SGU Episode 266: Difference between revisions

Jason koziol (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Jason koziol (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

S: And, I have to say I watched your talk today and, I love the material by the way, I love the talk. The kind of stuff you deal with really is, in my opinion, at the absolute core of skepticism. Which is the knowledge about how our brains function, how they filter information, and deal with the world around us. So, give us a little flavor of your talk today and tell us what are those things that you've learned in your career that really...that you feel are most relevant to what we do as skeptics. | S: And, I have to say I watched your talk today and, I love the material by the way, I love the talk. The kind of stuff you deal with really is, in my opinion, at the absolute core of skepticism. Which is the knowledge about how our brains function, how they filter information, and deal with the world around us. So, give us a little flavor of your talk today and tell us what are those things that you've learned in your career that really...that you feel are most relevant to what we do as skeptics. | ||

BH: Okay | BH: Okay so, really the talk was trying to draw people's attention to the basic function of a brain, which is to interpret the world and make sense of it, and to build models if you like. Allows you to make predictions, figure out why things are the way they are. It's like a causal inference mechanism. And, it's usually pretty good. It's done us well for all these millions of years. But it has a few built in, uh, flaws. And, sometimes it makes errors, and those errors, I think, could underpin a lot of supernatural beliefs. | ||

S: Mm- | S: Mm-hm. | ||

BH: The assumption that there are hidden forces or dimensions, | BH: The assumption that there are hidden forces or dimensions, or things operating which can't be explained by science. | ||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

BH: Okay? I think one of the critical points I was making in the demonstrations throughout the talk was showing how people shouldn't even trust their own senses. Because, you know the phrase, "seeing is believing"? Well, I hopefully demonstrated today that that's not the case. | |||

S: Right. | |||

B: Believing is seeing in many cases. | |||

BH: Indeed. Yeah, so that's an example where your models of the world really color the way you interpret the world. The late Richard Gregory was a great friend of mine he said this 50 years ago that, you need these models of the world to interpret it. And that of course, sort of, constrains the sorts of things that you pay attention to. | |||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

BH: So believing very much you're seeing its the way that you go out and you sample information to fit. | |||

S: Yeah. | |||

BH: And part of that process occasionally produces these explanations... | |||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

BH: ...which don't really hold up under the scrutiny of evidence. | |||

S: Right. Now you said one word during your talk that caught my attention which I thought was for me a core concept. You didn't focus on it but I knew what you were saying and you said that the...our perception of the world is a ''constructive'' process. | |||

BH: Mm-hm, mm-hm. | |||

S: That's a deceptively deep little concept you threw in there in the middle of your talk it's not something that we passively... | |||

BH: Yeah | |||

S: ...are perceiving, we're constructing it with tons of assumptions. | |||

BH: Yeah | |||

S: Can you elaborate that a little bit? | |||

BH: You don't have any privileged, direct access to reality. Your brain is always extrapolating on the basis of information it's receiving, and then it's constructing that into a framework. To try and make the best fitting model to what you think you're seeing. | |||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

BH: And so one of the very simple visual illusions I talked about are these ones where you think you see a geometric shape which is basically an illusory subjective contour. Now the interesting thing about that it's a very simple demonstration everyone sees the illusory shape but what they may not appreciate is that if you go into the brain we can find cells which are firing as if that object really was there. | |||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

BH: So it doesn't make the distinction between the fact of reality and the illusion because the brain, if it's come up with that solution, it says, well, there really should be a shape there, so fire as if it really is there. So that was the basic point, that all of our phenomenological experience is really extrapolated, is really constructed... | |||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

BH: ...from the information. And of course your models that you apply to interpret information will allow you to imagine all sorts of things, so... | |||

S: Mm-hm. | |||

== Science or Fiction <small>()</small> == | == Science or Fiction <small>()</small> == | ||

Revision as of 07:33, 6 December 2014

| This episode needs: transcription, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 266 |

|---|

| August 19th 2010 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

BH: Bruce Hood |

| Quote of the Week |

'You know that chemistry has an impact on your daily life, but the extent of that impact can be mind-boggling. Consider just the beginning of a typical day from a chemical point of view. Molecules align in the liquid crystal display of your clock, electrons flow through its circuitry to create a rousing sound, and you throw off a thermal insulator of manufactured polymer. You jump in the shower, to emulsify fatty substances on your skin and hair with chemically treated water and formulated detergents. You adorn yourself in an array of processed chemicals - pleasant-smelling pigmented materials suspended in cosmetic gels, dyed polymeric fibers, synthetic footware, and metal-alloyed jewelry. Today, breakfast is a bowl of nutrient-enriched, spoilage-retarded cereal and milk, a piece of fertilizer-grown, pesticide-treated fruit, and a cup of a hot, aqueous solution of neurally stimulating alkaloid. Ready to leave, you collect some books - processed cellulose and plastic, electrically printed with light-and-oxygen-resistant inks - hop in your hydrocarbon-fuelled metal-vinyl-ceramic vehicle, electrically ignite a synchronized series of controlled, gaseous explosions, and you're off to class!' |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

News Items ()

Banning Wi-Fi ()

Psychic Finds Wrong Body ()

Kurzweil and Brain Complexity ()

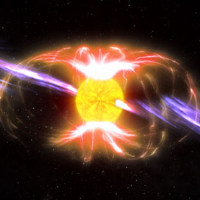

Magnetars and Black Holes ()

Who's That Noisy ()

- Answer to last week - spiney lobster

Interview with Bruce Hood ()

- Author of SuperSense

S: We're sitting here at TAM 8 with Bruce Hood, author of "Super Sense", Bruce, welcome back to the Skeptic's Guide.

Bruce Hood: Hi.

S: And, I have to say I watched your talk today and, I love the material by the way, I love the talk. The kind of stuff you deal with really is, in my opinion, at the absolute core of skepticism. Which is the knowledge about how our brains function, how they filter information, and deal with the world around us. So, give us a little flavor of your talk today and tell us what are those things that you've learned in your career that really...that you feel are most relevant to what we do as skeptics.

BH: Okay so, really the talk was trying to draw people's attention to the basic function of a brain, which is to interpret the world and make sense of it, and to build models if you like. Allows you to make predictions, figure out why things are the way they are. It's like a causal inference mechanism. And, it's usually pretty good. It's done us well for all these millions of years. But it has a few built in, uh, flaws. And, sometimes it makes errors, and those errors, I think, could underpin a lot of supernatural beliefs.

S: Mm-hm.

BH: The assumption that there are hidden forces or dimensions, or things operating which can't be explained by science.

S: Mm-hm.

BH: Okay? I think one of the critical points I was making in the demonstrations throughout the talk was showing how people shouldn't even trust their own senses. Because, you know the phrase, "seeing is believing"? Well, I hopefully demonstrated today that that's not the case.

S: Right.

B: Believing is seeing in many cases.

BH: Indeed. Yeah, so that's an example where your models of the world really color the way you interpret the world. The late Richard Gregory was a great friend of mine he said this 50 years ago that, you need these models of the world to interpret it. And that of course, sort of, constrains the sorts of things that you pay attention to.

S: Mm-hm.

BH: So believing very much you're seeing its the way that you go out and you sample information to fit.

S: Yeah.

BH: And part of that process occasionally produces these explanations...

S: Mm-hm.

BH: ...which don't really hold up under the scrutiny of evidence.

S: Right. Now you said one word during your talk that caught my attention which I thought was for me a core concept. You didn't focus on it but I knew what you were saying and you said that the...our perception of the world is a constructive process.

BH: Mm-hm, mm-hm.

S: That's a deceptively deep little concept you threw in there in the middle of your talk it's not something that we passively...

BH: Yeah

S: ...are perceiving, we're constructing it with tons of assumptions.

BH: Yeah

S: Can you elaborate that a little bit?

BH: You don't have any privileged, direct access to reality. Your brain is always extrapolating on the basis of information it's receiving, and then it's constructing that into a framework. To try and make the best fitting model to what you think you're seeing.

S: Mm-hm.

BH: And so one of the very simple visual illusions I talked about are these ones where you think you see a geometric shape which is basically an illusory subjective contour. Now the interesting thing about that it's a very simple demonstration everyone sees the illusory shape but what they may not appreciate is that if you go into the brain we can find cells which are firing as if that object really was there.

S: Mm-hm.

BH: So it doesn't make the distinction between the fact of reality and the illusion because the brain, if it's come up with that solution, it says, well, there really should be a shape there, so fire as if it really is there. So that was the basic point, that all of our phenomenological experience is really extrapolated, is really constructed...

S: Mm-hm.

BH: ...from the information. And of course your models that you apply to interpret information will allow you to imagine all sorts of things, so...

S: Mm-hm.

Science or Fiction ()

Item #1: A new analysis confirms that the so-called mitochondrial eve lived about 200,000 years ago. Item #2: New research indicates that for adults internet access at home is significantly associated with a decreased probability of being involved in a romantic relationship. Item #3: New images of the Moon's surface indicate that the Moon is shrinking - by about 100 meters in the recent past.

Quote of the Week ()

'You know that chemistry has an impact on your daily life, but the extent of that impact can be mind-boggling. Consider just the beginning of a typical day from a chemical point of view. Molecules align in the liquid crystal display of your clock, electrons flow through its circuitry to create a rousing sound, and you throw off a thermal insulator of manufactured polymer. You jump in the shower, to emulsify fatty substances on your skin and hair with chemically treated water and formulated detergents. You adorn yourself in an array of processed chemicals - pleasant-smelling pigmented materials suspended in cosmetic gels, dyed polymeric fibers, synthetic footware, and metal-alloyed jewelry. Today, breakfast is a bowl of nutrient-enriched, spoilage-retarded cereal and milk, a piece of fertilizer-grown, pesticide-treated fruit, and a cup of a hot, aqueous solution of neurally stimulating alkaloid. Ready to leave, you collect some books - processed cellulose and plastic, electrically printed with light-and-oxygen-resistant inks - hop in your hydrocarbon-fuelled metal-vinyl-ceramic vehicle, electrically ignite a synchronized series of controlled, gaseous explosions, and you're off to class!' Martin S. Silberberg

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by the New England Skeptical Society in association with the James Randi Educational Foundation and skepchick.org. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at www.theskepticsguide.org. For questions, suggestions, and other feedback, please use the "Contact Us" form on the website, or send an email to info@theskepticsguide.org. If you enjoyed this episode, then please help us spread the word by voting for us on Digg, or leaving us a review on iTunes. You can find links to these sites and others through our homepage. 'Theorem' is produced by Kineto, and is used with permission.

References

|