SGU Episode 972: Difference between revisions

Hearmepurr (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Hearmepurr (talk | contribs) news item done |

||

| Line 259: | Line 259: | ||

|redirect_title = <!-- optional...use _Redirect_title_(NNN) to prompt a redirect page to be created; hide the redirect title inside this markup text when redirect is created --> | |redirect_title = <!-- optional...use _Redirect_title_(NNN) to prompt a redirect page to be created; hide the redirect title inside this markup text when redirect is created --> | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''S:''' Have you guys heard all the hubbub about the pesticides in like oatmeal and oat products and Cheerios? | |||

...micrograms per kilogram (µg/kg)... | '''J:''' Yes. | ||

'''E:''' Oh, I read something about that recently. | |||

'''C:''' I thought I read something about like- | |||

'''E:''' Yeah, terrible chemicals. | |||

'''C:''' -lead or iron, not pesticides. Am I wrong? | |||

'''B:''' The study doesn't bear that out, does it? | |||

'''S:''' So there was a study published by the Environmental Working Group, right? Who is, in my opinion, kind of a... They're an advocacy group, not an objective scientific group. And they tend to always sort of over call the risk of toxicity, you know? So I always like it's... That's a red flag for me if the EWG is involved. So they did a study looking at the levels of a specific pesticide called chlormequat in oat-based products in the United States and in urine samples collected from people in the United States from 2017, 2018 to 2022, and then 2023, those three time periods. Why did they do this? So chlormequat is technically a pesticide because it's an herbicide. And what it does is it reduces the growth of the long stem of certain crops, right? So they don't grow as tall. And that helps in a couple of ways. It reduces the risk that the stalk will bend over or break, and it makes it easier to harvest as well, right? Without affecting, adversely affecting the thing you're trying to harvest, right? The rest of the crop. In the United States presently, it's approved for use in ornamental plants, but not food crops. In the European Union, it's approved for use in food crops like oats. In 2018, the U.S. changed their regulations allowing for the import of grains from the EU that were grown with chlormequat. So we still don't use it in the U.S., but now we are allowing the import of food from the EU that did use it. I was interested in that out of the gate because generally speaking, the EU has stricter regulations and restrictions than the U.S. does. So this was odd that it was flipped. But anyway, so they were measuring, okay, well, is it being found in U.S. food and is it being found in the urine of people in the U.S.? So even before you do the study, the answer is, of course it is because we went from not having it in the food stream to having it in the food stream. So the result seems pretty obvious. But okay, fine. They wanted to see confirm that and see how much. And they found pretty much exactly what they were looking for. Yes, many of the products that they tested, they said all but two of 25 conventional oat-based products had detectable levels of chlormequat in it and with a range of non-detectable to 291 micrograms per kilogram. And they found concentrations in the urine of subjects as well. And that concentration increased from 2018 to 2023 because, of course, it did. And now we're importing oats from Europe that were grown using it. So they basically used this as an opportunity to advocate against the U.S. loosening up the restrictions on chlormequat, which they're considering doing, and saying if you want to avoid it, you can eat organic. You could buy organic stuff, right? So they're shilling for the organic industry and they're always about like more restrictions on anything chemical used in agriculture. So the reporting on this has been horrible because they're basically buying the Environmental Working Groups' framing of this hook, line, and sinker. For example, a headline from a CBS News report, Pesticides Linked to Reproductive Issues Found in Cheerios, Quaker Oats, and Other Oat-Based Food. And then you read the article and it's all just quoting from the Environmental Working Group and without any real context. My first question was, what? What do you guys think? When you hear this story, what's your first question? | |||

'''E:''' There are trace amounts of all kinds of things in our food. How dangerous is the amount of this? | |||

'''S:''' What's the amount? What's the dose? | |||

'''C:''' Yeah. What's the dose. | |||

'''B:''' What did they find? | |||

'''C:''' And what's the outcome of that dose? Like what should we expect from that dose? | |||

'''S:''' Exactly. So there are established safety limits. You know, the U.S. has its safety limit. The European Union has its safety limit. In the U.S., the safety limit is 0.05 milligrams per kilogram body weight per day. And in the European Food Safety Authority, it's 0.4 milligrams per kilogram per body weight per day. So you notice anything about the units so far that I've thrown out there? | |||

'''J:''' Or their kilograms, they're not- | |||

'''E:''' Grams. We're talking metric. | |||

'''S:''' So the amount they're detecting in the oats is in the micrograms per kilogram (µg/kg). | |||

'''B:''' Yeah. That's a millionth of a gram, right? | |||

'''S:''' And the safety limits are in the milligrams per kilogram. | |||

'''B:''' Thousandth of a gram. | |||

'''C:''' So that's three. Yeah. That's three decimals away. | |||

'''S:''' That's three orders of magnitude. And they say in the study that the amounts that we're detecting are several orders of magnitude below the established safety limits. Yeah. Because they are. And, of course, none of the reporting mentions this, right? I actually did a fun calculation. I calculated how many kilograms of oats you would have to eat every day in order to get up to the lower end of the limit of the safety levels the safety regulation. | |||

'''J:''' Can I guess? | |||

'''S:''' Yeah. What do you think? | |||

'''J:''' What measurement are you using? | |||

'''S:''' How many kilograms of oats would you need to eat to get enough chloroquine to exceed the lower limit of the safety levels? | |||

'''E:''' And a kilogram is, what, 2.2 pounds? | |||

'''S:''' Yeah. | |||

'''J:''' Okay. | |||

'''B:''' A centillion tons. | |||

'''J:''' I'd say 10 pounds a day. | |||

'''S:''' Ten pounds a day. | |||

'''E:''' Ten pounds. That's about, what, four kilos? | |||

'''S:''' Four kilos a day. | |||

'''E:''' 4.3 kilos. | |||

'''C:''' And you said this is for – you calculated it for what, like rolled oats? Did you also calculate it for something like oatmeal? Is it somehow concentrated? | |||

'''S:''' I used the highest level that they reported. | |||

'''C:''' No, I know what I'm saying in terms – I mean the delivery method because some people drink oat milk. I don't know if it's like – is the concentration higher or lower in something like – | |||

'''S:''' Well, let's say dry oats because I'm just giving you the levels that they detected like in Cheerios or in Quaker Oats or whatever. | |||

'''C:''' All right. So you're saying how many like – how many oats, like actual like bowls of oatmeal? | |||

'''S:''' Yeah. In kilograms. | |||

'''E:''' But in kilograms. | |||

'''C:''' In kilograms. | |||

'''E:''' 2.2 pounds. | |||

'''S:''' Because that's what they needed. | |||

'''E:''' It's at least one kilogram. Let's say 12 kilograms. 12 kilos. | |||

'''C:''' Yeah. 10 or 12. I don't know. | |||

'''S:''' 85,000 kilograms. | |||

'''E:''' Oh my gosh. It's even worse. | |||

'''C:''' OK. So it doesn't matter. | |||

'''S:''' All your questions are – | |||

'''E:''' We're in homeopathy territory for all intents and purposes. | |||

'''S:''' Exactly. | |||

'''E:''' Yeah. | |||

'''S:''' We're at homeopathic doses of chlormequat. | |||

'''E:''' Yeah, right. Avogadro here. | |||

'''S:''' Now, here's the thing. | |||

'''J:''' You have to eat that every day? | |||

'''S:''' Every day. In the study – | |||

'''E:''' Every day. | |||

'''S:''' In the study – | |||

'''E:''' For what, like three months, right? | |||

'''S:''' They say – no, it's every day. They say, now, we know that these urine levels that we're detecting probably represent ongoing exposure because chloroquine is rapidly eliminated from the body through the urine. | |||

'''E:''' There you go. Kidneys. Thank you. | |||

'''S:''' So this isn't something that built up over time. They must be consuming this every day. It's like, yeah. It's rapidly eliminated from your body through the kidneys. Think about that. That also means that you would have to eat those 85,000 kilograms of oats every single day. Right? And the moment you stop doing that, your body would clear it out of your system. I mean, it's just – | |||

'''E:''' It brings it into the implausibility category. | |||

'''S:''' That's the several orders. So again, it's several orders of magnitude. | |||

'''E:''' Impossible. | |||

'''C:''' Yeah, I'd say impossible. | |||

'''S:''' It's impossible. Obviously, it's impossible. But not only that, but when the EU and the EPA, whatever, when they establish safety limits, they're already going one or two orders of magnitude below the lowest dose that was shown to cause toxicity. Right? | |||

'''C:''' Always? | |||

'''S:''' Yeah. They take like – Yeah. They use the data, usually animal data. So at this dose, we start to see adverse health effects. So let's go one or two orders of magnitude below that, and that's where we'll set our safety limit. That's standard procedure. So then you go three orders of magnitude further below that. | |||

'''C:''' I always wondered about the politics of that for something like lead back in the day. I would have assumed they would have erred in the other direction, sadly. I'd be wrong. | |||

'''S:''' No, that's the standard procedure. Go at least an order of magnitude below where you start to see adverse effects. So no one mentioned this. Then they say – Also, the toxicity that they're talking about, like the reproductive issues, that's only in animals. Never been shown in humans. | |||

'''C:''' Yeah. | |||

'''S:''' And it's shown in animals at massive doses. Again, at these kinds of ridiculous doses, right? Of course, because that's where you set the – That's how the safety limits were set. So it's ridiculous. | |||

'''C:''' Because you can probably feed a farm animal pounds and pounds of oats, but like we don't do that. | |||

'''S:''' It's still fine. It's 80,000 kilograms, Cara. | |||

'''C:''' That's great. | |||

'''S:''' It's ridiculous. The whole thing is silly. It's silly. | |||

'''E:''' It's like a silo of oats or something, right? I mean how – | |||

'''C:''' Is there an animal that can eat that much? | |||

'''S:''' So what's the – The only thing I could see that the purpose of this whole thing is just to create a round of fear mongering in the press to lobby against the U.S. changing regulations to shill for organic food. When I wrote about it on Science Based Medicine in the comments, someone pointed out, it's also – Another thing, whether this is their purpose or not, it also accomplishes the goal of leveling the playing field between traditional or standard agriculture and organic. Because if you basically deprive agriculture of using all of the science and technology that we have available, then it narrows the benefit that the increased productivity and cost effectiveness and land use and all that, that standard agriculture has above organic agriculture. It's like you can't use GMOs. You can't benefit from GMOs because they're trying to ban it because then that narrows the gap of the advantage over organic, right? So it also creates the – Well, just eat organic just to be safe. You know, because then – Just to be safe. | |||

'''E:''' Be extra safe. | |||

'''S:''' Yeah. It's absolutely ridiculous. This is why I have a massive problem with the Environmental Working Group because they pull this kind of shit all the time. | |||

'''E:''' And the media is, of course, willing to go along on the ride. | |||

'''S:''' Yeah. They didn't want to spend – Whatever. Because this is being reported probably by people who are not science journalists and they're quoting experts, right? So they think their job is done. They didn't take the 10 minutes it would take to ask the most basic question. It's like, well, they just quote somebody from the EPA that's saying this is below safety limits, right? And then they quote somebody from Quaker Road saying we follow all regulations, which always sounds like – Even though it's true. | |||

'''C:''' Yeah, it sounds sketchy as hell. | |||

'''S:''' It sounds sketchy as hell because – Yeah, because – | |||

'''J:''' We follow all regulations. | |||

'''E:''' It's designed to meet legal scrutinies, right? Anything that can be used against them in court. | |||

'''S:''' It sounds like boilerplate denial, right? And rather than saying- | |||

'''E:''' Yeah, boiler speak. | |||

'''S:''' Yeah, we asked an independent scientist to tell us what's going on here and put it into some context for it, and they told us you'd have to eat 80,000 kilograms every day for this to be of any concern. Whatever. | |||

'''C:''' Right. Which we don't recommend doing anyway. | |||

'''S:''' – Which we don't recommend. Yeah, right. By the way, people- | |||

'''C:''' Kill you. For other reasons. | |||

'''E:''' You would die of a million other things before you died of this toxicity if you consumed that much. | |||

'''S:''' The chlormequat would be the least of your problems, yeah. | |||

'''C:''' I think you would explode, like, all of your organs. | |||

'''J:''' I'm getting gassy just talking about this. | |||

=== AI Video <small>(21:36)</small> === | === AI Video <small>(21:36)</small> === | ||

Revision as of 10:36, 15 April 2024

| This transcript is not finished. Please help us finish it! Add a Transcribing template to the top of this transcript before you start so that we don't duplicate your efforts. |

| This episode needs: transcription, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

You can use this outline to help structure the transcription. Click "Edit" above to begin.

| SGU Episode 972 |

|---|

| February 24th 2024 |

|

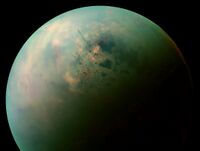

"The subsurface ocean of Titan is most likely a non-habitable environment, meaning any hope of finding life in the icy world is dead in the water." [1] |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

CS: Chris Smith, British virologist, |

| Quote of the Week |

The spirit of Plato dies hard. We have been unable to escape the philosophical tradition that what we can see and measure in the real world is merely the superficial and imperfect representation of an underlying reality. |

Stephen Jay Gould, |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction, Eclipse 2024 reminders

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, February 21st, 2024, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening folks.

S: How's everyone doing this fine day?

B: Doing good.

C: Doing all right.

E: Not too shabby.

J: All right then.

C: Did the rain finally stop?

S: Yeah, we're finally in the middle of an actual winter with cold weather and snow and everything.

C: Really?

E: Yeah.

B: Fifteen degrees Fahrenheit this morning.

C: Ooh, yikes. We had like three days of nonstop rain after we already had those two intense storms. So more mudslides, more flooding.

E: I heard a lake formed in Death Valley.

C: I heard that too.

E: That's how much rain.

B: What?

E: Yeah.

C: And it's gone already.

E: Outstanding water for several days. Yes.

C: But it's crazy how like powerful the sun is here. I went outside this morning and everything was still really wet and I just let my dog out before recording and it's like almost bone dry outside already.

S: So last, two episodes ago, we were chatting about the eclipse coming up in April. And I wanted to clarify a few things that we said during the discussion. So Evan, you said that the old eclipse glasses or solar glasses may not work, right? That they may expire after a certain amount of time.

E: Yeah. The cheapo ones.

S: So we were questioned about that. So we looked it up to get all the details. And it turns out that what you're saying is true, but it's a little outdated in that in 2015, there was a requirement in the US at least to adhere to international standards in terms of making solar glasses or eclipse glasses. And those do not automatically expire, right? So you could use them theoretically forever. However, there's a big caveat to that. And a lot of sites point this out, is that that assumes they're in good condition, right? So if you packed them away and put them away somewhere safe, yes, you can take them out again four years later or whatever and they're still good. But if you threw them in a drawer somewhere and they're like scratched or damaged in any way, do not use them. So old glasses comes with a lot of caveats. It's only if you've kept them in good condition. Because even a little scratch, that could be-

E: A pinhole could do damage.

S: Yeah. It could do significant damage.

J: Oh, wow. I mean, they're cheap. Just get new ones at this point.

S: Yeah. Why risk it? Just get new ones.

E: Better safe than sorry.

C: And you'll also know if you go outside and put them on and look up, you'll see. That's the thing about eclipse. They're so obvious.

S: Oh, yeah.

C: The sky will be black if you're wearing eclipse glasses in the middle of the day. And the only way that you'll be able to see the sun is if you know where it is and you look straight at it in the glasses.

S: Anything other than looking directly at the sun is pure blackness.

C: Yeah.

S: Right. The other thing is we were talking about when you should use the eclipse glasses and we just made a couple of general comments. But there's a lot of details there too that I was finding out. So one is that, well, of course, I don't think this needs to be said, but we're going to say it anyway. You can never, ever look directly at the sun at any time, at any part of the eclipse. The only time is during total totality. That's the only time you can look directly at the sun is during totality. However, there's one nuance to that that's interesting. At the beginning and at the end of totality, there's the so-called diamond ring effect, right? Where you get a bright rim around the sun.

C: Almost like a little lens flare.

S: Yeah. And it lasts for one to two seconds. So the question is, is it safe to look at that without your solar eclipse glasses on? And like when you say, so here I've read multiple recommendations, but most of the like official recommendations from NASA or astronomy or whatever, they say you have the eclipse glasses on when the diamond ring thing happens. When that is done, then you can take the eclipse glasses off. And then at the end of the eclipse, as soon as you see the diamond ring effect, you have to put your solar glasses back on again.

C: But that part is really, like it takes the amount of time it takes to put glasses on or take them off for that to happen. I think the thing that we have to remember is we're talking about this as if people aren't going to know the difference. It's like, have you ever looked up when the sun was in the sky? Don't look at it. It hurts.

S: Oh, yeah.

E: And that's the reason why...

S: Here's the thing Cara, so this is why there's so much discussion about like, is it safe to look at an eclipse? So you're right. If you look at the sun, it's extremely bright and it's painful. And you know, are your pupils clamped on? You squint, you look away. You can't, you'd have to really try to stare into the sun long enough to burn your retinas. But when enough of the sun is covered, it's the total brightness isn't enough to cause pain or discomfort or to close down your pupils. But that little sliver of light is still bright enough to burn your retina. So that's the most dangerous time is when your protective reflexes aren't in place, but that rim of that crescent of sun is still bright enough to burn your retina. So you're just basically burning up little crescents in your retina while you're looking at the eclipse without that protective effect.

C: I get that. But I also like, I don't know, in my experience, it's not easy to look at the sun until it's in totality. It's a concerted effort. You are still squinting into the sun if you're trying to look at it with your naked eyes, which you should never do. There's a huge difference between a partial eclipse and a total eclipse. It's massive. And so I more say that not because it's like, of course, I think that that's all really, really good advice. I also think, gosh, I hope people already know not to look at the sun with their naked eyes. I say it mostly because a lot of people are really scared of like, when will I know when it's okay? And it's like, you'll know.

S: Yeah, you'll know. It's not subtle.

C: There's a massive difference. It's not something that you have to calculate. It's not something that you have to work out on paper. It's really clear and obvious when you're in partial and when you go into totality.

S: Right. But don't take the lack of pain during partial eclipses thinking it's okay. I can look at, oh, it's not hurting. I can look at that crescent of sun. No, you can't.

C: Right. Yeah. Never look at the sun.

C: Yeah, it will still burn your eyes. It will still burn your retina.

E: Oh, my gosh. Not a good idea. Nope.

S: Yeah. And if you want to risk the one or two seconds of watching the diamond ring, that's fine. Just be careful. Just know that it's very quick. And as soon as that crescent appears, you've got to look away and put your glasses back on or whatever. If you blow the timing, as somebody pointed out, it's like if you try to, at the beginning, if you try to take your glasses off before the diamond ring effect so you see it and you get a glare from the crescent sun, that could also spoil your viewing for a while.

C: It does. Yeah. It bleaches you a little bit. That's true.

S: Yeah. You're not going to be dark adapted.

C: Yeah. Just wear your glasses the whole time. You'll know when-

S: Except in full totality.

C: Yeah. You'll know when totality happens. It will get dark. The minute it gets dark, you can take them off.

E: You will see the stars. That's how dark it will get.

C: Maybe. Depending on where you live. Probably not in LA.

E: You will see the stars.

C: Oh, wait. There is no eclipse in LA.

E: No.

C: You might not in Dallas proper see the stars. You might.

E: No. You will. I think you will. Why wouldn't you?

C: Because of the light pollution.

S: Well, the lights won't be on.

E: But will it illuminate during the day? The streetlights, they're not going to turn the streetlights on all of a sudden.

C: No, but there's a shitload of light pollution all the time. Trust me. If you can't see the stars in a nice clear night in Dallas, you're probably not going to see them in the middle of the day during an eclipse. here's a ton of light pollution.

S: That's interesting. Yeah.

B: There's one star I'm going to see, and I'll be looking at it.

C: Yeah. Well, and you are going to see stars. I mean, I'm just saying it's not going to be like the Milky Way. Don't expect during a total solar eclipse for the sky to suddenly look like Death Valley.

S: It's not going to be a dark sky viewing event.

C: Yeah. And also, there's still light all around the horizon. So like you might see a couple stars if you're in a place where it's relatively easy to see stars.

B: Oh, interesting. Yeah.

C: But it's not like the sky's-

E: Saw stars in Oregon. That's for sure.

C: Yeah. But Oregon is a pretty dark sky. Like there are parts of Oregon that are really dark. I was at least kind of out in the middle of nowhere. Were you also?

E: Yes. Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

C: Most people probably won't be for this. Some people will be along the path, but people who are going to like major metropolitan areas for it.

E: We're in a metropolitan area, I suppose. Yeah. Interesting. I don't know. I've never been in this environment, a metropolitan area during an eclipse. This will be a first.

C: I hear people cheering and stuff. It's really cool.

E: Oh, it's going to be amazing. It's going to be so good. Indescribable.

S: All right, guys. Let's go on with our news items.

News Items

Pesticides in Oats (9:07)

S: Have you guys heard all the hubbub about the pesticides in like oatmeal and oat products and Cheerios?

J: Yes.

E: Oh, I read something about that recently.

C: I thought I read something about like-

E: Yeah, terrible chemicals.

C: -lead or iron, not pesticides. Am I wrong?

B: The study doesn't bear that out, does it?

S: So there was a study published by the Environmental Working Group, right? Who is, in my opinion, kind of a... They're an advocacy group, not an objective scientific group. And they tend to always sort of over call the risk of toxicity, you know? So I always like it's... That's a red flag for me if the EWG is involved. So they did a study looking at the levels of a specific pesticide called chlormequat in oat-based products in the United States and in urine samples collected from people in the United States from 2017, 2018 to 2022, and then 2023, those three time periods. Why did they do this? So chlormequat is technically a pesticide because it's an herbicide. And what it does is it reduces the growth of the long stem of certain crops, right? So they don't grow as tall. And that helps in a couple of ways. It reduces the risk that the stalk will bend over or break, and it makes it easier to harvest as well, right? Without affecting, adversely affecting the thing you're trying to harvest, right? The rest of the crop. In the United States presently, it's approved for use in ornamental plants, but not food crops. In the European Union, it's approved for use in food crops like oats. In 2018, the U.S. changed their regulations allowing for the import of grains from the EU that were grown with chlormequat. So we still don't use it in the U.S., but now we are allowing the import of food from the EU that did use it. I was interested in that out of the gate because generally speaking, the EU has stricter regulations and restrictions than the U.S. does. So this was odd that it was flipped. But anyway, so they were measuring, okay, well, is it being found in U.S. food and is it being found in the urine of people in the U.S.? So even before you do the study, the answer is, of course it is because we went from not having it in the food stream to having it in the food stream. So the result seems pretty obvious. But okay, fine. They wanted to see confirm that and see how much. And they found pretty much exactly what they were looking for. Yes, many of the products that they tested, they said all but two of 25 conventional oat-based products had detectable levels of chlormequat in it and with a range of non-detectable to 291 micrograms per kilogram. And they found concentrations in the urine of subjects as well. And that concentration increased from 2018 to 2023 because, of course, it did. And now we're importing oats from Europe that were grown using it. So they basically used this as an opportunity to advocate against the U.S. loosening up the restrictions on chlormequat, which they're considering doing, and saying if you want to avoid it, you can eat organic. You could buy organic stuff, right? So they're shilling for the organic industry and they're always about like more restrictions on anything chemical used in agriculture. So the reporting on this has been horrible because they're basically buying the Environmental Working Groups' framing of this hook, line, and sinker. For example, a headline from a CBS News report, Pesticides Linked to Reproductive Issues Found in Cheerios, Quaker Oats, and Other Oat-Based Food. And then you read the article and it's all just quoting from the Environmental Working Group and without any real context. My first question was, what? What do you guys think? When you hear this story, what's your first question?

E: There are trace amounts of all kinds of things in our food. How dangerous is the amount of this?

S: What's the amount? What's the dose?

C: Yeah. What's the dose.

B: What did they find?

C: And what's the outcome of that dose? Like what should we expect from that dose?

S: Exactly. So there are established safety limits. You know, the U.S. has its safety limit. The European Union has its safety limit. In the U.S., the safety limit is 0.05 milligrams per kilogram body weight per day. And in the European Food Safety Authority, it's 0.4 milligrams per kilogram per body weight per day. So you notice anything about the units so far that I've thrown out there?

J: Or their kilograms, they're not-

E: Grams. We're talking metric.

S: So the amount they're detecting in the oats is in the micrograms per kilogram (µg/kg).

B: Yeah. That's a millionth of a gram, right?

S: And the safety limits are in the milligrams per kilogram.

B: Thousandth of a gram.

C: So that's three. Yeah. That's three decimals away.

S: That's three orders of magnitude. And they say in the study that the amounts that we're detecting are several orders of magnitude below the established safety limits. Yeah. Because they are. And, of course, none of the reporting mentions this, right? I actually did a fun calculation. I calculated how many kilograms of oats you would have to eat every day in order to get up to the lower end of the limit of the safety levels the safety regulation.

J: Can I guess?

S: Yeah. What do you think?

J: What measurement are you using?

S: How many kilograms of oats would you need to eat to get enough chloroquine to exceed the lower limit of the safety levels?

E: And a kilogram is, what, 2.2 pounds?

S: Yeah.

J: Okay.

B: A centillion tons.

J: I'd say 10 pounds a day.

S: Ten pounds a day.

E: Ten pounds. That's about, what, four kilos?

S: Four kilos a day.

E: 4.3 kilos.

C: And you said this is for – you calculated it for what, like rolled oats? Did you also calculate it for something like oatmeal? Is it somehow concentrated?

S: I used the highest level that they reported.

C: No, I know what I'm saying in terms – I mean the delivery method because some people drink oat milk. I don't know if it's like – is the concentration higher or lower in something like –

S: Well, let's say dry oats because I'm just giving you the levels that they detected like in Cheerios or in Quaker Oats or whatever.

C: All right. So you're saying how many like – how many oats, like actual like bowls of oatmeal?

S: Yeah. In kilograms.

E: But in kilograms.

C: In kilograms.

E: 2.2 pounds.

S: Because that's what they needed.

E: It's at least one kilogram. Let's say 12 kilograms. 12 kilos.

C: Yeah. 10 or 12. I don't know.

S: 85,000 kilograms.

E: Oh my gosh. It's even worse.

C: OK. So it doesn't matter.

S: All your questions are –

E: We're in homeopathy territory for all intents and purposes.

S: Exactly.

E: Yeah.

S: We're at homeopathic doses of chlormequat.

E: Yeah, right. Avogadro here.

S: Now, here's the thing.

J: You have to eat that every day?

S: Every day. In the study –

E: Every day.

S: In the study –

E: For what, like three months, right?

S: They say – no, it's every day. They say, now, we know that these urine levels that we're detecting probably represent ongoing exposure because chloroquine is rapidly eliminated from the body through the urine.

E: There you go. Kidneys. Thank you.

S: So this isn't something that built up over time. They must be consuming this every day. It's like, yeah. It's rapidly eliminated from your body through the kidneys. Think about that. That also means that you would have to eat those 85,000 kilograms of oats every single day. Right? And the moment you stop doing that, your body would clear it out of your system. I mean, it's just –

E: It brings it into the implausibility category.

S: That's the several orders. So again, it's several orders of magnitude.

E: Impossible.

C: Yeah, I'd say impossible.

S: It's impossible. Obviously, it's impossible. But not only that, but when the EU and the EPA, whatever, when they establish safety limits, they're already going one or two orders of magnitude below the lowest dose that was shown to cause toxicity. Right?

C: Always?

S: Yeah. They take like – Yeah. They use the data, usually animal data. So at this dose, we start to see adverse health effects. So let's go one or two orders of magnitude below that, and that's where we'll set our safety limit. That's standard procedure. So then you go three orders of magnitude further below that.

C: I always wondered about the politics of that for something like lead back in the day. I would have assumed they would have erred in the other direction, sadly. I'd be wrong.

S: No, that's the standard procedure. Go at least an order of magnitude below where you start to see adverse effects. So no one mentioned this. Then they say – Also, the toxicity that they're talking about, like the reproductive issues, that's only in animals. Never been shown in humans.

C: Yeah.

S: And it's shown in animals at massive doses. Again, at these kinds of ridiculous doses, right? Of course, because that's where you set the – That's how the safety limits were set. So it's ridiculous.

C: Because you can probably feed a farm animal pounds and pounds of oats, but like we don't do that.

S: It's still fine. It's 80,000 kilograms, Cara.

C: That's great.

S: It's ridiculous. The whole thing is silly. It's silly.

E: It's like a silo of oats or something, right? I mean how –

C: Is there an animal that can eat that much?

S: So what's the – The only thing I could see that the purpose of this whole thing is just to create a round of fear mongering in the press to lobby against the U.S. changing regulations to shill for organic food. When I wrote about it on Science Based Medicine in the comments, someone pointed out, it's also – Another thing, whether this is their purpose or not, it also accomplishes the goal of leveling the playing field between traditional or standard agriculture and organic. Because if you basically deprive agriculture of using all of the science and technology that we have available, then it narrows the benefit that the increased productivity and cost effectiveness and land use and all that, that standard agriculture has above organic agriculture. It's like you can't use GMOs. You can't benefit from GMOs because they're trying to ban it because then that narrows the gap of the advantage over organic, right? So it also creates the – Well, just eat organic just to be safe. You know, because then – Just to be safe.

E: Be extra safe.

S: Yeah. It's absolutely ridiculous. This is why I have a massive problem with the Environmental Working Group because they pull this kind of shit all the time.

E: And the media is, of course, willing to go along on the ride.

S: Yeah. They didn't want to spend – Whatever. Because this is being reported probably by people who are not science journalists and they're quoting experts, right? So they think their job is done. They didn't take the 10 minutes it would take to ask the most basic question. It's like, well, they just quote somebody from the EPA that's saying this is below safety limits, right? And then they quote somebody from Quaker Road saying we follow all regulations, which always sounds like – Even though it's true.

C: Yeah, it sounds sketchy as hell.

S: It sounds sketchy as hell because – Yeah, because –

J: We follow all regulations.

E: It's designed to meet legal scrutinies, right? Anything that can be used against them in court.

S: It sounds like boilerplate denial, right? And rather than saying-

E: Yeah, boiler speak.

S: Yeah, we asked an independent scientist to tell us what's going on here and put it into some context for it, and they told us you'd have to eat 80,000 kilograms every day for this to be of any concern. Whatever.

C: Right. Which we don't recommend doing anyway.

S: – Which we don't recommend. Yeah, right. By the way, people-

C: Kill you. For other reasons.

E: You would die of a million other things before you died of this toxicity if you consumed that much.

S: The chlormequat would be the least of your problems, yeah.

C: I think you would explode, like, all of your organs.

J: I'm getting gassy just talking about this.

AI Video (21:36)

University Rankings Flawed (36:56)

Mewing and Looksmaxxing (47:15)

Titan Uninhabitable (58:39)

B:...unladen African elephant...

Who's That Noisy? (1:11:51)

New Noisy (1:16:39)

[Wisps, clicks, and bell-like dings]

J:... this week's Noisy...

Announcements (1:17:16)

J: _jay_mentions_Live_1000th_show_from_Chicago_

Interview with Chris Smith (1:18:57)

- From Wikipedia: Chris Smith - "the Naked Scientist" - is a British consultant virologist and a lecturer based at Cambridge University. He is also a science radio broadcaster and writer, and presents The Naked Scientists, a programme which he founded in 2001, for BBC Radio and other networks internationally, as well as 5 live Science on BBC Radio 5 Live.

- The Naked Scientists: Meet the team

Science or Fiction (1:49:58)

Theme: Eclipses

Item #1: All four gas giants in our solar system experience total solar eclipses, from the perspective of their gassy surfaces.[7]

Item #2: On average, any spot on Earth will see a total solar eclipse every 375 years.[8]

Item #3: The first recorded accurate prediction of a solar eclipse was in 2300 BC, by Chinese astronomer, Li Shu, for Emporer Zhong Kang.[9]

| Answer | Item |

|---|---|

| Fiction | First recorded prediction |

| Science | Gas giants' total eclipses |

| Science | Total eclipse every 375y |

| Host | Result |

|---|---|

| Steve | win |

| Rogue | Guess |

|---|---|

Jay | Total eclipse every 375y |

Cara | First recorded prediction |

Bob | First recorded prediction |

Evan | First recorded prediction |

Voice-over: It's time for Science or Fiction.

Jay's Response

Cara's Response

Bob's Response

Evan's Response

Steve Explains Item #1

Steve Explains Item #2

Steve Explains Item #3

Skeptical Quote of the Week (2:02:53)

The spirit of Plato dies hard. We have been unable to escape the philosophical tradition that what we can see and measure in the real world is merely the superficial and imperfect representation of an underlying reality.

– Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002), American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, from his book The Mismeasure of Man, page 269

Signoff

S: —and until next week, this is your Skeptics' Guide to the Universe.

S: Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information, visit us at theskepticsguide.org. Send your questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. And, if you would like to support the show and all the work that we do, go to patreon.com/SkepticsGuide and consider becoming a patron and becoming part of the SGU community. Our listeners and supporters are what make SGU possible.

Today I Learned

- Fact/Description, possibly with an article reference[10]

- Fact/Description

- Fact/Description

References

- ↑ Phys.org: Saturn's largest moon most likely uninhabitable

- ↑ Science-Based Medicine: Pesticide in Oat Products – Should You Worry?

- ↑ Open AI: Sora is an AI model that can create realistic and imaginative scenes from text instructions.

- ↑ The Conversation: University rankings are unscientific and bad for education: experts point out the flaws

- ↑ The Guardian: From bone smashing to chin extensions: how ‘looksmaxxing’ is reshaping young men’s faces

- ↑ Phys.org (Astrobiology): Saturn's largest moon most likely uninhabitable

- ↑ Exploratorium: Our Home, Earth

- ↑ Astronomy.com: How often do solar eclipses occur?

- ↑ Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai: Eclipses in ancient cultures

- ↑ [url_for_TIL publication: title]

|