SGU Episode 438

| This episode needs: transcription, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 438 |

|---|

| December 7th 2013 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guests |

T: Tim Farley |

SG: Susan Gerbic |

| Quote of the Week |

The real advantage which truth has, consists in this, that when an opinion is true, it may be extinguished once, twice, or many times, but in the course of ages there will generally be found persons to rediscover it, until some one of its reappearances falls on a time when from favourable circumstances it escapes persecution until it has made such head as to withstand all subsequent attempts to suppress it. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

This Day in Skepticism (00:36)

- December 7: Happy birthday to psychologist Eleanor Gibson and deathday to Rube Goldberg.

R: Well, speaking of peoples' passing,

E: Uh huh

S: Mm hmm

R: Today is December 7th. On December 7th, 1970, the world lost Rube Goldberg, who died at the age of eighty-seven, Rube Goldberg.

S: Who died at the hands of a very complicated machine.

(Chuckling)

R: Easy joke, there.

S: I know! Someone had to say it.

J: We're just tryin' to warm up here.

E: Beat me to it.

R: Yes, Rube Goldberg was best known as the cartoonist who would satirize an increasingly technological world, using cartoons, with people using very complex machines in order to solve otherwise simple tasks. And you see influences, the people he influenced everywhere is a popular video by OK Go in the last couple years.

E: Oh yeah, that's an awesome video.

R: The new commercial for Goldieblocks that was just travelling around the interparts.

S: Wallace of Wallace and Gromit?

R: Did he do Rube Goldberg? I just

S: He was at the nerdy scientist who came up with these elaborate Rube Goldberg inventions in order to accomplish something very simple like

R: Okay

S: eating breakfast or getting dressed.

R: All I remembered is that he liked cheese.

S: Yeah

R: I'm not sure if Rube Goldberg did. There was the beginning of Back to the Future,

S: Yeah

R: in Doc's lab.

E: Sure

R: And the popular game when I was a kid, Mouse Trap.

E: Mouse Trap!

B: Oh yeah!

R: I have no idea how that game was actually played. All we ever did was just set up (chuckles)

E: Build it?

J: Yeah, me too.

R: Yeah, the trap.

J: And you do it like, a few times, and then that was it. You're done.

R: Yeah, yeah, then we were done with it.

B: Did you guys know that Rube, he won the Pulitzer Prize for political cartooning in '48?

E: Wow!

R: I did not know that.

B: A Pulitzer! Pretty impressive.

E: I spent a Saturday about a year ago just looking a couple of videos on YouTube. People and their own Rube Goldberg machines that they've come up with. I think I had spent about four hours before I looked

(Bob laughs)

E: at the clock and realized, "Oh my gosh! I've been watching these forever! They are mesmerizing!

R: Did you ever play The Incredible Machine? It was a computer game back in, I guessi n the '80's or the '90's. And it was addictive. It was building Rube Goldberg machines in order to solve problems. It was very open. I guess it was in the '90's. It was a lot of fun.

E: That sounds like fun.

R: The other notable thing for today was, I didn't want to just do a death day, so happy birthday to psychologist Elanor Gibson, who was born December 7th, 1910. Gibson is best known as being the person who came up with the study - she studied primarily perception in infants. That's what she's most famous for. And she's the one that came up with that study where she took a piece of glass, and hung it over a table ledge, basically, and put babies on top of it, and had them crawl across the ledge,

J: Oh yeah

R: coaxed by their parents. And many of the babies refused to do it. And that study helped show that infants have depth perception that informs their ability to stay out of danger. Also, a fun baby test to do. Make your baby think you're trying to coax him over a dangerous ledge.

S: Yeah, it's a trust thing. You know, it's like Abraham killing his son.

R: Is that what it was?

(Chuckling)

E: Wow! I didn't know we'd go all Bible

S: Just like that.

R: Yeah

S: Yeah, remember when God said, "Yeah, slice open your son's throat, you know?" And Abraham was like, "Really?"

R: Just as Abraham was about to do it, God's like, "I guess babies don't have depth perception."

S: Psyche!

R: "What a bunch of morons! Here, slit a goat."

(Laughter)

News Items

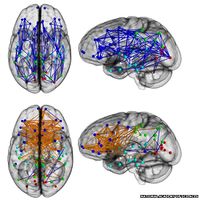

Male-Female Brain Wiring (04:27)

Wormholes and Black Holes (21:31)

Home Genetic Testing (29:14)

Who's That Noisy (39:46)

- Answer to last week: Bjorn Lomborg

Interview with Tim Farley and Susan Gerbic (44:00)

S: Joining us now are Tim Farley and Susan Gerbic. Tim and Susan, welcome to The Skeptic's Guide!

T: Thanks for having us!

SG: Hello!

S: And for those who don't know, Tim Farley is a research fellow for the James Randi Educational Foundation; the creator of the website WhatsTheHarm.net, which we mention all the time on the show; and also blogs about internet techniques for skeptics at skeptools.com.

Susan Gerbic is the co-founder of the Monterey County Skeptics; a member of the Independent Investigations Group; and the founder of Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia, and the World Wikipedia project, which is what you two are here to talk about tonight. So, Susan, why don't you give us an encapsulation, what is Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia?

SG: Well, Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia is a little over two years old. I started it because Tim said it was a great idea. Wikipedia is the source of all of knowledge, and we decided that we need to improve skeptic pages, create pages, create skeptical content, because it's very important that the world is able to get great knowledge.

So we've been working on this in many different languages for a little over two years. Now I have a forum that we can discuss all the page edits; we can train; we can create videos; we can create commercials for our podcasts; we can create podcasts. It's a little world, a little empire, that we have, that I'm always looking for new recruits, especially people who can speak and read and write in other languages.

S: So, why does it take so much effort to edit Wikipedia? Back in the day, you could just sign on there and start editing away. But that's not the case any more.

SG: Oh no! You can easily do that. But what we want to do, is we want to train, we want to make sure that people are editing correctly. There's a lot of rules. They call it “biting”. Some of the older editors might bite some of the newer editors who come in and try and make changes.

So we really want to coddle, I guess, our editors for a little bit; make sure that they know what they're doing; understand the process, so we can follow the rules; as well as, maybe put more focus on things that need to be done.

We're very critical about how we edit pages. When we roll out a page, it has seen many, many eyes before we release it to Wikipedia.

T: Yeah, what I've seen in the past when I've pushed Wikipedia on skeptic forums and stuff, is I occasionally get skeptics who are, “Oh! I tried to do that once, and they took the edit I put in out immediately.” What's happened over the years is if you remember from the early days of Wikipedia, when it first started, they were desperate for material. And it was super-easy to add stuff because they wanted to get articles written as quickly as possible.

But as the thing's grown up and attracted attention, they have to be more careful about what gets added, and what gets left in, and what gets taken out. So all these various rules have come up about reliable sources, and secondary sources, and things like that. And they tend to bite you if don't take a little bit of time to learn the rules and go slow at first. I found a lot of skeptics jump in there with both feet, and then get their fingers burned, so to speak.

S: Yeah.

T: Then they say, “Oh! Wikipedia's not interested in it.” And it couldn't be further from the truth. If you actually take the time to learn the rules, you can be very, very productive on Wikipedia. And the rules are actually pro-skeptic. They're oriented toward scientific evidence and scientific consensus, and there are rules against putting in fringe, crackpot theories; and stuff gets taken out all the time because there's no evidence for it.

S: So, they have some standard of scholarship now,

T: Yeah

S: to back up the edits. And when you say the old editors might bite you, you mean that they'll just remove the work that you did.

SG: Or they'll slap you down with some snarky comment that makes you not want to edit Wikipedia because they're … they use a lot of jargon, and it takes a little bit of time to learn the jargon, even though they're constantly giving you the links to what the jargon means. It's like a different world. It's not difficult to edit Wikipedia. The links and – it's not like learning a whole new computer language or anything like that. It's not difficult. It's just a culture.

T: Yeah.

SG: And it can be kind of overwhelming to people at first. So I coddle them. Like I said, we really, really, we practice. We start with spelling errors; we start with grammar; we start with adding periods, taking periods out, removing citations, putting in small things. And then everything's done in our user space, offline, where it's not seen by the general public. And we look it over and look it over, and people critique it, and we look it over again. And then when it's finally released, it should be done in good quality and good scholarship.

J: So, do you use that as a way to get your name recognized by the other editors so they don't jump on you in the beginning? You're just making the minor tweaks to get a level of familiarity?

SG: Well, sort of. You really need to build a history. And you don't want to just jump in and just start editing because that's a little suspicious. It kind of sounds like you're coming in with an agenda. So we do ask that you start with a history of small edits. It does look good, because it looks like you're trying to improve Wikipedia overall, and not just some specific person's page.

T: Yeah, and that exact thing has happened in the recent unpleasantness where people have come in, and suddenly started full speed editing one article. And it's always a red flag when somebody comes in and they're just editing this one article repeatedly and over and over and over. The other people on Wikipedia are wondering, “Are you interested in Wikipedia at all? Or are you just interested in this one article.”

S: What if you have an expert who has very narrow area of expertise, and that's the one article that they're looking to update?

T: They don't, it's not immediately, they don't immediately slap you down, if you're putting in the footnotes, and following the rules of documenting your work, you'll be fine. But it is something that sort of sets you aside.

So one of the things I always tell, and Susan tells her people, and I tell people, is if a skeptic wants to get involved, don't just edit skeptic stuff. Try to find some other things that you're interested in, Star Trek, or nanotechnology. I do a lot of stuff about buildings, and historic stuff here in Atlanta.

B: Good choices.

T: So there's a historic building that's used as a concert venue, and I wrote a whole big, long history of the building because it's a one hundred year old building. I wrote that for Wikipedia, and it helps build up your history, and people see that you're interested in Wikipedia, and not just trying to push an agenda.

S: But it is still true that anybody can sign up to be an editor and start editing.

T: Yup.

S: It's just that it'll be hard unless you know the culture and you build this history.

T: Right.

S: So, for the skeptics out there who want to make the world a better place by adding their edits to Wikipedia, is there a primer, or some place they could go where they could get a one page, sort of, “All right, this is what you gotta know if you want to be a Wikipedia editor.”

T: There is a couple places. I've got some blog posts on my site, at skeptools.com, there's a Wikipedia link right at the top of the page. If you go in there, there's a whole bunch of articles I've written. There's a couple of “Starting up, here's how you set up your account. Here's how you do simple edits,” like spelling changes, and reverting vandalism.

And then Susan has taken it a lot deeper; and she's done a bunch of videos on YouTube with much deeper stuff about how to do different types of edits, and what they're doing with the Guerrilla Skeptics.

S: Now, this all came up – the reason why we're getting you guys on the show now is because of Rupert Sheldrake and Deepak Chopra have been complaining about you guys.[1]

T: Yeah (laughs)

S: They're trying to portray you as skeptical vandals going in and spreading your skepticism through Wikipedia.

T: That's very interesting. I've actually spent some time going back through the blog posts, and going back through the histories of the articles in Wikipedia. And all their posts about it are amazingly evidence-free, which is striking with Wikipedia, because Wikipedia's very, very open. The history of every article is there. You can see every single edit to every single article all the way back. You can see every edit that individual editors have made. You can see the hit counts on articles. You know which articles are popular, and which ones aren't. You can see all the discussions all the way back to trivial discussions that were had six years ago about editing two words in a sentence. They're all there.

So there's plenty of information about who's editing it, and when they're editing it, and why they're editing it. And none of these posts by Sheldrake or Deepak have dug into any of that! Yet they somehow latched on to Susan. Basically it all boils down to a blog post way back in March, by Robert McLuhan. He's a spiritualist / psy type person who's written a book about The Million Dollar Challenge that's apparently very critical of Randi.

He blogged about Susan's project; and it wasn't especially angry blog, but he pointed out some things in Wikipedia that he didn't like, and said some things about, “Well, maybe we, the psy-believers should be getting our own group together.” And it was there that Sheldrake picked it up. Sheldrake mentions McLuhan in his first blog post, which was on June twentieth.

Actually, this afternoon, I went back and looked at the history of Sheldrake's article. And until McLuhan, and Sheldrake, and later Deepak Chopra were blogging about it, Sheldrake's article actually wasn't being edited that much at all! In fact, in February of this year, no one edited it at all that entire month. And all the way back to June 2012, it typically would get, like, five edits a month, six edits a month, three edits a month. Very typical for a lesser article like that.

And then all of a sudden, after Robert McLuhan's post in April, it's getting twenty-one edits, and then twenty-six. And in June, it shot up, and it accelerated from there. A large number of editors were editing the article.

What was happening, from what I can tell, is people were stepping on each others' toes, and getting in each others' way. And there were a lot of clearly, very new editors to Wikipedia jumping in, I presume, as a result of these blog posts, and trying to edit. And there was one editor in particular in June who made most of the edits in June, who had a weird random string for their name on Wikipedia. And eventually got blocked, and was accused of being a sock puppet.

And in August and September, was blocked off of Wikipedia because their edits they were making were not productive. And that was kind of the start of it; and it's gone on from there. There was another editor by the name of Tumbleman who came in around August. And he had a post on his own kind of profile page on Wikipedia that somebody dug up, that basically said he was doing an experiment in social psychology by editing the Rupert Sheldrake page, and seeing how people reacted.

Essentially, he admitted he was trolling the other editors on that page. And people accused him of it, and he deleted that from his user page. And he created all sorts of havoc on the page. That brought in another blogger by the name of Craig Weiler, who's blogged about it a few times, and that's how it got to Deepak Chopra, I think. Because Deepak Chopra mentioned Craig Weiler's blog.

But neither one, neither Tumbleman nor Craig Wheiler made that many constructive edits. In fact, I was laughing with Susan earlier because I found a blog post that Craig Wheeler made, where he referred to Sheldrake's article as “my article on Wikipedia,” which is something you never do. You never assume ownership of a Wikipedia article.

He's made one edit to the Sheldrake article, one, over the entire time. And that one edit was he deleted something, a footnote. And that's it! That's it! Yet, in his blog, if you read his blog, you would think he was making these gigantic edits that the skeptics were removing every day. He wasn't. He's been arguing with people on Wikipedia. He's only made about sixty edits, and then he finally gave up. He posted a thing on his blog that “the only way to win the Wikipedia game is to not play.”

S: Yeah. Well, good! Good riddance, right? I mean,

T: Exactly!

S: It's not like they can't get their shit together, and they're just complaining because you guys do have your shit together. You're actually making constructive, evidence-based, scholarly edits.

T: Right.

S: They just don't like what the scholarship has to say.

T: Yeah.

S: Well, let's talk about Wikipedia in general for a bit, because Wikipedia has an interesting reputation. It's all over the place. If you do a search on almost anything, any basic topic, Wikipedia comes up on the first page, if not the first hit for most things. Yet teachers, for example, usually do not allow students to reference Wikipedia for no other reason than because it's by definition a secondary source.

So it sort of has a bad reputation among scholars, yet it's emerging as – it's the closest thing to the one reservoir of human knowledge that we have. So it's kind of in this strange place in terms of its reputation as a source of information.

SG: Right. And you know, Steve, it's a great point. We hear a lot about how bad Wikipedia is, but it is the source of all knowledge. You can't beat its Google hits, the results. There's no way that anybody can write a blog, do a podcast, or anything of that sort that's gonna get the hit views that the Wikipedia page receives.

In fact, just take one, for example, homeopathy. The most popular blogger out there can do an article on homeopathy, write great evidence, cite great sources, and they're not even gonna get close to the hundred thousand views a month every month for years that Wikipedia's gonna get.

And this B.S. about not being able to cite it on scholarly, for articles and things like that. That's nice. I hear that all the time. People are always talking about, “You can't cite Wikipedia.” But everyone goes to Wikipedia.

T: Yeah.

SG: So they can flail their arms, and they can fling their arms about, and wave their hands and so on about how bad Wikipedia is, but it is where everyone is going. And there are great sources on a lot of pages that people can find when they go to familiarize themselves with a topic; to get a general overview of a historical piece, or one of our scientists, or global warming, and then follow the citations to get really good information, and then cite those.

S: Yeah.

T: That's the key that I think a lot of educational people who have a more nuanced view of Wikipedia always emphasize is, skim the article. Maybe use the article as a starting point. But one of the first things you're gonna do is go down to the bottom of the article and look at the footnotes. For a well-written article, there will be exhaustive footnotes down there. And where those footnotes lead are the sources that you're probably gonna want to really be reading after you've got sort of your CliffsNotes view from the article itself.

It varies from article to article. A lot of articles are very poor, and have just a couple of footnotes, and not very good sources. And there are other articles that have hundreds and hundreds of footnotes down there to very scholarly sources, and will really send you exactly where you need to be.

S: It does seem like this is a place where it's worthwhile for us as a community to put our efforts, because this is the show. This is the resource that people go to.

T: One of the big things that Susan has focused on, and I've focused on myself mainly just to kind of stay out of a lot of these controversies like Sheldrake and Chopra, is not necessarily diving into the controversial pseudoscience articles, but editing the articles on the other side that just document the skeptic movement.

So, writing biographies. For instance, I wrote George Hrab's biography on Wikipedia. I wrote Harriet Hall's. I wrote most of Karen Stollznow's bio. It's just a matter of finding someone like that who clearly, Harriet Hall is notable enough to be in Wikipedia, and she didn't happen to have an article, so I just sat down and started digging up references of stuff that she's written, stuff that she's done; and wrote it up, and put it in there. And it helps document skepticism for the general public.

When somebody sees an article by Harriet Hall, and they go, “Who is this Harriet Hall person?” They Google her name. There's a whole bio of her on Wikipedia.

SG: We specialize in that. We call that project “We Got Your Wiki-Back.” And we've done that time and time again in our forum. What we're trying to do is we're really trying to improve the pages of our skeptical spokespeople, and that includes the SGU as well as many other skeptical organizations and spokespeople; because what we want is when you are in the media, we know that you're gonna get Googled. We know that you're gonna get high stats because we can see that. We have a way of looking at your stats, and see how many hits come to your Wikipedia page each day.

We can look at that and we can say, “Well, so-and-so's in the news, so we gotta make sure that there are pages in really good shape; and we need to make sure that the links are going from there to scientific skepticism, to the different organizations, to the different kinds of things we have. And it needs to be done in all languages.

In fact, we've written the SGU page in - I think we just did Portuguese just recently, not so long ago. So, we have to have the pages done in English really great, and then they get translated into other languages from different people on my team.

B: Wow.

J: That is awesome! That's fantastic.

S: All right, so guys, you're gonna provide me with some links for anyone listening to the show who wants to get involved as a Wiki editor, or directly with you guys in the Guerrilla Skepticism project.

T: Yup.

S: All right guys, well, thanks for joining us tonight, and thanks for all the good work.

SG: Thank you!

T: Thank you!

Science or Fiction (1:04:21)

S: Each week I come up with three science news items or facts, two genuine and one fictitious, then I challenge my panel of skeptics to tell me which one is the fake. We have a theme this week—

E: Duh duh duh!

S: The theme is "how many?" and we have four items.

R: How many?

S: There are four items. OK. Here they are: The human body has more than 12 distinct types of sensation (without dividing taste, smell, vision, or hearing into subtypes). Item #2: There are six known moons of Pluto (five named), and 83 confirmed moons of Jupiter. Item #3: There are 11 known states of matter (not counting non-classical states and purely theoretical states). And Item #4: There are currently six people in space. So obviously, this is all about the numbers; one of those numbers is incorrect.

J: Uh, I'm not a fan of this!

S: Jay, go first.

E: (laughs)

J: OK. So, this first one. I do believe that there are other types of sensations other than the five obvious senses that we have. And I'm not dipping into "sense hunger" or any of that nonsense that L. Ron Hubbard wants us to believe. And the second one here, that there are six known moons of Pluto... oh, wow; I just—I don't even know if Pluto has any moons. That's how bad this one is. You're supposed to know stuff like that, Bob, and I'm supposed to know about yelling and bad accents.

B: (chuckles)

E: And Thanksgiving.[2]

J: Thank you. Yeah, and where was my Thanksgiving Science or Fiction, Steve? Really, really...

R: It's true.

J: You did me wrong, son. I'm not sure about the Pluto one, and I just hate having to admit to myself that I don't know more information about that. And the final one that are 11 known states of matter. Damn you! I believe there are six people in space right now, so that's the fourth one; I'm going to say that's science. Between two and three, I'm going to say that there are not 11 states of matter.

S: OK. Evan?

E: Um, for the 12 distinct types of sensation in the human body, that really doesn't make sense to me. Certainly not what we're taught in school, but that doesn't mean a damn thing these days. I'm having a problem with this one: "distinct types". I don't know that they're distinct; lot of things are connected. Six known moons of Pluto, five named, 83 confirmed moons of Jupiter? That's a lot. Always thought Jupiter was kind of in the 40s or 50s, but they're always finding new moons. I would not be surprised. Eleven known states of matter. Well, sure, I'm tending to think that that one is correct. You know, please don't ask me to name them (chuckles) because I couldn't get all eleven, I think, in under the worst of circumstances. And then this last one. There are currently six people in space. You know, what can you say about that? There either is or there isn't. And you kind of just have to take a guess with that one. So it's coming down to the six people in space or 12 distinct types of sensation. Given those two options that I've narrowed it down to, I'm going to have to say that the 12 distinct types of sensation I'll say is the fiction.

S: OK. Rebecca?

R: Oh, man. That was the one that I thought was science, 'cause... I don't know about 12, but I know that there are other senses like sense of balance I know is one that people don't ordinarily think of. And there must be more; like, I feel like psychologists are always coming up with new senses. Like, what about the sense that you're an individual? You know, there are people who have brain damage who lose certain senses about themselves and it's really freaky. So I don't know; I feel like that one could be true. Six known moons of Pluto, 83 moons of Jupiter; no idea. Honestly, I have no idea. Eleven known states of matter? I mean, I know the solid, liquid, gas, plasma. That's four. What else could there be? I don't know. Do Newtonian liquids—is that a... I don't think so. I don't—there's probably—I'm sure that there must be some other crazy states of matter that I don't know about, but... I don't know. And I have no idea how many people are in space at any one time. How do we even define space? We can't, Steve.

E: (laughs)

R: Somebody just went into space and came back just now while I was answering this question, so I don't know. I don't know; I guess I'm going to go with the states of matter one, because I feel like eleven is too many states of matter, but I'm probably way wrong.

S: OK. Bob.

B: Yeah, this is tough. These numbers are good; they're just outside of the range that I'm comfortable in. Yeah, for distinct sensations, I kind of like what Evan was saying about how twelve distinct ones definitely seems high. A lot of them are just kind of fusion of different sensations. The moons of Pluto... I wasn't aware of the sixth one, and 83 for Jupiter? Yeah, I just lost count. And that seems a little high, but not that high. The eleven known states of matter. That seems high as well; I mean, there's a bunch of them besides the obvious: plasma, Bose-Einstein condensate; there's these quasi-crystals...

R: (laughs) Were those part of the obvious?

E: Course Bob knows.

B: Quark-gluon plasma...

R: You know, the obvious ones: The Bose-Einstein crystallites.

E: He was reading a paper on that earlier today.

B: No. I said beside the obvious solid, liquid, gas.

R: Oh, OK.

B: But even for those, I remember thinking, "that's it; I've just officially lost track of how many states of matter there are." There are just all these obscure ones. Some of them are fascinating; other ones were kind of not as fascinating. But that still seems high to me. And people in space; I really don't know; six sounds reasonable. Part of me is thinking that that's such a simple little thing. There are six people in space, and that's going to be the fiction; nobody's going to pick it.

E: (laughs)

B: Jay, what did you pick?

J: I said that the eleven known states of matter.

B: Screw it. I'm going with the six people in space.

E: Right, Bob. Good for you.

S: OK. All right. So, the one that you all agree on is that there are six known moons of Pluto (five named) and 83 confirmed moons of Jupiter. You all think that is science.

E: Gosh.

B: Wait! Can I change my mind??

(laughter)

S: No.

B: I know; I know.

S: And that one is... the fiction!

E: Of course it is! Because—

R: (groans)

B: F[deleted] you, Steve!

S: Because... there are five moons of Pluto; Bob, we have not discovered a sixth.

E: Right!

R: Come on!

S: Those moons are—you should know how many moons Pluto has!

J: There are no moons of Pluto!

R: Why??

S: Charon—

E: We talked about it; Nix and... the other one.

S: Yeah, Nix and—we just talked about this![link needed]

R: Why do I ever need to know about that?

S: Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberus and Hydra.

E: Cerberus; right.

S: And Jupiter has 67 confirmed moons, not 83.

J: There's a lot of people listening to this show right now that were in the same exact shoes as I was in. Admit it, people—

E: I was right about Jupiter!

J: A lot of you should know. There's no—nobody knew that there were any moons of Jupiter. There were no moons of Jupiter before the recording of this program.

S: Jupiter? You mean Pluto.

J: Whatever!

E: Same deal.

S: Jupiter has 67 moons. All right. Let's go back over the other ones in order. The human body has more than 12 distinct types of sensation (without dividing taste, smell, vision, or hearing). That is science. I had to say "more than 12" because there's just no way to give one number. It depends on how you divide them or count them. I said "not dividing taste" because do you count bitter, salt and sweet as three sensations or one?

R: No. What are you, crazy?

S: Is color and black-and-white vision could be more than one. Every smell; how many different types of receptors do we have for smell? So I said, "just forget those; we'll keep those as just one type of sensation". But in addition to sight, smell, sound and taste, we have temperature, pain, Propioception, soft touch, pressure, vibration, vestibular sensation, itch and stretch. Like, you know when your bladder's full or if your bowel is distended.

B: Isn't itch just a form of pain?

S: That's thirteen—nope; there's a distinct receptor for it. That's thirteen; I got over 12, so I just said "more than 12". If there's more, whatever.

E: (laughs)

J: I knew it; I was right. Thank you.

E: Bastard.

S: Yeah, they actually discovered that there's—and they're distinct; they have distinct receptors, pathways—

J: Steve! I got one that you did think of: Detect fart.

S: Detect fart?

J: No, because you know they're different—

R: I believe that's pressure.

S: That's a combination of stretch and odor.

J: You know—there's a difference. You know whether you have to go to the bathroom or you have to fart. Or else we'd all be shitting our pants!

R: Well, hopefully you do. Sometimes people—

S: We'll call that the Jay Principle.

B: Not always.

J: No, I've named it "Detect Fart". Thank you.

S: (chuckles) Isn't that a Scientology power?

B: (chuckles) Yeah, right.

S: All right. There are eleven known states of matter (not counting non-classical states and purely theoretical states). So, I had to throw that caveat in there because there's all sorts of possible states of matter and I'm sure somebody could come in and say, "no, there's only eleven—there's only ten" or there's twelve or whatever. But here are the eleven. I tried to... You gotta draw the line somewhere between how much confirmation's enough to say we know that it exists.

B: Right.

S: But here's are the eleven I thought were above the board: Solid, liquid, gas, plasma—you all know about that—superfluid, Bose-Einstein condensate, fermionic condensate, Rydberg molecule, photonic matter, degenerate matter and quark-gluon plasma.

B: What about a quasi-crystal?

S: Those are non-classical states.

E: What about dark matter?

S: Dark matter's purely theoretical.

E: Uggghhh. What? Wait a minute! What do you mean, "purely theoretical"?

S: We don't know what it is. It's just theorized that it must exist.

E: But we know it exists!

S: There was like, ten other ones that probably, that theoretically should exist; we have no idea what it is. I didn't count those.

B: That's awesome. Read those again!

S: But the list could be a lot more; I mean, there's a lot more things potentially on the list.

E: Bob's getting excited.

R: Go Google it and read it yourself.

S: Solid, liquid, gas, plasma, superfluid, Bose-Einstein condensate, fermionic condensate, Rydberg molecule, photonic matter, which we talked about recently; degenerate matter, like in a neutron star and quark-gluon plasma. Quark-gluon plasma's on the fence about because—

B: Why?!

S: Because how confirmed is it? We've definitely detected it in particle accelerators, but it's not 100%, 100% confirmed. I thought it was above the bar.

B: Oh, come on. Yeah, it is.

R: I think my cat is a new state of matter, because he is soft and squishy; I can touch him, but he also seems—so that's like a solid, but he also seems to fill any space, like a gas. So like a very tiny box or a very large box; he can fill it perfectly.

J: And Rebecca, that's another sense: Detect cat.

R: Yes.

S: And, there are currently six people in space. They are: Oleg Kotov, Mike Hopkins, and Sergey Ryazanskiy; they've all been in space for 70 days. Rick Mastracchio, Mikhail Tyurin and Koichi Wakata have been in space for 28 days.

E: Hey, Koichi. He listens to the show.

J: So how many people are in space right now?

S: There's two Americans, three Russians and one Japanese.

B: Hey, I heard Koichi went home, so I think I win.

S: What do you mean? How could he have gone home?

R: He was homesick.

B: He was tired of it.

R: Had his parents pick him up.

E: No, no, he just did what Sandra Bullock did in Gravity.

S: There's a website called, "howmanypeopleareinspacerightnow.com".

R: Really?

(laughter)

B: Oh, awesome! Awesome!

S: Yup.

B: That's great.

E: What is it, just one big number six on the screen? (laughs)

S: (laughs) Yes, exactly! There's a picture of the Earth; there's a big number six on the screen. And then below that are the names. But yes, that's it!

R: Wow.

J: That is awesome.

B: What's the highest that number's ever been, I wonder?

S: I don't know.

E: Oh, gosh.

B: I should know.

R: Is there a website, "whatsthemostpeoplewhohaveeverbeeninspace.com"?

S: (laughs) We need to make one.

B: Steve!

S: Yeah?

B: Did you say, "Rydberg atom"?

S: Molecule.

B: How did they—so they classify that as a separate state of matter?

S: Rydberg molecule. They did; yeah.

B: That's interesting; OK. 'Cause isn't that where the molecule is—the electron is so far away that it actually exhibits classical and quantum characteristics?

S: I believe so; yes. I could read the description for you.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:17:18)

'The real advantage which truth has, consists in this, that when an opinion is true, it may be extinguished once, twice, or many times, but in the course of ages there will generally be found persons to rediscover it, until some one of its reappearances falls on a time when from favourable circumstances it escapes persecution until it has made such head as to withstand all subsequent attempts to suppress it.'-John Stuart Mill

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References

|