little bit jargony, but we'll dig into it. Especially the angular difference in direction of a celestial body as measured from two points on Earth's orbit. And of course, that's where parallax really becomes important, I think, to us in science.

So, a good kind of example of this is, it's kind of like triangulation, right? How are astronomers able to estimate the difference of objects in space, knowing that Earth is on a course around the Sun. So, what they do, is they measure the star's movement against the background of more distant stars over the course of that movement around the Sun. And by looking at that difference, they can get a better idea of exactly how far apart those things really are.

A good kind of cheap and dirty way to play with this method is the same way that - have you guys ever done this - where you have obviously one dominant eye, and you can test which eye is dominant

B: Yes

C: if you hold your finger over something in the distance. You close one eye, and your finger stays in the same spot. You close your other eye, and the finger seems to jump a little bit.

J: Yep. Yeah, it does that all the time.

C: That's very similar to what we're talking about with parallax. We have to be able to triangulate that difference to know exactly where your finger is, because your eye's in two different positions, to be able to figure it out. The cool thing about parallax, I think, and what Steve brought up to, is parallax's relationship to parsec.

B: Yes!

C: So let's first talk about the etymology of parallax. It's from middle French - parallax - in the 1570's, which goes back to the Greek parallaxis before that. It refers to change, alteration, inclination, and even before that, you can kind of break it down into para and allxine, which is, yeah, also Greek, which means to change. Similarly, when we look at the word parsec, which, you guys know what a parsec is, right? That's a unit of measurement.

S: Yeah

B: 3.26 light years. Parallax second.

C: There you go. And that's the thing. When we think about astronomers, and how they actually talk, they don't usually really use light years that often. They actually talk in parsec.

B: Well, not even parsecs, really, I would say. You hear things like megaparsec, gigaparsec, really vast distances in space.

C: That's true. Yeah, so just like you said, Bob, a parsec is a unit of measure for interstellar space that's equal to 3.26 light years. It's the distance to an object having a parallax of one second as seen from points separated by one astronomical unit.

B: That's a good way to put it.

C: That's really where the word comes from. It actually was first coined in 1913, and if you break down the words parallax and second, and you take the first syllable of each, it becomes parsec, which I think is so cool! And I'm not sure what

B: It's a cool word.

C: people

B: It's just a cool word.

C: know about that connection, between

S: And do you know, Cara, why they use AU as the baseline?

C: The astronomical unit?

S: Yeah

C: I'm not sure. Why would they use that?

B: Eath's orbit, right, Steve?

S: Earth's orbit! Because what we're

C: Yeah, there you go.

S: doing is look at stars at one point in Earth's orbit, and then comparing their positions when observed a time of the year when the Earth is in a different point in its orbit. So basically, we're using the movement of the Earth around the Sun to generate the parallax, right?

C: And so just like the genius that is the metric system,

S: Yeah

C: it's always easier when you base it on kind of that single unit of one.

S: Yeah

B: And for close stars, you could then, you know, make a really skinny triangle, and you could actually find the distance very, very accurately. And unfortunately, that only works for very close stars, 'cause once you get a certain distance away, then the parallax is so tiny that you can't even measure it. And then you need standard candles.

S: Yeah

B: And that's where the standard candles come in, like cepheid variable stars, and supernovas

S: Yeah, type 1A supernovas.

B: which gave us the, yeah, the increasing expansion of the universe, so,

S: Yeah, parallax

C: That's cool!

S: is good to about a hundred parsecs, which is about three hundred and twenty-six light years. That's about it. Beyond that

B: It's so tiny.

S: It's too tiny to measure.

B: Too tiny to measure.

S: Yeah

News Items

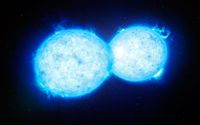

Colliding Stars (5:52)

Countering Fake News (11:36)

S: All right, well, we've been talking a lot about fake news, and disregard for truth, et cetera, and you know, a lot of people have asked me, "What can we do about it?" And it's really, at this point, it's not really clear. I know Facebook is trying to change the rules by which they promote news items. But Jay, you're gonna tell us about maybe some other ideas about what we could do to combat the epidemic of fake news.

J: Yeah, not too long ago, November of 2016, an environmental science professor named Nathan Phillips noticed that the news site Breitbart news had

C: Breitbart (bight-bart)

J: an ad on their site. Right, bright-bart, whatever.

C: Bright-bart, yeah.

J: I like to mispronounce these assholes' names.

(Laughter)

J: Breedle-barden News, what happened was he noticed that an ad was on Breitbart news, thank you, for Duke University, and other universities. And since he actually, he received his degree from Duke, he realized that Duke University officials probably did not know their ads were appearing on that website. And he asked himself a very simple question: Why would an environmental science program at Duke want their university promoted on a website that denies the existence of climate change!

So, to further explain, just so you guys get the big picture here, Duke University, as an example, pays to have its ads shown all over the web, right? They want people to go to their university. So they pay a company to distribute their ads, and you might see them on one of hundreds of websites that you visit. You know, a little banner ad, which we all are very used to seeing, even in the middle of, say, blogs that we read, or whatever.

So, Breitbart displays these paid ads on their site, and they make good money doing it, since they got a ton of people that visit that site every day. So indirectly, they, Breitbart, is making money off of Duke University. Not directly, but absolutely indirectly through the intermediary company that places the ads.

So Phillips contacted Duke, and after some back and forth, Duke assured him that their ads were not going to appear on that news aggregator site any more. So what he did, in essence, was become an activist, and he took action against misinformation in fake news.

Now, unrelated, around the same time, a company, or I shouldn't even say a company, an organization started to send out thousands of tweets that were contacting companies, to let them know that things like this were happening. Now, they call themselves "Sleeping Giants," and they actually have done a remarkable job in a very short time, since last November, to contact these thousands of companies, and over four hundred of the companies that they have contacted had responded saying that they are going to remove their ads from this site and other sites like it.

That is awesome. And it is a very simple way to fight back against the fake news. And the cool thing about this is anybody can do it. And now, what they say is all you need to do is take a screenshot of the ad on, say, that or any kind of news aggregator site that you feel is compromised, take a screen shot, especially if the ad is next to a piece of fake news, or something bad, you know, something that is either poor journalism, or something that you feel the organization would be upset about, and you tweet it.

You know, this is starting to snowball. I am reading about other people doing it, and it seems to be one of the very easy things that people can do. You can spend fifteen minutes hunting and pecking around, and you put a post up on Twitter, and companies want to respond to this type of thing.

Now, I happen to work for a global company, and we are very cautious about lots of things that happen online. We want our customers to be satisfied with our products, and we listen to, and read our reviews very carefully, and we respond to them. It's very typical for companies like this that consider their company a brand, to be very cautious with the brand, and how it's perceived. And I think that on top of that, executives at the companies are actually upset when they find out facts like this.

So, I put it to you as an SGU listener, someone that care about the truth, and someone that cares about not spreading misinformation. If you feel like you have any free time, on any average day, during your lunch hour, or whatever, why don't you take a look, and see if there's anything you can find that you think, "Hey, maybe this company would like to know that their ad is being displayed on this website, or alongside this horrible news." Take a screenshot, and tweet it, and see what happens.

C: Cool

S: Yeah, it'll be interesting to see if that kind of effort has any net effect. 'Cause you know, my fear is always that anything that we try to do for quality control, they'll just turn it around, and use it to fight back against the people who are calling them out on their bullshit, right? So the moment the term "fake news" was applied to actually fake, manufactured BS, the people who were spreading the BS immediately turned around and called anything they disagreed with "fake news."

J: Yeah

S: You know.

C: But I think there is a lot of power in advertising. You know, it really is, in many ways, a driver of our economy. And we've seen this happen a lot where, again, this happens more in traditional journalism. But where a traditional journalist may have done or said something that advertisers feel like is outside of ethical boundaries, or something that they don't want their brands associated with, and they'll pull their advertisements, and that person will get fired, because they can't keep their show afloat.

J: Yeah

C: Like, this does happen, so it is an interesting way to try and undermine that, using capitalism, like, kind of for good, I guess. (Chuckles)

S: Using market forces, yeah.

C: Yeah, that

J: I think the science and skeptical activists, and people that are advocates for these things, like our audience, I trust these people more than I trust the average person out there, because we like to educate ourselves about science and critical thinking.

S: Yeah

J: So, I think we're the right people to be doing this. You know, again, don't be a dick. I would say the company will absolutely respond to a polite and nice and concerned note over something like, "Oh god! Can you believe this jerk company is putting their ads on this site" or whatever. And a lot of times, of course, I'll remind you, a lot of the companies don't know where their ads are showing up. And they do have the ability to go into a back-end system, and limit where their ads are distributed to.

But most of the companies don't do it, because they're like, yeah, just get the biggest reach that they can, and they're not really thinking, "Oh wait! What site is this actually gonna show up on?"

S: Yeah, there's a lot of automated advertising.

C: Oh yeah.

S: And I think the article, Jay, that you're referring to, estimated that there's like, twenty-two billion dollars in ads every year that are just programmed. No one's deciding exactly what's going where, it's just happening automatically.

J: Absolutely! I mean, as an example, some of the ads you'll see on our sites, you know, we have a service that pays us to display those ads, and I can go into the back end system, and edit out ads from companies that are showing stuff that we really don't want to. The problem is, and I think everybody knows what I'm about to say, is that the vast majority of the ads that come through a lot of these companies are kind of junky.

S: Yeah, they're mostly clickbait, yeah.

J: It's clickbait junk food. You know, and it is a way for bloggers, and people like us to make some type of cash flow to help us pay the bills. And I do think it has its place, but you know, lines do get crossed. I see ads on some of our blogs, and I'm like, "You know, I don't like that." And I'll

C: Um hmm

J: get rid of it. But other things, and new things pop all the time. It's kind of like whack-a-mole.

S: Yeah

C: Yeah

S: Definitely.

Relaxing Music (19:20)

A New Organ? (26:39)

Who's That Noisy (38:59)

- Answer to last week: Whistling Language

Questions and Emails

Question #1: Dino Tail in Amber (43:57)

Great work covering the dinosaur tail trapped in amber, and I really enjoyed the interview with Brian Switek. I emailed once before; I co-host the dinosaur podcast 'I Know Dino' with my wife and I have a few more details about the dinosaur tail discovery I thought you might find interesting: To your question of how they know it wasn't a fake -The amber from this region in Myanmar actually fluoresces a characteristic blue when bombarded with UV light, which makes for a convenient way to authenticate it. To the question of whether some sort of scientific review could be put in place for Myanmar amber deposits -The area in Myanmar where the amber is found isn't currently controlled by the government. It's under the control of the Kachin Independence Army which effectively prevents regulation of Burmese amber in the region. As a result, scientists have to go to the market independently and purchase the amber there. But the government is hopefully that they might regain control through negotiations soon. Just an awesome side note -They also published on 2 wings found earlier, and mentioned in an interview that they collected 9 more specimens which apparently haven't been published yet. http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2016/160628/ncomms12089/full/ncomms12089.html Keep up the awesome podcast! I've been a happy member for years now :) And if you ever want to talk dinosaurs we'd be happy to help! Sincerely, Garret Kruger

Interview with David Gorski (46:11)

- http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/anti-vaccine-nonsense-at-cleveland-clinic/

- https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/trump-meets-with-rfk-jr-to-discuss-vaccine-safety/

Science or Fiction (1:15:05)

Item #1: A new study finds that exercising only on the weekends, compared to being inactive, has no measurable benefit in terms of heart health and mortality. Item #2: Scientists have genetically engineered a Salmonella bacterial species to seek out and destroy glioblastoma tumor cells and have successfully tested the treatment in rats. Item #3: The Hubble Space Telescope has discovered a probable new exoplanet using a unique method – by imaging a shadow cast upon a ring of dust surrounding the parent star.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:36:16)

'It is when we are most desperate that we are at our most vulnerable. It’s hard to be objective, to ask for the evidence, and to critically appraise it. But that’s when it’s probably most important.' - Scott Gavura, Bad Science Watch (Canada)

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References

|