SGU Episode 898: Difference between revisions

| Line 594: | Line 594: | ||

=== It's OK to Ask for Help <small>(12:06)</small> === | === It's OK to Ask for Help <small>(12:06)</small> === | ||

* [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/well/family/asking-for-help.html Go Ahead, Ask for Help. People Are Happy to Give It.]<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/well/family/asking-for-help.html NYT: Go Ahead, Ask for Help. People Are Happy to Give It.]</ref> | * [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/well/family/asking-for-help.html Go Ahead, Ask for Help. People Are Happy to Give It.]<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/well/family/asking-for-help.html NYT: Go Ahead, Ask for Help. People Are Happy to Give It.]</ref> | ||

[12:06.160 --> 12:08.520] Kara, is it okay to ask for help when you need it? | |||

[12:08.520 --> 12:09.920] Is it okay? | |||

[12:09.920 --> 12:13.400] Not only is it okay, it's great. | |||

[12:13.400 --> 12:19.480] Let's dive into a cool study that was recently published in Psychological Science. | |||

[12:19.480 --> 12:23.680] This study has a lot of moving parts so I'm not going to get into all of them but I have | |||

[12:23.680 --> 12:29.520] to say just kind of at the top that I'm loving the thoroughness and I'm loving the clarity | |||

[12:29.520 --> 12:32.320] of the writing of this research article. | |||

[12:32.320 --> 12:37.040] I feel like it's a great example of good psychological science. | |||

[12:37.040 --> 12:39.440] It's based on a really deep literature review. | |||

[12:39.440 --> 12:44.120] A lot of people that we know and love like Dunning are cited who have co-written with | |||

[12:44.120 --> 12:45.480] some of the authors. | |||

[12:45.480 --> 12:56.720] This study basically is asking the question, why do people struggle to ask for help? | |||

[12:56.720 --> 13:01.960] When people do ask for help, what is the outcome usually? | |||

[13:01.960 --> 13:08.800] They did six, I think it was six or was it eight, I think it was six different individual | |||

[13:08.800 --> 13:12.000] experiments within this larger study. | |||

[13:12.000 --> 13:18.000] Their total and the number of people overall that were involved, that participated in the | |||

[13:18.000 --> 13:21.780] study was like over 2,000. | |||

[13:21.780 --> 13:25.180] They kind of looked at it from multiple perspectives. | |||

[13:25.180 --> 13:30.340] They said, first we're going to ask people to imagine a scenario and tell us what they | |||

[13:30.340 --> 13:34.640] think they would do or what they think the other person would feel or think. | |||

[13:34.640 --> 13:39.200] Then we're going to ask them about experiences that they've actually had, like think back | |||

[13:39.200 --> 13:43.220] to a time when you asked for help or when somebody asked you for help and then answer | |||

[13:43.220 --> 13:44.400] all these questions. | |||

[13:44.400 --> 13:50.280] Then they actually did a more real world kind of ecological study where they said, okay, | |||

[13:50.280 --> 13:52.920] we're going to put a scenario in place. | |||

[13:52.920 --> 13:59.120] Basically this scenario was in a public park, they asked people to basically go up to somebody | |||

[13:59.120 --> 14:02.700] else and be like, hey, do you mind taking a picture for me? | |||

[14:02.700 --> 14:10.200] They did a bunch of different really clean study designs where they took a portion of | |||

[14:10.200 --> 14:14.280] the people and had them be the askers and a portion of the people and have them be the | |||

[14:14.280 --> 14:17.920] non-askers and then a portion of the people and have them ask with a prompt, without a | |||

[14:17.920 --> 14:18.920] prompt. | |||

[14:18.920 --> 14:22.920] The study designs are pretty clean but they're kind of complex. | |||

[14:22.920 --> 14:26.760] What do you guys think, I mean obviously you can't answer based on every single study, | |||

[14:26.760 --> 14:31.360] but the main sort of takeaway of this was? | |||

[14:31.360 --> 14:34.040] Asking for help is good and people are willing to give the help. | |||

[14:34.040 --> 14:35.040] People like getting help. | |||

[14:35.040 --> 14:36.040] Right. | |||

[14:36.040 --> 14:37.040] Yeah. | |||

[14:37.040 --> 14:40.440] So not only do people more often than not, and not even more often than not, like almost | |||

[14:40.440 --> 14:46.200] all the time, especially in these low hanging fruit scenarios, do the thing that's asked | |||

[14:46.200 --> 14:50.200] of them, but they actually feel good about it after. | |||

[14:50.200 --> 14:54.240] They feel better having given help. | |||

[14:54.240 --> 14:58.980] And so what they wanted to look at were some of these kind of cognitive biases basically. | |||

[14:58.980 --> 15:04.560] They asked themselves, why are people so hesitant to ask for help? | |||

[15:04.560 --> 15:13.120] And they believe it's because people miscalibrate their expectations about other people's prosociality, | |||

[15:13.120 --> 15:17.640] that there's sort of a Western ideal that says people are only looking out for their | |||

[15:17.640 --> 15:21.600] own interest and they'd rather not help anybody and only help themselves. | |||

[15:21.600 --> 15:28.200] They also talk about something called compliance motivation. | |||

[15:28.200 --> 15:34.160] So they think that people are, when they actually do help you out, it's less because they want | |||

[15:34.160 --> 15:36.400] to because they're prosocial. | |||

[15:36.400 --> 15:41.100] And it's more literally because they feel like they have to, like they feel a pull to | |||

[15:41.100 --> 15:43.560] comply with a request. | |||

[15:43.560 --> 15:49.000] But it turns out that in these different studies where either they're looking at a real world | |||

[15:49.000 --> 15:54.920] example, they're asking people for imagined examples, the helpers more often than not | |||

[15:54.920 --> 15:57.360] want to help and say that they feel good about helping. | |||

[15:57.360 --> 16:01.760] But the people who need the help more often than not judge the helpers to not want to | |||

[16:01.760 --> 16:06.120] help them and worry that the helpers won't want to help them. | |||

[16:06.120 --> 16:11.200] So this is another example of kind of, do you guys remember last week, I think it was, | |||

[16:11.200 --> 16:15.400] when I talked about a study where people were trying to calibrate how much they should talk | |||

[16:15.400 --> 16:16.400] to be likable? | |||

[16:16.400 --> 16:17.400] Yeah. | |||

[16:17.400 --> 16:18.400] Yeah, so yeah. | |||

[16:18.400 --> 16:20.120] And they were, again, miscalibrating. | |||

[16:20.120 --> 16:22.000] They were saying, I shouldn't talk that much. | |||

[16:22.000 --> 16:23.240] They'll like me more if I talk less. | |||

[16:23.240 --> 16:26.360] But it turns out if you talk more, people actually like you more. | |||

[16:26.360 --> 16:31.480] And so it's another one of those examples of a cognitive bias getting in the way of | |||

[16:31.480 --> 16:37.080] us engaging in social behavior and actually kind of shooting ourselves in the foot because | |||

[16:37.080 --> 16:42.580] we fear an outcome that is basically the opposite of the outcome that we'll get. | |||

[16:42.580 --> 16:46.800] If we ask for help, we'll more than likely get it, and more than likely, the person who | |||

[16:46.800 --> 16:50.280] helped us will feel good about having helped us, and it's really a win-win. | |||

[16:50.280 --> 16:52.040] Of course, they caveated at the end. | |||

[16:52.040 --> 16:53.480] We're talking about low-hanging fruit. | |||

[16:53.480 --> 16:58.120] We're not talking about massive power differentials, you know, where one person, where there's | |||

[16:58.120 --> 17:00.000] coercion and things like that. | |||

[17:00.000 --> 17:05.040] But given some of those caveats to the side, basically an outcome of every single design | |||

[17:05.040 --> 17:07.600] that they did in the study was people want to help. | |||

[17:07.600 --> 17:09.660] And they want to help because it makes them feel good. | |||

[17:09.660 --> 17:13.240] So maybe the next time you need help, if you ask, you shall receive. | |||

[17:13.240 --> 17:15.400] Yeah, also, it works both ways, too. | |||

[17:15.400 --> 17:20.520] People often don't offer help because they are afraid that they don't understand the | |||

[17:20.520 --> 17:26.560] situation and they're basically afraid of committing a social faux pas. | |||

[17:26.560 --> 17:32.560] And so they end up not offering help, even in a situation when they probably should, | |||

[17:32.560 --> 17:33.560] you know, because the fear... | |||

[17:33.560 --> 17:34.560] Like a good Samaritan? | |||

[17:34.560 --> 17:38.840] Well, because people want to help and they want to offer to help, but they're more afraid | |||

[17:38.840 --> 17:41.400] of doing something socially awkward, and so they don't. | |||

[17:41.400 --> 17:47.040] So if you just don't worry about that and just offer to help, have a much lower threshold | |||

[17:47.040 --> 17:49.120] for offering, it's like it's no big deal. | |||

[17:49.120 --> 17:53.400] If it's like, oh, I'm fine, okay, just checking, you know, but people will not do it. | |||

[17:53.400 --> 17:58.080] I was once walking down the street and there was a guy on the sidewalk who couldn't get | |||

[17:58.080 --> 17:59.080] up. | |||

[17:59.080 --> 18:00.640] He clearly could not get up on his own, right? | |||

[18:00.640 --> 18:04.600] And there are people walking by and other people sort of like checking him out, but | |||

[18:04.600 --> 18:06.600] nobody was saying anything or offering to help. | |||

[18:06.600 --> 18:08.560] So I just, hey, you need a hand? | |||

[18:08.560 --> 18:09.560] And he did. | |||

[18:09.560 --> 18:13.080] And then like three or four people right next to him were like, oh, let me help you, you | |||

[18:13.080 --> 18:14.160] know what I mean? | |||

[18:14.160 --> 18:18.320] But it was just, again, it's not that they weren't bad people, they just were paralyzed | |||

[18:18.320 --> 18:21.200] by fear of social faux pas. | |||

[18:21.200 --> 18:24.720] So it's kind of, it's the reverse of, I guess, of what you're saying, you know, where people | |||

[18:24.720 --> 18:27.760] might not ask for help because they're afraid that it's not socially not the right thing | |||

[18:27.760 --> 18:28.760] to do. | |||

[18:28.760 --> 18:29.760] But it is. | |||

[18:29.760 --> 18:30.760] Give help, ask for help. | |||

[18:30.760 --> 18:31.760] It's all good. | |||

[18:31.760 --> 18:32.760] Everybody likes it. | |||

[18:32.760 --> 18:34.720] Just don't let your social fears get in the way. | |||

[18:34.720 --> 18:35.880] Don't let your social fears get in the way. | |||

[18:35.880 --> 18:41.360] And also there are ways to buffer if you are scared that you're like putting somebody out, | |||

[18:41.360 --> 18:44.160] is there are different like strategies that you can use. | |||

[18:44.160 --> 18:45.840] You can give people outs. | |||

[18:45.840 --> 18:50.200] You know, if you really do need help, but you also really are worried that you're going | |||

[18:50.200 --> 18:52.880] to be putting somebody out by asking for help. | |||

[18:52.880 --> 18:58.620] You can say things like, I'd really appreciate your help in this situation, but I also understand | |||

[18:58.620 --> 19:02.120] that it may be too much for you and don't worry, I'll still get it taken care of. | |||

[19:02.120 --> 19:08.360] Like there are ways to buffer and to negotiate the sociality of that so that you don't feel | |||

[19:08.360 --> 19:10.200] like you're being coercive. | |||

[19:10.200 --> 19:14.560] And so, yeah, it's like you see it all the time. | |||

[19:14.560 --> 19:16.920] People who get stuff in life ask for it. | |||

[19:16.920 --> 19:22.400] Yeah, or you could, you could do, or you could do with my, what my Italian mother does and | |||

[19:22.400 --> 19:24.280] say, don't worry about me. | |||

[19:24.280 --> 19:25.280] I'll be fine. | |||

[19:25.280 --> 19:28.080] I don't need anything. | |||

[19:28.080 --> 19:29.080] The passive guilt. | |||

[19:29.080 --> 19:30.080] They are. | |||

[19:30.080 --> 19:31.080] They're wonderful at that. | |||

[19:31.080 --> 19:34.800] Don't forget guys, don't forget. | |||

[19:34.800 --> 19:41.480] If you help somebody, they owe you someday. | |||

[19:41.480 --> 19:44.080] You might do a favor for me, you know? | |||

[19:44.080 --> 19:45.080] That's right. | |||

[19:45.080 --> 19:49.600] One of those, one of those things that my dad like drilled into my head that I like | |||

[19:49.600 --> 19:53.000] always hear in my head all the time was he would always say, you don't ask, you don't | |||

[19:53.000 --> 19:54.000] get. | |||

[19:54.000 --> 19:57.280] So like I literally hear that in my head all the time when I'm in scenarios where I want | |||

[19:57.280 --> 20:03.240] to ask for something and I totally do get that way sometimes where I'm like, yeah. | |||

=== Bitcoin and Fedimints <small>(20:03)</small> === | === Bitcoin and Fedimints <small>(20:03)</small> === | ||

Revision as of 11:55, 28 October 2022

| This transcript is not finished. Please help us finish it! Add a Transcribing template to the top of this transcript before you start so that we don't duplicate your efforts. |

Template:Editing required (w/links) You can use this outline to help structure the transcription. Click "Edit" above to begin.

| SGU Episode 898 |

|---|

| September 24th 2022 |

|

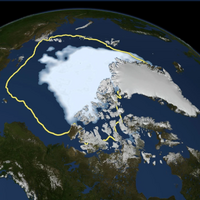

2012 Arctic sea ice minimum. Outline shows average minimum 1979-2010.[1] |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

DA: David Almeda (sp?), SGU Patron |

| Quote of the Week |

In the field of thinking, the whole history of science – from geocentrism to the Copernican revolution, from the false absolutes of Aristotle's physics to the relativity of Galileo's principle of inertia and to Einstein's theory of relativity – shows that it has taken centuries to liberate us from the systematic errors, from the illusions caused by the immediate point of view as opposed to "decentered" systematic thinking. |

– Jean Piaget, Swiss psychologist |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction, Guest Rogue

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

[00:12.880 --> 00:17.560] Today is Tuesday, September 20th, 2022, and this is your host, Stephen Novella.

[00:17.560 --> 00:18.960] Joining me this week are Bob Novella.

[00:18.960 --> 00:19.960] Hey, everybody.

[00:19.960 --> 00:20.960] Kara Santamaria.

[00:20.960 --> 00:21.960] Howdy.

[00:21.960 --> 00:22.960] Jay Novella.

[00:22.960 --> 00:23.960] Hey, guys.

[00:23.960 --> 00:24.960] Evan Bernstein.

[00:24.960 --> 00:26.760] Good evening, everyone.

[00:26.760 --> 00:30.400] And we have a guest rogue this week, David Almeida.

[00:30.400 --> 00:32.120] David, welcome to the Skeptics' Guide.

[00:32.120 --> 00:33.120] Hi, guys.

[00:33.120 --> 00:34.120] Thank you for having me.

[00:34.120 --> 00:40.440] So, David, you are a patron of the SGU, and you've been a loyal supporter for a while,

[00:40.440 --> 00:45.200] so we invited you on the show to join us and have some fun.

[00:45.200 --> 00:46.200] Tell us what you do.

[00:46.200 --> 00:47.840] Give us a little bit about your background.

[00:47.840 --> 00:48.840] I'm an electrician.

[00:48.840 --> 00:52.640] That doesn't sound very exciting relative to what you guys are all doing.

[00:52.640 --> 00:55.080] No, electricians are cool, man.

[00:55.080 --> 00:56.080] Yeah, they're shocking.

[00:56.080 --> 00:58.120] Oh, it starts.

[00:58.120 --> 01:05.640] I actually heard about your show kind of because of work, because when I was starting out as

[01:05.640 --> 01:09.920] an apprentice, pretty much all the work I did was really boring and repetitive, and

[01:09.920 --> 01:13.520] so I was kind of losing my mind a little bit.

[01:13.520 --> 01:17.080] And a friend of mine was at my house helping me work on the house, and he was playing your

[01:17.080 --> 01:20.400] guys' podcast, and I had no idea what a podcast even was.

[01:20.400 --> 01:22.200] This was like 2012, I think.

[01:22.200 --> 01:24.400] I thought he was like listening to NPR or something.

[01:24.400 --> 01:26.320] You were late to the game.

[01:26.320 --> 01:27.320] Yeah, I know.

[01:27.320 --> 01:28.320] I know.

[01:28.320 --> 01:32.320] And so anyways, he was listening to your show, and I asked him what it was, and he told me,

[01:32.320 --> 01:35.400] and then I ended up going back and listening to your whole back catalog while I was doing

[01:35.400 --> 01:41.320] horrible, very repetitive work, and it got me through that for the first couple years

[01:41.320 --> 01:42.320] of my apprenticeship.

[01:42.320 --> 01:43.320] Yeah, we hear that a lot.

[01:43.320 --> 01:49.520] It's good for when you're exercising, doing mind-numbing repetitive tasks, riding a bike

[01:49.520 --> 01:50.520] or whatever.

[01:50.520 --> 01:51.520] It's good.

[01:51.520 --> 01:53.840] You're not just going to sit there staring off into space listening to the SGU.

[01:53.840 --> 01:58.520] I guess some people might do that, but it's always good for when you're doing something

[01:58.520 --> 01:59.520] else.

[01:59.520 --> 02:00.520] Well, great.

[02:00.520 --> 02:01.520] Thanks for joining us on the show.

[02:01.520 --> 02:02.520] It should be a lot of fun.

News Items

S:

B:

C:

J:

E:

(laughs) (laughter) (applause) [inaudible]

2022 Ig Nobels (2:08)

[02:02.520 --> 02:05.640] You're going to have a news item to talk about a little bit later, but first we're just going

[02:05.640 --> 02:07.960] to dive right into some news items.

[02:07.960 --> 02:12.760] Jay, you're going to start us off by talking about this year's Ig Nobel Prizes.

[02:12.760 --> 02:14.160] Yeah, this was interesting.

[02:14.160 --> 02:22.840] This year, I didn't find anything about people getting razzed so much as I found stuff that

[02:22.840 --> 02:26.520] was basically legitimate, just weird, if you know what I mean.

[02:26.520 --> 02:28.200] Yeah, but that's kind of the Ig Nobles.

[02:28.200 --> 02:29.200] They're legit, but weird.

[02:29.200 --> 02:32.880] They're not fake science or bad science.

[02:32.880 --> 02:37.880] The Ig Nobel Prize is an honor about achievements that first make people laugh and then make

[02:37.880 --> 02:39.720] them think.

[02:39.720 --> 02:44.720] That's kind of their tagline, and it was started in 1991.

[02:44.720 --> 02:47.600] Here's a list of the 2022 winners.

[02:47.600 --> 02:48.600] Check this one out.

[02:48.600 --> 02:53.520] The first one here, the Art History Prize, they call it a multidisciplinary approach

[02:53.520 --> 02:57.600] to ritual enema scenes on ancient Maya pottery.

[02:57.600 --> 03:01.960] Whoa, I want to see those.

[03:01.960 --> 03:04.560] Talk about an insane premise.

[03:04.560 --> 03:11.680] Back in the 6-900 CE timeframe, the Mayans depicted people getting enemas on their pottery,

[03:11.680 --> 03:13.640] which that's crazy.

[03:13.640 --> 03:18.520] This is because they administered enemas back then for medicinal purposes.

[03:18.520 --> 03:20.200] So it was part of their culture.

[03:20.200 --> 03:24.200] And the researchers think it's likely that the Mayans also gave enemas that had drugs

[03:24.200 --> 03:28.000] in them to make people get high during rituals, which is-

[03:28.000 --> 03:29.000] That works, by the way.

[03:29.000 --> 03:30.000] Yeah.

[03:30.000 --> 03:33.000] So one of the lead researchers tried it.

[03:33.000 --> 03:39.960] He gave himself an alcohol enema situation, and they were giving him breathalyzer, and

[03:39.960 --> 03:43.340] lo and behold, he absorbed alcohol through his rectum.

[03:43.340 --> 03:46.120] He didn't need to do that to know that that happens.

[03:46.120 --> 03:47.120] This is science.

[03:47.120 --> 03:48.120] We already know that that happens.

[03:48.120 --> 03:49.120] What's the problem, Kara?

[03:49.120 --> 03:50.120] Science?

[03:50.120 --> 03:51.120] Hello?

[03:51.120 --> 03:52.120] Lit review.

[03:52.120 --> 03:53.120] Lit review.

[03:53.120 --> 04:01.160] The guy also tested DMT, but apparently the dose was probably not high enough for him

[04:01.160 --> 04:03.280] to feel anything because he didn't feel anything.

[04:03.280 --> 04:04.840] So I think that's pretty interesting.

[04:04.840 --> 04:09.760] I mean, that's very, very provocative, just to think that the Mayans, I didn't know they

[04:09.760 --> 04:11.160] did that, and then it was like a thing.

[04:11.160 --> 04:13.480] I was like, whatever.

[04:13.480 --> 04:16.080] Next one, Applied Cardiology Prize.

[04:16.080 --> 04:18.940] This one I find to be really cool.

[04:18.940 --> 04:24.700] So the researchers, they were seeking and finding evidence that when new romantic partners

[04:24.700 --> 04:29.880] meet for the first time and feel attracted to each other, their heart rates synchronize.

[04:29.880 --> 04:31.840] That was the premise of their research.

[04:31.840 --> 04:35.640] So the researchers wanted to find out if there is something physiological behind the gut

[04:35.640 --> 04:42.240] feeling that people can and do feel when they have met the quote unquote right person.

[04:42.240 --> 04:44.560] I don't know about you guys, but I've felt this.

[04:44.560 --> 04:49.440] I felt an inexplicable physiological thing.

[04:49.440 --> 04:53.440] I just didn't realize that something profound was happening.

[04:53.440 --> 04:55.960] So let me give you a quick idea of what they did.

[04:55.960 --> 04:58.080] They had 140 test subjects.

[04:58.080 --> 05:03.060] They monitored test subjects as they met other test subjects one on one.

[05:03.060 --> 05:09.280] If the pair got a gut feeling about the other person, the researchers predicted that they

[05:09.280 --> 05:15.660] would have motor movements, you know, act certain types of activity with their eyes,

[05:15.660 --> 05:18.440] heart rate, skin conductance.

[05:18.440 --> 05:22.020] These types of things would synchronize or they would pair each other or mirror each

[05:22.020 --> 05:23.020] other.

[05:23.020 --> 05:27.820] So 17 percent of the test subjects had what they considered to be successful pairing with

[05:27.820 --> 05:28.820] another subject.

[05:28.820 --> 05:33.760] And they found that couples heart rates and skin conductance correlated to a mutual attraction

[05:33.760 --> 05:35.060] with each other.

[05:35.060 --> 05:41.680] So there is some type of thing happening physiologically when two people, you know, get that feeling

[05:41.680 --> 05:44.520] when they're, you know, there's an initial attraction.

[05:44.520 --> 05:50.040] And it doesn't surprise me because, you know, as mammals, attraction is, you know, it's

[05:50.040 --> 05:51.480] a huge thing.

[05:51.480 --> 05:55.800] It's really it's not only important, but it, you know, your body is reacting to it.

[05:55.800 --> 06:00.180] There are things that happen when you feel that your body is is changing in a way.

[06:00.180 --> 06:01.180] Very cool.

[06:01.180 --> 06:04.960] The next one, I think a lot of people will get a kick out of the it's the literature

[06:04.960 --> 06:11.400] prize and they are analyzing what makes legal documents unnecessarily difficult to understand.

[06:11.400 --> 06:14.280] The basic idea here was there's two camps.

[06:14.280 --> 06:21.040] There's a camp that thinks that legal documents need to be as complicated as they are because

[06:21.040 --> 06:26.180] there's technical concepts and they need to be precise and they use they use this type

[06:26.180 --> 06:28.720] of language to help get that precision.

[06:28.720 --> 06:33.880] And there are other experts that think that laws are actually built upon, you know, mundane

[06:33.880 --> 06:38.360] concepts like cause consent and having best interests.

[06:38.360 --> 06:42.100] And what the researchers wanted to do was they wanted to test the two positions against

[06:42.100 --> 06:43.100] each other.

[06:43.100 --> 06:47.600] And essentially what they found, which is which is not going to surprise anyone, that

[06:47.600 --> 06:53.840] legal documents are at their core, essentially difficult to understand, which is what they

[06:53.840 --> 06:55.320] basically started with that premise.

[06:55.320 --> 07:00.640] But they proved it and they found out exactly what parts of the of the actual legal documents

[07:00.640 --> 07:02.080] were difficult to understand.

[07:02.080 --> 07:07.380] And they called it something called center embedding, which is when lawyers use legal

[07:07.380 --> 07:11.920] jargon within what they call convoluted syntax.

[07:11.920 --> 07:16.420] So in essence, I think what they're saying here is that that legal documents are difficult

[07:16.420 --> 07:21.800] essentially by design, that it's deliberate, which I find interesting and frustrating.

[07:21.800 --> 07:26.680] If you've ever had to read any type of legal documentation, it's kind of annoying how difficult

[07:26.680 --> 07:27.680] it is.

[07:27.680 --> 07:30.860] You have to reread it over and over and over again and look things up and really like sink

[07:30.860 --> 07:32.000] into it to understand.

[07:32.000 --> 07:34.320] So I understand why they did the research.

[07:34.320 --> 07:37.500] I just don't see what the benefit is to the result of their research.

[07:37.500 --> 07:38.720] Maybe they have to iterate it.

[07:38.720 --> 07:41.920] The center embedding thing is actually pretty interesting.

[07:41.920 --> 07:48.120] I saw an example of it and it's like not like it's not what I thought it was going to be.

[07:48.120 --> 07:52.760] It gives an example of like a sentence like a man loves a woman and then a man that a

[07:52.760 --> 07:57.880] woman that a child knows loves a man that a woman that a child that a bird saw is giving

[07:57.880 --> 08:03.840] these examples of like how they do the legal jargon with all those like with all those

[08:03.840 --> 08:08.520] little like phrases within phrases.

[08:08.520 --> 08:12.120] And it's like grammatically correct, but it's like impossible to follow once you have like

[08:12.120 --> 08:13.440] more than one of those.

[08:13.440 --> 08:16.480] The longest one they had here was a man that a woman that a child that a bird that I heard

[08:16.480 --> 08:18.680] saw knows loves.

[08:18.680 --> 08:23.720] I don't know how that actually makes grammatical sense, but apparently it does.

[08:23.720 --> 08:26.960] It makes no sense to me even though I read it like five times in my head.

[08:26.960 --> 08:29.000] I don't know what that sentence means.

[08:29.000 --> 08:33.500] Have you guys seen I just started watching that show Maid.

[08:33.500 --> 08:35.000] Have you guys seen that show on Netflix?

[08:35.000 --> 08:36.000] It's so good.

[08:36.000 --> 08:37.840] Oh, highly recommend.

[08:37.840 --> 08:41.660] But they do this funny thing where like she has to go to a court hearing and they kind

[08:41.660 --> 08:45.600] of show what she hears instead of what is being said.

[08:45.600 --> 08:51.680] And so she's at this custody hearing and the judge is talking to one of the prosecutors

[08:51.680 --> 08:56.620] and like mid-sentence they start going, and then legal, legal, legal, legal, so that you

[08:56.620 --> 08:57.720] can legal, legal.

[08:57.720 --> 08:59.520] I'll legal, legal after you legal.

[08:59.520 --> 09:02.520] And she like looked so confused because it's all she hears.

[09:02.520 --> 09:06.680] And they do it on the forms too when she looks at the forms like the words move and they

[09:06.680 --> 09:08.960] start to just say like legal, legal, legal, legal.

[09:08.960 --> 09:13.360] It's a great representation of exactly what you're talking about.

[09:13.360 --> 09:14.360] Totally.

[09:14.360 --> 09:17.360] The Charlie Brown teacher.

[09:17.360 --> 09:18.360] Charlie Brown.

[09:18.360 --> 09:19.360] Yeah.

[09:19.360 --> 09:20.360] Totally.

[09:20.360 --> 09:22.080] Let me get through a few more really quick.

[09:22.080 --> 09:26.720] There was a biology prize where they studied whether and how constipation affects the mating

[09:26.720 --> 09:28.360] prospects of scorpions.

[09:28.360 --> 09:36.540] There was a medical prize for showing that when patients undergo some form of toxic chemotherapy,

[09:36.540 --> 09:41.720] they suffer fewer harmful side effects when ice cream replaces ice chips.

[09:41.720 --> 09:42.720] Okay.

[09:42.720 --> 09:43.720] Reasonable to me.

[09:43.720 --> 09:44.720] Reasonable.

[09:44.720 --> 09:45.720] Unactionable.

[09:45.720 --> 09:46.720] Yep, it is.

[09:46.720 --> 09:47.720] And it's legit.

[09:47.720 --> 09:48.720] It is actually legit.

[09:48.720 --> 09:53.080] The ice cream, giving chemo patients ice cream helped them a lot more deal with side effects

[09:53.080 --> 09:55.280] than ice chips.

[09:55.280 --> 09:59.300] Their engineering prize, they're trying to discover the most efficient way for people

[09:59.300 --> 10:04.400] to use their fingers when turning a knob, doorknob.

[10:04.400 --> 10:09.920] That's you know, so they study people turning doorknobs and figured it out.

[10:09.920 --> 10:14.040] Works for trying to understand how ducklings manage to swim in formation.

[10:14.040 --> 10:20.520] Now this is cool because we know that fish and birds have very few rules of interaction

[10:20.520 --> 10:26.640] in order to do profound feats of being able to stay in these giant groups.

[10:26.640 --> 10:27.640] They could swim near each other.

[10:27.640 --> 10:31.600] They can fly near each other and they don't really need to have a complicated algorithm

[10:31.600 --> 10:32.600] happening.

[10:32.600 --> 10:34.560] They just have to follow a few simple rules and it works.

[10:34.560 --> 10:36.240] And apparently ducks can do it too.

[10:36.240 --> 10:40.720] There was a peace prize and this one is for developing an algorithm to help gossipers

[10:40.720 --> 10:43.800] decide when to tell the truth and when to lie.

[10:43.800 --> 10:44.800] Very important.

[10:44.800 --> 10:45.800] Right?

[10:45.800 --> 10:47.200] That's just wacky as hell.

[10:47.200 --> 10:52.740] The economics prize for explaining mathematically why success most often goes not to the most

[10:52.740 --> 10:55.460] talented people but instead to the luckiest.

[10:55.460 --> 10:56.460] That one was interesting.

[10:56.460 --> 10:57.840] I recommend you read that.

[10:57.840 --> 11:04.400] And then this last one here is safety engineering prize for developing a moose crash test dummy.

[11:04.400 --> 11:05.400] That's smart actually.

[11:05.400 --> 11:06.400] Yeah.

[11:06.400 --> 11:09.480] So you know lots of people hit these animals with their cars.

[11:09.480 --> 11:12.800] I heard you hesitate because you didn't know if you're supposed to say moose or mooses.

[11:12.800 --> 11:13.800] Meeses.

[11:13.800 --> 11:14.800] I don't know.

[11:14.800 --> 11:15.800] You were like hit these animals.

[11:15.800 --> 11:16.800] Animals.

[11:16.800 --> 11:17.800] Yeah.

[11:17.800 --> 11:18.800] I'm not going to.

[11:18.800 --> 11:19.800] What the heck?

[11:19.800 --> 11:20.800] What's the plural of moose?

[11:20.800 --> 11:21.800] Isn't it moose?

[11:21.800 --> 11:22.800] Yeah.

[11:22.800 --> 11:25.720] I think the plural of moose is moose.

[11:25.720 --> 11:27.640] I just add a K in when I don't know what to do.

[11:27.640 --> 11:29.520] Have I told you the story about the mongoose?

[11:29.520 --> 11:30.520] No.

[11:30.520 --> 11:31.520] What?

[11:31.520 --> 11:32.520] I heard.

[11:32.520 --> 11:33.520] I learned this.

[11:33.520 --> 11:43.760] I heard this in my film class where a director needed two mongoose for a scene and he couldn't

[11:43.760 --> 11:46.640] figure out what the plural of mongoose was.

[11:46.640 --> 11:49.780] You know the mongooses, mongies, whatever, he couldn't figure it out.

[11:49.780 --> 11:56.120] So he wrote in his message to the person who had to do this, I need you to get me one mongoose

[11:56.120 --> 11:59.600] and while you're at it get me another one.

[11:59.600 --> 12:04.160] Yeah, technically solves that problem.

[12:04.160 --> 12:05.160] All right.

[12:05.160 --> 12:06.160] Thanks Jay.

It's OK to Ask for Help (12:06)

[12:06.160 --> 12:08.520] Kara, is it okay to ask for help when you need it?

[12:08.520 --> 12:09.920] Is it okay?

[12:09.920 --> 12:13.400] Not only is it okay, it's great.

[12:13.400 --> 12:19.480] Let's dive into a cool study that was recently published in Psychological Science.

[12:19.480 --> 12:23.680] This study has a lot of moving parts so I'm not going to get into all of them but I have

[12:23.680 --> 12:29.520] to say just kind of at the top that I'm loving the thoroughness and I'm loving the clarity

[12:29.520 --> 12:32.320] of the writing of this research article.

[12:32.320 --> 12:37.040] I feel like it's a great example of good psychological science.

[12:37.040 --> 12:39.440] It's based on a really deep literature review.

[12:39.440 --> 12:44.120] A lot of people that we know and love like Dunning are cited who have co-written with

[12:44.120 --> 12:45.480] some of the authors.

[12:45.480 --> 12:56.720] This study basically is asking the question, why do people struggle to ask for help?

[12:56.720 --> 13:01.960] When people do ask for help, what is the outcome usually?

[13:01.960 --> 13:08.800] They did six, I think it was six or was it eight, I think it was six different individual

[13:08.800 --> 13:12.000] experiments within this larger study.

[13:12.000 --> 13:18.000] Their total and the number of people overall that were involved, that participated in the

[13:18.000 --> 13:21.780] study was like over 2,000.

[13:21.780 --> 13:25.180] They kind of looked at it from multiple perspectives.

[13:25.180 --> 13:30.340] They said, first we're going to ask people to imagine a scenario and tell us what they

[13:30.340 --> 13:34.640] think they would do or what they think the other person would feel or think.

[13:34.640 --> 13:39.200] Then we're going to ask them about experiences that they've actually had, like think back

[13:39.200 --> 13:43.220] to a time when you asked for help or when somebody asked you for help and then answer

[13:43.220 --> 13:44.400] all these questions.

[13:44.400 --> 13:50.280] Then they actually did a more real world kind of ecological study where they said, okay,

[13:50.280 --> 13:52.920] we're going to put a scenario in place.

[13:52.920 --> 13:59.120] Basically this scenario was in a public park, they asked people to basically go up to somebody

[13:59.120 --> 14:02.700] else and be like, hey, do you mind taking a picture for me?

[14:02.700 --> 14:10.200] They did a bunch of different really clean study designs where they took a portion of

[14:10.200 --> 14:14.280] the people and had them be the askers and a portion of the people and have them be the

[14:14.280 --> 14:17.920] non-askers and then a portion of the people and have them ask with a prompt, without a

[14:17.920 --> 14:18.920] prompt.

[14:18.920 --> 14:22.920] The study designs are pretty clean but they're kind of complex.

[14:22.920 --> 14:26.760] What do you guys think, I mean obviously you can't answer based on every single study,

[14:26.760 --> 14:31.360] but the main sort of takeaway of this was?

[14:31.360 --> 14:34.040] Asking for help is good and people are willing to give the help.

[14:34.040 --> 14:35.040] People like getting help.

[14:35.040 --> 14:36.040] Right.

[14:36.040 --> 14:37.040] Yeah.

[14:37.040 --> 14:40.440] So not only do people more often than not, and not even more often than not, like almost

[14:40.440 --> 14:46.200] all the time, especially in these low hanging fruit scenarios, do the thing that's asked

[14:46.200 --> 14:50.200] of them, but they actually feel good about it after.

[14:50.200 --> 14:54.240] They feel better having given help.

[14:54.240 --> 14:58.980] And so what they wanted to look at were some of these kind of cognitive biases basically.

[14:58.980 --> 15:04.560] They asked themselves, why are people so hesitant to ask for help?

[15:04.560 --> 15:13.120] And they believe it's because people miscalibrate their expectations about other people's prosociality,

[15:13.120 --> 15:17.640] that there's sort of a Western ideal that says people are only looking out for their

[15:17.640 --> 15:21.600] own interest and they'd rather not help anybody and only help themselves.

[15:21.600 --> 15:28.200] They also talk about something called compliance motivation.

[15:28.200 --> 15:34.160] So they think that people are, when they actually do help you out, it's less because they want

[15:34.160 --> 15:36.400] to because they're prosocial.

[15:36.400 --> 15:41.100] And it's more literally because they feel like they have to, like they feel a pull to

[15:41.100 --> 15:43.560] comply with a request.

[15:43.560 --> 15:49.000] But it turns out that in these different studies where either they're looking at a real world

[15:49.000 --> 15:54.920] example, they're asking people for imagined examples, the helpers more often than not

[15:54.920 --> 15:57.360] want to help and say that they feel good about helping.

[15:57.360 --> 16:01.760] But the people who need the help more often than not judge the helpers to not want to

[16:01.760 --> 16:06.120] help them and worry that the helpers won't want to help them.

[16:06.120 --> 16:11.200] So this is another example of kind of, do you guys remember last week, I think it was,

[16:11.200 --> 16:15.400] when I talked about a study where people were trying to calibrate how much they should talk

[16:15.400 --> 16:16.400] to be likable?

[16:16.400 --> 16:17.400] Yeah.

[16:17.400 --> 16:18.400] Yeah, so yeah.

[16:18.400 --> 16:20.120] And they were, again, miscalibrating.

[16:20.120 --> 16:22.000] They were saying, I shouldn't talk that much.

[16:22.000 --> 16:23.240] They'll like me more if I talk less.

[16:23.240 --> 16:26.360] But it turns out if you talk more, people actually like you more.

[16:26.360 --> 16:31.480] And so it's another one of those examples of a cognitive bias getting in the way of

[16:31.480 --> 16:37.080] us engaging in social behavior and actually kind of shooting ourselves in the foot because

[16:37.080 --> 16:42.580] we fear an outcome that is basically the opposite of the outcome that we'll get.

[16:42.580 --> 16:46.800] If we ask for help, we'll more than likely get it, and more than likely, the person who

[16:46.800 --> 16:50.280] helped us will feel good about having helped us, and it's really a win-win.

[16:50.280 --> 16:52.040] Of course, they caveated at the end.

[16:52.040 --> 16:53.480] We're talking about low-hanging fruit.

[16:53.480 --> 16:58.120] We're not talking about massive power differentials, you know, where one person, where there's

[16:58.120 --> 17:00.000] coercion and things like that.

[17:00.000 --> 17:05.040] But given some of those caveats to the side, basically an outcome of every single design

[17:05.040 --> 17:07.600] that they did in the study was people want to help.

[17:07.600 --> 17:09.660] And they want to help because it makes them feel good.

[17:09.660 --> 17:13.240] So maybe the next time you need help, if you ask, you shall receive.

[17:13.240 --> 17:15.400] Yeah, also, it works both ways, too.

[17:15.400 --> 17:20.520] People often don't offer help because they are afraid that they don't understand the

[17:20.520 --> 17:26.560] situation and they're basically afraid of committing a social faux pas.

[17:26.560 --> 17:32.560] And so they end up not offering help, even in a situation when they probably should,

[17:32.560 --> 17:33.560] you know, because the fear...

[17:33.560 --> 17:34.560] Like a good Samaritan?

[17:34.560 --> 17:38.840] Well, because people want to help and they want to offer to help, but they're more afraid

[17:38.840 --> 17:41.400] of doing something socially awkward, and so they don't.

[17:41.400 --> 17:47.040] So if you just don't worry about that and just offer to help, have a much lower threshold

[17:47.040 --> 17:49.120] for offering, it's like it's no big deal.

[17:49.120 --> 17:53.400] If it's like, oh, I'm fine, okay, just checking, you know, but people will not do it.

[17:53.400 --> 17:58.080] I was once walking down the street and there was a guy on the sidewalk who couldn't get

[17:58.080 --> 17:59.080] up.

[17:59.080 --> 18:00.640] He clearly could not get up on his own, right?

[18:00.640 --> 18:04.600] And there are people walking by and other people sort of like checking him out, but

[18:04.600 --> 18:06.600] nobody was saying anything or offering to help.

[18:06.600 --> 18:08.560] So I just, hey, you need a hand?

[18:08.560 --> 18:09.560] And he did.

[18:09.560 --> 18:13.080] And then like three or four people right next to him were like, oh, let me help you, you

[18:13.080 --> 18:14.160] know what I mean?

[18:14.160 --> 18:18.320] But it was just, again, it's not that they weren't bad people, they just were paralyzed

[18:18.320 --> 18:21.200] by fear of social faux pas.

[18:21.200 --> 18:24.720] So it's kind of, it's the reverse of, I guess, of what you're saying, you know, where people

[18:24.720 --> 18:27.760] might not ask for help because they're afraid that it's not socially not the right thing

[18:27.760 --> 18:28.760] to do.

[18:28.760 --> 18:29.760] But it is.

[18:29.760 --> 18:30.760] Give help, ask for help.

[18:30.760 --> 18:31.760] It's all good.

[18:31.760 --> 18:32.760] Everybody likes it.

[18:32.760 --> 18:34.720] Just don't let your social fears get in the way.

[18:34.720 --> 18:35.880] Don't let your social fears get in the way.

[18:35.880 --> 18:41.360] And also there are ways to buffer if you are scared that you're like putting somebody out,

[18:41.360 --> 18:44.160] is there are different like strategies that you can use.

[18:44.160 --> 18:45.840] You can give people outs.

[18:45.840 --> 18:50.200] You know, if you really do need help, but you also really are worried that you're going

[18:50.200 --> 18:52.880] to be putting somebody out by asking for help.

[18:52.880 --> 18:58.620] You can say things like, I'd really appreciate your help in this situation, but I also understand

[18:58.620 --> 19:02.120] that it may be too much for you and don't worry, I'll still get it taken care of.

[19:02.120 --> 19:08.360] Like there are ways to buffer and to negotiate the sociality of that so that you don't feel

[19:08.360 --> 19:10.200] like you're being coercive.

[19:10.200 --> 19:14.560] And so, yeah, it's like you see it all the time.

[19:14.560 --> 19:16.920] People who get stuff in life ask for it.

[19:16.920 --> 19:22.400] Yeah, or you could, you could do, or you could do with my, what my Italian mother does and

[19:22.400 --> 19:24.280] say, don't worry about me.

[19:24.280 --> 19:25.280] I'll be fine.

[19:25.280 --> 19:28.080] I don't need anything.

[19:28.080 --> 19:29.080] The passive guilt.

[19:29.080 --> 19:30.080] They are.

[19:30.080 --> 19:31.080] They're wonderful at that.

[19:31.080 --> 19:34.800] Don't forget guys, don't forget.

[19:34.800 --> 19:41.480] If you help somebody, they owe you someday.

[19:41.480 --> 19:44.080] You might do a favor for me, you know?

[19:44.080 --> 19:45.080] That's right.

[19:45.080 --> 19:49.600] One of those, one of those things that my dad like drilled into my head that I like

[19:49.600 --> 19:53.000] always hear in my head all the time was he would always say, you don't ask, you don't

[19:53.000 --> 19:54.000] get.

[19:54.000 --> 19:57.280] So like I literally hear that in my head all the time when I'm in scenarios where I want

[19:57.280 --> 20:03.240] to ask for something and I totally do get that way sometimes where I'm like, yeah.

Bitcoin and Fedimints (20:03)

Multivitamins for Memory (28:17)

- [link_URL Effects of cocoa extract and a multivitamin on cognitive function: A randomized clinical trial][5]

Refreezing the Poles (42:07)

Neuro Emotional Technique (55:50)

- The Neuro Emotional Technique Is a Bizarre Hybrid of Chiropractic, Acupuncture, and Applied Kinesiology[7]

Who's That Noisy? (1:07:17)

J: ... I did. This Noisy has appeared on the show before.[link needed]

New Noisy (1:12:05)

[gibberish song with trumpet and percussion beat]

J: So if you think you know what this week's Noisy is ...

Announcements (1:13:06)

Questions/Emails/Corrections/Follow-ups (1:16:39)

Followup #1: Chess Cheating

Science or Fiction (1:23:43)

Theme: Global Warming

Item #1: A survey of 48 coastal cities finds that they are sinking at an average rate of 16.2 mm per year, with the fastest at 43 mm per year. (For reference, average global sea level rise is 3.7 mm per year.)[8]

Item #2: A recent study estimates the total social cost of releasing carbon into the atmosphere at $185 per tonne, which is triple the current US government estimate. (For reference, the world emits >34 billion tonnes of CO2 each year.)[9]

Item #3: The latest climate models indicate that even with rapid decarbonization it is too late to prevent eventual warming >1.5 C.[10]

| Answer | Item |

|---|---|

| Fiction | Too late to prevent >1.5 °C |

| Science | Carbon release estimate |

| Science | Cities are sinking |

| Host | Result |

|---|---|

| Steve | win |

| Rogue | Guess |

|---|---|

David | Cities are sinking |

Jay | Too late to prevent >1.5 °C |

Bob | Too late to prevent >1.5 °C |

Evan | Too late to prevent >1.5 °C |

Cara | Too late to prevent >1.5 °C |

Voice-over: It's time for Science or Fiction.

David's Response

Jay's Response

Bob's Response

Evan's Response

Cara's Response

Steve Explains Item #2

Steve Explains Item #1

Steve Explains Item #3

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:41:09)

In the field of thinking, the whole history of science – from geocentrism to the Copernican revolution, from the false absolutes of Aristotle's physics to the relativity of Galileo's principle of inertia and to Einstein's theory of relativity – shows that it has taken centuries to liberate us from the systematic errors, from the illusions caused by the immediate point of view as opposed to "decentered" systematic thinking.

– Jean Piaget (1896-1980), Swiss psychologist

Signoff

S: —and until next week, this is your Skeptics' Guide to the Universe.

S: Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information, visit us at theskepticsguide.org. Send your questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. And, if you would like to support the show and all the work that we do, go to patreon.com/SkepticsGuide and consider becoming a patron and becoming part of the SGU community. Our listeners and supporters are what make SGU possible.

Today I Learned

- Fact/Description, possibly with an article reference[11]

- Fact/Description

- Fact/Description

Notes

References

- ↑ MPR: Arctic ice shrinks to all-time low; half 1980 size

- ↑ Ars Technica: Here are the winners of the 2022 Ig Nobel Prizes

- ↑ NYT: Go Ahead, Ask for Help. People Are Happy to Give It.

- ↑ Bitcoin Magazine: Can fedimints help bitcoin scale to the world?

- ↑ [url_from_news_item_show_notes Alzheimer's Association: Effects of cocoa extract and a multivitamin on cognitive function: A randomized clinical trial]

- ↑ Institute of Physics: Refreezing Earth's poles feasible and cheap, new study finds

- ↑ McGill: The Neuro Emotional Technique Is a Bizarre Hybrid of Chiropractic, Acupuncture, and Applied Kinesiology

- ↑ NTU Singapore: Rapid land sinking leaves global cities vulnerable to rising seas

- ↑ Nature: Comprehensive Evidence Implies a Higher Social Cost of CO2

- ↑ One Earth: Achieving the Paris Climate Goals in the COVID-19 era

- ↑ [url_for_TIL publication: title]

Vocabulary

|