SGU Episode 539

| This episode needs: transcription, proofreading, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 539 |

|---|

| November 7th 2015 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

Science has proof without any certainty. Creationists have certainty without any proof. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

- Star Wars viewing party. New Star Trek coming out.

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

Forgotten Superheroes of Science (3:24)

- Andrea Ghez: is an Astronomer and UCLA professor. She was voted one of the top 20 scientists in the US and studies stellar motions near the Milky Ways' supermassive blackhole

S: All right, well, Bob, tell us about this week's Forgotten Superhero of Science.

B: Yes, for this week in Superhero of Science, I am going to cover Andrea Ghez, who is an astronomer, and UCLA professor. She was voted one of the top twenty scientists in the US, and studies stellar motions near the Milky Way supermassive black hole.

Ghez was one of those kids that was just so cool. She would stay up late at night, and look at the stars, and think very profound questions like, “What does the beginning and ending of time? Where is the edge of the universe? And how do you come to terms with humanity's insignificant hundred-thousand year old existence, when being faced with a universe that's thirteen billion years old. Great questions for anybody to think of, really. But when a kid thinks about stuff like that, I just love it.

And I guess she never really stopped thinking about it, 'cause now, she is a world-class observational astrophysicist and professor of astronomy at UCLA. Now, as I mentioned, Ghez was voted by Discover Magazine as one of the top twenty scientists in the US who's shown a high degree of understanding in their fields.

And she's got just a fantastic job. She studies what is arguably one of the most fascinating areas of space within millions of light years. Guys?

S: The galactic core?

B: Yes! The center of our galaxy, which houses our very own supermassive black hole,

E: Nice

B: called Sagitarius A-star.

S: And according to Star Trek, that's where God lives.

(Rogues laugh)

E: Oh, that's right! Almost forgot that painful memory – thanks Steve.

S: You're welcome.

(Cara chuckles)

B: And she works at the famous Twin Keck telescopes, which are at her disposal in Hawaii. And they use adaptive optics, which is so cool. And that gives her the best view of that area of space, probably more than anyone ever has. Using it, her and her team have discovered multiple stars orbiting close to our black hole, including what's called SO-102, which orbits the black hole at a record-breaking eleven years.

The previous one was like, fifteen years and change. This star has the shortest period of any star orbiting. And it orbits at one percent the speed of light.

S: That's fast for a star.

B: That's ... absolutely! So its cosmic year is eleven years, and our cosmic year is ... what.

S: Oh, it's like two hundred and fifty million years or something?

B: Yep

C: Wow!

B: A quarter billion years, very good.

E: A quarter billion years, yep.

B: So these measurements that her and her team make, contribute to what is now the undeniable evidence that supermassive black holes do indeed exist, and that ours has a mass of about four million solar masses.

J: Whoa!

E: That's ... massive.

B: Fascinating research, fascinating woman. So, remember Andrea Ghez. Mention her to your friends, perhaps when discussing stellar velocity dispersion of a galactic bulge.

S: Galactic bulges are cool, although I can't help – this is one of those irrational things that I cannot purge from my brain – I could never help being a little scared of really massive black holes, you know what I mean? There's just something scary about the idea of something that big, with that much gravity, even though I know rationally I have nothing to be worried about.

B: You're silly.

(Rogues laugh)

B: It's so – yeah, that's common belief, actually, that, “It's gonna suck up everything!” It's like, well, it's so far away, that it's so irrelevant, how intense the gravity is. And you want to hear some really freaky shit? When you're talkin' really supermassive black holes?

(Evan chuckles)

B: If you were at the event horizon, you wouldn't really even necessarily even notice it. The tidal forces aren't anywhere near what they would be at the event horizon of a stellar mass black hole. And how about this? Their average density could be less than water.

C: Oh, crazy!

B: Yeah, it's kind of counter-intuitive, but that's what the math says.

E: So you could get close to the event horizon, and not get drawn in? It can go up to the edge? Theoretically.

B: Well, it's, the gravitational pull could be intense, but the tidal forces wouldn't necessarily be intense, because you've heard of spaghettification,

E: Sure

B: the tug on your feet could be thousands or millions of times greater than your head, which kind of turns you into spaghetti. You wouldn't see those types of tidal forces until you got very close, well within the event horizon. But yeah, the gravity would be intense, but you wouldn't be ripped into spaghetti. Probably just accelerate in very fast.

S: Yeah, you wouldn't be able to escape, you know, once you get to the event horizon.

News Items

Poop Power (7:46)

Parallel Universe (14:53)

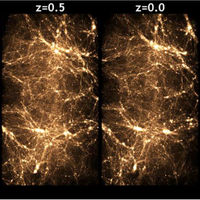

Whole Universe Simulation (22:53)

3D Printed Rhino Horns (29:33)

(Commercial at 39:30)

Special Report (40:56)

- http://westhartfordchurch.com/skepticsforum/

- Steve debated old earth creationists

Who's That Noisy (55:25)

- Answer to last week: vocaloid

What's the Word (58:41)

- Indolent

S: Cara, What's the Word this week?

C: The word this week is: Indolent. Anybody have a guess about indolent?

S: I know what it means, 'cause it's a medical term.

J: I don't know. I don't know.

C: So it is a medical term, so that's a good cue. But the really interesting thing about indolent – and I really like it as compared to some of my favorite words we've done so far, like stochastic and cannonical, because it means something different in the medical community than it means in its general use.

S: There's a lot of words like that.

C: Yes, and I love that. And I want to find as many as I can.

S: Yeah

C: So, in general, when you hear the word “indolent,” the general definition – it's an adjective, and it means having or showing a disposition to avoid exertion; slothful, habitually lazy, procrastinating, resistant to physical labor.

E: Hey!

C: So an indolent person is a lazy person. (Chuckles)

E: Describing me.

C: (Chuckles) But the medical definition seems to be completely unrelated – although it is not.

S: No, not really. It kinda makes sense.

C: Yeah, I didn't feel the connection right away, until I started reading about the etymology. But the medical definition is, “Causing little or no pain, inactive, or relatively benign,” like an indolent ulcer. It's not painful, it's slow to heal. So it's something that may be kind of happening in the background, and the patient doesn't even realize they have this indolent infection, or this indolent disease. And it's just kind of a slow burn.

S: Yeah, the disease is sluggish, and lazy.

C: There you go, the disease itself is sluggish and lazy,

S: Yeah

C: that's a good way to look at it. Yeah, and I never really thought about that, because the big thing that you hear a lot is that “indolent” actually comes from this idea of causing little to no pain. So the person has an indolent infection, or an indolent disease because they're unaware of it, because they don't feel the symptoms of it.

And so this is where things get interesting. If you look back to the 1660's, from the late Latin, “indolentum,” that translates to “painless.” And if you go even

E: Oh

C: further back, “indolence,” the noun, from 1600, means insensitivity to pain. From the Latin, “indolentia,” freedom from pain, insensibility. So, when you're like, “Okay, well it really comes down to an insensitivity to pain, or a freedom from pain,” so that makes sense, that indolent, in a medical context is that they don't feel pain. What does that have to do with being lazy?

Well, the sense of laziness happened around 1710, and it comes from the notion of avoiding trouble, or not wanting to take pains to do something.

S: Wow, take pains.

J: Oh!

C: Isn't that interesting?

S: Yeah

C: This was a very common expression, and that's where you start to see the crossover expression. So really, the etymology of this word does come from “pain.” And think about it: In-do-lent, spanish, dolore.

S: Yeah

C: Dolore abesa.

B: That's right.

C: You hear that “dolore” over and over, but if you don't take pains to do something, you are lazy.

S: Wow, that's cool.

C: Weird,

B: Cool

C: right? Isn't that fun?

S: Yeah, that's why language is cool.

C: It's so fun.

E: It is.

S: But I've always, in a medical context, I've heard it used much more often to mean just a very slow process, than without pain.

C: Yes, and I see that -

S: I think that's the more common use.

C: And I see that those two things probably have become sort of conflated, because so often, both of those things apply.

S: Yeah

C: And so, but yes. When I was talking – the reason this came up is because I have a friend who's visiting me, who's a newly minted doctor. And I was like, “Ooh! Let's think of a fun What's the Word this week together.” And she was like, “One of my favorite words is indolent. It's such an interesting, and very colorful adjective for a diseased state.” And yeah, it just means so much when you tell somebody that person has an indolent whatever.

S: Indolent tumor, indolent infection, yeah.

C: Yeah, or an indolent ulcer, you know, that they don't even know it's there, and that's really ultimately where that conflation came from, 'cause it started with not feeling pain, but still having a disease, very common with cancer.

S: Yep, yep yep.

C: Yep

S: It's true. Cool.

Swindler's List: Ransomware (1:02:37)

Science or Fiction (1:07:45)

Item #1: An examination of the medications used by astronauts on long duration missions aboard the ISS finds that the most common medications used are for anxiety. Item #2: A large survey of anti-vaccine websites finds that 2/3 of them use scientific studies to support their negative claims about vaccines, while 1/3 use anecdotes. Item #3: A new study suggests that supervolcanoes, unlike regular volcanoes, do not erupt because of a buildup of pressure in their magma chambers, and therefore require an external trigger.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:25:19)

'Science has proof without any certainty. Creationists have certainty without any proof.' - Ashley Montagu

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References

|