SGU Episode 889: Difference between revisions

Hearmepurr (talk | contribs) (skeptical quote completed) |

Hearmepurr (talk | contribs) (signoff completed) |

||

| Line 1,412: | Line 1,412: | ||

<!-- ** if the signoff includes announcements or any additional conversation, it would be appropriate to include a timestamp for when this part starts | <!-- ** if the signoff includes announcements or any additional conversation, it would be appropriate to include a timestamp for when this part starts | ||

--> | --> | ||

'''S:''' —and until next week, this is your {{SGU}}. <!-- typically this is the last thing before the Outro --> | '''S:''' —and until next week, this is your {{SGU}}. <!-- typically this is the last thing before the Outro --> | ||

| Line 1,444: | Line 1,418: | ||

--> | --> | ||

{{Outro664}}{{top}} <!-- for previous episodes, use the appropriate outro, found here: https://www.sgutranscripts.org/wiki/Category:Outro_templates --> | {{Outro664}}{{top}} <!-- for previous episodes, use the appropriate outro, found here: https://www.sgutranscripts.org/wiki/Category:Outro_templates --> | ||

== Today I Learned == | == Today I Learned == | ||

* Fact/Description, possibly with an article reference<ref>[url_for_TIL publication: title]</ref> <!-- add this format to include a referenced article, maintaining spaces: <ref>[URL publication: title]</ref> --> | * Fact/Description, possibly with an article reference<ref>[url_for_TIL publication: title]</ref> <!-- add this format to include a referenced article, maintaining spaces: <ref>[URL publication: title]</ref> --> | ||

Revision as of 21:27, 4 November 2022

| This episode was transcribed by the Google Web Speech API Demonstration (or another automatic method) and therefore will require careful proof-reading. |

| This episode is in the middle of being transcribed by Hearmepurr (talk) as of 2022-10-31. To help avoid duplication, please do not transcribe this episode while this message is displayed. |

Template:Editing required (w/links) You can use this outline to help structure the transcription. Click "Edit" above to begin.

| SGU Episode 889 |

|---|

| July 23rd 2022 |

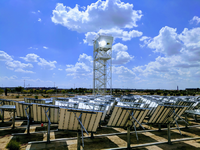

Solar Tower Fuel Plant |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

BD: Brian Dunning, American writer and producer |

| Quote of the Week |

Scientific principles and laws do not lie on the surface of nature. They are hidden, and must be wrested from nature by an active and elaborate technique of inquiry. |

John Dewey, American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction, Cara's Return, Post-Op reflections

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Thursday, July 21th 2022, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening folks!

S: Cara making her triumphant return. (collective happiness noises)

E: Blow the horns.

C: Hey everyone this will be, this is the first time I've sat in my office chair since my surgery. We are officially on post-op day. What would that be? 15. I have to say it's pretty nuts how quickly you start to feel better. Like the first few days are brutal torture and then you turn a corner and it's like there are moments when I forget that I had surgery and I have to be like oh yeah Cara don't try to pick that thing up or like you need to slow down a little bit. Because my body doesn't feel anymore like I'm post surgery until I push myself and then I get so tired so fast. That's like the main lasting thing. It's fatigue and my sleep is completely effed. It's like I have crazy and it's funny because I've posted about it and people are like oh yeah I remember that. Like when is night? When is day? I just sleep when I'm tired so it's like crazy. But yeah it's mostly just I'm tired all the time and everything wears me out. And it's still kind of hard to find a really comfortable sleeping position. But otherwise I feel pretty good.

S: That's great.

C: Like I was up and walking super fast. I went home the day of, and we got some interesting emails from people asking about that.

B: Day of?

C: Yeah. Just a few hours after surgery. We got some interesting emails of people from other countries being like, what? What are you doing in America?

J: They'll kick you out of the hospital like 13 minutes after the surgery's over.

C: I know.

S: But you know what? The outcomes are better when you do that, though.

C: That's what I'm saying.

B: Yeah. Bottom line.

C: I'm glad. I don't want to spend the night in the hospital.

E: I don't want to be there.

S: Yeah, you don't want to be in a freaking hospital. It's a dangerous place.

C: Yeah.

E: There are sick people there.

B: People die there.

C: It's full of infection, and also they wake you up at ungodly hours because it works for the rounding schedules, not because it works for your health.

S: I know. But when you're in a hospital, they're obligated to do certain things. You're going to get your blood drawn every day. You're going to get your vitals done every shift, whatever. And there's just lots of beepers and stuff going off, alarms and everything. There's other patients. It's just a horrible place to sleep. You can you know we do. We are as protective of sleep as we can be. A lot of orders are while awake. Do this every so often, but only while. Don't wake the patient up to freaking do this. Especially post-op. If you're in the hospital, it's going to be a little bit more intrusive. But it's also, there's a lot of really resistant bugs in the hospital. You don't want that.

C: Yeah. And you've got open wounds after you get out of surgery. Like yes, they're closed and they're bandaged and everything, but you've got a line in your arm. And for a lot of people, they have drains and tubes and things too. Luckily, this surgery doesn't necessitate that. So the only open line I had was my IV. But for some people, they've got lots of potential sources.

S: But if you have drains in or if they had to actually open up a body cavity, whatever, then you need to be in the hospital until that heals.

C: For sure. They're not gonna [inaudible] you.

S: But with the newer surgeries that are so much less invasive, if you don't have anything like that, they want to get you out of there fast.

C: And you guys should see my wounds. I can text you a picture, but the incisions are tiny.

S: Yeah. That's awesome.

C: They're like a centimeter, maybe two. They're so small. And it's like incredible that, you know, a friend of mine was so confused because her friend recently had laparoscopic gallbladder surgery and she was like, how are they so small? How did they pull your uterus out? And I was like, you know, that's not where they pull your uterus out from. That's why hysterectomy scars can be so tiny because they do all the work through the holes, but then they remove the organs through the vagina, which is, you know, the easiest way to do it.

S: It's a vaginal hysterectomy.

C: Yeah. Yeah. And so the laparoscopy is just all the tools. It's the light. It's the little cutter and─

S: So they could see what's going on.

Special Segment: Cara's Cancer Experience (4:33)

C: Yeah. But so they go in with all that. They cut everything loose and then they pull it out the bottom and then they sew it back up. So what I have to remember and what my gynecologist told me at my one week postop was basically she said there are two rules. That's it. She said no sex for like forever. She was like just for a really long time and I was like, yeah, I'm not planning for like several months. She was like, great. And then the second one is no baths and no swimming for four more weeks after my postop. So that would be five weeks post surgery. But I was like, I was asking her, you know, because you hear all these things like don't lift more than 10 pounds and don't blah, blah, blah, and don't walk farther than whatever. And I was like, can I harm myself without knowing? And she was like, no, you'll know. She's like, it'll hurt.

S: Yeah.

C: You know, she was like, don't do anything that hurts. I was like, okay.

S: If it hurts, don't do it. That's an amazingly useful piece of advice. I know it's kind of a cliche.

E: It's not just a doctor joke thing.

S: No, it's real.

C: No, but it's true.

E: Doctor, it hurts when I do this? Don't do it.

S: Acute pain is a warning that you are causing tissue damage, you know?

C: Right.

E: And what's the condition some people have where they can't feel pain?

C: That's super rare.

E: That is horrible. Oh my gosh. I feel terrible for those people.

C: But also you think about it and that's sort of what it's like if you're taking too many pain meds as well.

S: Totally.

C: So I'm really glad. So here's the crazy thing about my situation. I didn't take any opiates at all, not even in my IV.

S: That's good.

C: And each time they asked me, how's your pain? I was like, I can't tell. I think it's fine. And they were like, okay, we're just going to keep you on Toradol then, which is just a really strong NSAID. And that seems to be all I needed. And I wasn't trying to be a hero or anything. It was kind of annoying because so many people were like, don't be a hero. Take the pain meds. And I was like, I'm not trying to be a hero. I'm afraid of pooping. I can handle this pain. But what I won't be able to handle is constipation at all. If I was in a comfortable position, my pain was like a two. If I shifted the wrong way or I used my abs at all, it shot up to like a seven or eight. But I very quickly learned how to move the right way, how to use my arms to facilitate getting up and down out of chairs. And we put bars on the toilet, which was hugely helpful. The hardest part was getting in and out of bed. I mean, that's nearly impossible when you have any abdominal surgery.

B: That's an easy problem to have. I mean, I just stay in bed.

C: Exactly.

J: Cara, how long until you're tip-top?

C: I mean, it's hard to say because I feel much better now except for the fatigue. And they say that that can last even beyond like when you're better. They say at four to five weeks is when you, well, four to six weeks is when you can start like doing light exercise again. I was relatively healthy before the surgery. I followed doctor's orders and got up and walked a lot and just really listened to my body. So I think I'm doing well. I just have to remember I'm not healed on the inside.

S: Right. The fatigue is an interesting phenomenon because like you're tired on a cellular level. You know what I mean? It's not like you just worked out that kind of tired where you just need to relax. It's like your cells don't have energy. It's like, Jake, when you were like really had the bad COVID.

B: ATP.

S: Yeah, it's just like you have this crushing fatigue that goes beyond being tired from physical activity because, you know, when you're getting surgery, that's a huge stress on the system.

C: Yeah.

S: From multiple ways.

C: And when you're asleep, you heal better. Like when you're dead asleep, your body is using all of its metabolic resources just for healing and for, you know, basic life functions. But you're not walking. You're not moving. Moving is really intensive. But yeah, I'm feeling a lot better. I'll tell you a couple kind of fun things about the actual experience. I know some people have written in asking about anesthesia and asking about, you know, just different aspects of things. So I will say that last time, if you guys remember my last surgery, which was a leap in DNC, I had not a great anesthesia experience. And so that was a big part of my anxiety and fear leading up to this surgery. I'm proud to announce that my anesthesia experience was 100% better this time.

S: That's good.

C: It was like night and day.

E: Oh, good.

B: Twice as good?

C: Yeah, I mean, yeah, exactly. A, because I think that I had a great anesthesiologist and B, because I think I learned a little last time, because last time was my first surgery. Number one, for the nausea, vomiting fear, which is a legitimate fear in surgery, they will often do things to try and mitigate that. They'll give you Zofran or Reglan or different drugs to help reduce vomiting because it's dangerous to vomit after intubation. So and a lot of people feel quite nauseous from or nauseated from anesthesia.

B: Thank you.

C: So I was really. Yeah I know. So I was really scared of that. And my anesthesiologist the first time was very kind about it. He was like, it's a legitimate fear. It happens to a lot of people. We'll do what we can to manage. And I was like, great. So he was like, I'm going to give you a Zofran-pepsid combo. I was like, that sounds awesome. And my nausea was there, but I didn't puke. But I was like, what should I do after the surgery? And he was like, wait until the last possible minute to eat, until you can't stand the hunger anymore. And I was like, okay. That was terrible advice because that made me feel so much more nauseous. Now this time I was like, I'm going to try and just test the waters and eat some crackers or bread right away. And I did that and I had no nausea because you get sometimes nausea is from an empty stomach.

B: Oh, wow.

S: It's individual in fairness.

C: It's totally individual, which is why a blanket statement like just don't eat, I think is dangerous. I think it's really listen to your body.

S: Yeah listen to your body.

C: And make sure you're in a safe space that if it does induce vomiting, you're able to do it safely, whatever. But it didn't. I was totally fine. Also this guy gave me more goodies. He gave me Reglan, Zofran, and some steroids. And they even gave me a little boost before they took out my IV because they had one last dose standing. And that helped me with any car sickness on the ride home, which was great. So there was that. The other thing is, and this is a huge thing that Steve and everyone else, I want to study this. Like after I finish my PhD, I think I want to do a research study. Actually, I should dig deep to see first if there's literature on this already. But okay, so the first guy, I was like, I'm super scared. And he was like, that's normal. It's okay to be scared. We'll give you a little dose of a benzodiazepine right before we give you the rest of the cocktail in the OR, which means I rode to the OR in the bed. I got on the operating table by myself. I was awake when they put on all the monitors. They put on the compression booties. They did everything. And then, and actually, I think I told you guys this last time, but at one point the nurse was, it was just me and the nurse in the OR before all the doctors came in and somebody came in on the intercom and they started to talk and the nurse ran to it faster than I've ever seen her run and was like, patient in the room. And I was like, what were they going to say? So anyway, it was pretty funny, but I was fully alert before then. And then the doc, once the anesthesiologist came in, he said, okay, you should start feeling better right about now. He pushed the Versed and then I don't remember anything. This time I told him I'm scared. He said, great. After you talk to the docs and stuff, I'm going to hook you up. And I was like, okay. So I'm in the room with the doctors, the nurses, everybody's there. And he walks in with a big ass syringe and I was like, is that the Versed? And he was like, yup. And he pushed it and I don't remember anything after that.

S: That's the memory wiper right there.

C: That's the memory wiper. So he did it in my pre-op room, not in the operating theater. And I have a sneaking suspicion, and this is a total observational hypothesis that I would love to study systematically. When you first wake up in post-op, the last memory you have is the last memory you have. And if your last memory was in the operating theater, it can be somewhat traumatic for some people. If your last memory was cozy in your room with your blanket and your pillow and the warm smiles of everybody around you, I think that can be a lot less traumatic. And I'm curious if pushing Versed earlier isn't better for post-op recovery and psychological benefit.

J: They always, you know, like I've had surgeries, you know, Cara, you and I talked about this. For some reason, like my experience is they always talk to you when you're in the surgery room. There's always some type of conversation going on in there. When I'm getting surgery, I don't know why. I like your idea. Knock me out.

C: But on Versed, that's the thing that's interesting. On benzodiazepines, you're not like trashed. You're pretty coherent. You just don't remember it at all. And so if they push the benzodiazepines early so that you're A, comfortable because that's what they're for, they make you feel really relaxed, you're totally, I mean, you're not totally coherent. They want to make sure you sign all the paperwork before they give you that, which you have to do. But when they push them, they can do that then take you into OR. You can still have fully fledged conversations with them. You just can't consent to anything because you're technically like on hard drugs. But like they told me that I was being totally normal. Like I reminded them, hey, we can't bring my pillow in. Here nurse, do you want to take this? And I told them some story about a woman I talked to who at Sloan Kettering walked her way into the OR. Like they were like, yeah, you were completely there. You were just chill. You said the minute they push the drugs, I go, oh, I feel better. I literally said that. I think I'd be curious from a psychological standpoint, who benefits or what's more beneficial? Having your memory wiped slightly sooner and just never being cognizant of the operating theater. I don't know. I don't know.

S: Yeah. Interesting study.

B: When I had a procedure relatively recently, I liked the operating theater. First off, it was like the bridge of the enterprise in a sense with monitors everywhere, all these technical doodads, and then I had like a cool conversation with one of the doctors. It was like a pro-science, pro-skeptical thing. I was like, this guy's really cool. And then that's the last thing I remember. That was a good memory. But then my procedure was nothing compared to yours though. So it's hard to do a real comparison.

C: Yeah. You did like a, I think we talked about this, that was more like that Twilight anesthesia. Like what's it called?

S: Conscious sedation.

C: Conscious sedation?

B: No, I was out.

C: Oh, you were out. Oh, okay.

B: This was for the whatchamacallit the butt procedure that I was out.

C: I still think, Steve, am I wrong, endoscopy, even though you feel out, it's not conscious sedation, but it's like twilight, right? It's not like propofol, is it? I guess it varies.

S: The question is, were you intubated? If you were intubated, you were out. That was full and a general anesthesia.

C: You probably weren't intubated.

S: If you're not intubated, it's conscious sedation. That's a good rule of thumb.

B: It seems like a misnomer though, because you are not conscious.

S: Yeah, it is. You're not conscious.

C: You also don't remember anything, so even if you're pseudo-semi-conscious, you won't remember any of it.

B: Oh.

E: Cara, you were intubated?

C: Oh, yes. Absolutely, I was intubated.

E: How did your throat feel afterwards? Did you have pain?

C: Horrible. Yeah, horrible, for days. That's why I couldn't really eat crackers. The first day, I had bone broth and some bread. Oh, I bought some of those Hawaiian rolls at the grocery store at the last minute when I was grocery shopping for my mom to come in town before the procedure, and those were a godsend. Those things are just amazing. You guys know what I'm talking about, right?

J: A Hawaiian roll?

E: I don't know. We don't know it as a Hawaiian roll. We might know that.

C: Oh, really?

S: Is it sushi?

C: No, no, no. They're bread.

S: Oh, okay.

C: They're like these little rolls, bread rolls that are slightly sweet and they're super soft.

S: Sounds good.

C: Yeah, because crackers─

E: Like a challah bread? Do you know what challah bread is?

C: It's Hawaiian bread. I guess it's a West Coast thing.

E: Yeah, I don't know.

C: Yeah, because crackers are so bland and easy, but they hurt your throat. They're hard to eat.

E: Oh, they're scratching.

C: Yeah, the soft bread was great. Also, they busted my lip. I don't think they realized it, but you know when they intubate, they use that big metal thing?

S: Yeah.

C: He may have stuck my lip between my tooth because I had a really fat lip when I woke up from surgery, and it took about three days for that wound to heal. So I can answer more questions if you have any, but I think the most important thing that I want to mention before anything else is the pathology. I want to give you guys a report on what was going on with that and what we learned, and just to reinforce to all of my listeners who have a cervix why it is so important to do your annual, or whatever your calendar is, but to do the screenings that are recommended. If you guys remember, my last surgery was a DNC and a leap. DNC dilation and curettage is like a scraping of the endometrium, which is the inner lining of the uterus. It's also often an abortion procedure, but in my case it was just used to test the tissue to see if it had any dysplasia or neoplasia. A leap is a loop electrosurgical excision procedure. So this is a wire loop that has an electrical current that goes through it where they cut a chunk of your cervix out. I want to go back a little bit. I have long had abnormal paps, and whenever I had an abnormal pap in the past, it was recommended that I do a colposcopy. Colposcopy, which sounds like endoscopy, is a scope, but it's a colposcope. So it looks at your cervix, not your intestines. Colposcopy is a little bit of a misnomer because it almost always includes also a biopsy. So it's not just a scope. Very often they have to take a punch biopsy, and just so you men know, they do not give you any drugs for this.

E: They cut you with no drugs.

C: Yeah. I'm talking about Advil. There's nothing. There's no anesthesia. There's no nothing. I mean, you could take Advil on your own, I guess, but they open you up with a speculum. They shine a light. They do a vinegar wash to see if your skin reacts, to see if there's dysplasic spots, and then they literally have this tool that looks like really long scissors with a little punchy thing on the end, and they go cut, cut. Usually they take two, and then they do what's called an ECC, an endocervical curettage, which is that scraper again, but they do it inside the endocervix. I've had to have, let's say, five of these in my life, maybe more, and they're brutal. And for some women, they're well-tolerated, but for me, they're very painful. And it was getting to the point where I couldn't handle it anymore. And I had begged and pleaded my doctor, I said, can we just do a leap? And she's like, you don't need a leap. They always come back negative. I'm not going to remove perfectly healthy tissue from your cervix just because you don't want to have these biopsies, because the reason, my reasoning, of course, was that most women, this is the standard kind of progression of cervical cancer or of precancerous cells for most women, it's the squamous tissue. So it's kind of like the outer layer of the skin cells of your cervix. That's what usually has dysplasia or neoplasia first. So they do a biopsy. They see that it's what's called SIN 1 through SIN 4. Those are basically the stages of precancerous cells. In early stages, they might wait and see. In later stages, then they'll do a leap or a cone biopsy. I never had dysplasia, so she was never going to run ahead with a leap. But my reasoning was, well, if we just remove the tissue, it might not come back abnormal anymore, right? But she's like, I'm not doing that. So she said, you know, next time we'll talk about maybe doing some sort of conscious sedation or something to make it more manageable. It's like, OK. And then as a fluke, on my next pap, I had a result of abnormal glandular tissue. Now, squamous tissue, like I mentioned, is the outer layer of the cervix. It's kind of like the skin cells of the cervix. Glandular tissue is deep inside the cervix and moving up into the uterus. These are the glandular cells. An abnormal glandular tissue result is much more concerning. So that's when you have to go straight to a DNC. The standard of care there is a DNC. So she's like, we got to do a DNC. I know that the biopsies haven't been well tolerated. Why don't we do this under general anesthesia? And I was like, can I do a leap? And she was like, technically, the order would be DNC, another colposcopy, and then if the colposcopy is positive, then a leap. But because you've been so adamant and because we've done so many colposcopies and we're going to put you out anyway, let's just do a leap. But she was really concerned that she was skipping steps and going outside of the Bethesda protocol, which is the standard of care for gynecologic surveillance. But we both decided together, let's just do the leap. OK. Cut to the results from the last surgery, DNC negative, ECC negative, leap positive. So if you look back at six or seven screens that I've had over the years, the only thing that came up with adenocarcinoma in situ, which, by the way, has blown past the four stages of cervical dysplasia of squamous tissue. Now we're talking basically cancer stage zero of the cervix. The only test that showed that was the test I was never supposed to get. Every other protocol screen came back negative. So then the standard of care has to be hysterectomy. If you have adenocarcinoma in situ, you will have to get a hysterectomy because if you leave it alone, it will become invasive adenocarcinoma. It's not an if, it's a when.

E: So are you saying, Cara, that this was caught as early as it possibly could have been?

C: It was not only caught as early as it possibly could have been, it was caught as something of a fluke. And my doctor said to me, point blank, Cara, if you hadn't advocated for yourself, I think you would have woken up in a few years with invasive carcinoma.

E: Oh my gosh. And how many women cannot advocate for themselves?

C: Right. Either don't have─

E: The vast majority.

C: ─either don't have the medical knowledge or─

E: Right. Or somebody who can help them.

C: ─are scared or there's a language barrier, you know, whatever. They're not getting these screenings. So I know I'm a bit of a flukey case. I had a weird presentation. So it was two things. One, I advocated hard for myself. And two, I was very up to date with all of my screenings. Because I've had so many abnormal things in the past, we've been super, super vigilant. Ultimately, you know, I had the hysterectomy and the pathology report came back. The fallopian tubes were clean as we expected. We never had any worry about those. The uterus was clean, as we mostly expected. But the cervix had even more AIS in it. So we know we didn't remove it all from the leap. We know doing the hysterectomy was absolutely 100% the right thing to do. Because if we hadn't done it, that AIS would have transformed into invasive carcinoma.

E: Oh my gosh.

C: And in somewhere from one to five years, I very likely would have cervical cancer. And I'm talking the real deal radiation, chemotherapy.

S: Yeah, you dodged a bullet.

C: Huge bullet.

E: Big time.

C: I mean, it's incredible. And it just goes to show how important it is, you guys. And what I mean is you guys, girls, you every everyone's, how important it is to follow the standard recommendations. And if something seems wrong, or if something doesn't feel right, or if you're confused, or you have questions, to take the time to ask them and to really, really understand what's going on with your body. Because as amazing as our medical establishment can be, and I'm lucky, I feel like I have one of the best gynecologic surgeons, I happen to be lucky that my gynecologist is also a premier laparoscopic surgeon, and that she's just incredible. She's super progressive. She's very warm. She's intelligent. She's ultra skeptical. But not everybody has that opportunity. And even with the best of the best of the best, they're your only gynecologist. You are one of hundreds of their patients. And nobody is going to advocate for you better than yourself. And so I just really wanted to reinforce because, gosh, I mean, I burst out in tears when she said that to me in the doctor's office. She was just like, Cara, thank goodness you did this and we did this together because we know what the outcome would have been otherwise. Yeah. So there's that. That's where I'm at.

E: Is there this history of cancer in your family, I mean, what can people do in order to kind of─

C: Oh, gosh, no. This is 100% human papillomavirus. I can tell you point blank. And the vast majority of cervical cancers are, the vast, vast, vast, vast majority. So this is not a BRCA1 thing. My family is not a cancer family. I'm very lucky in that respect. My father has prostate cancer, but found it in stage one, removed his prostate, and is completely clear. And that's just one of those things, the longer you live, the higher your risk. But we don't have a lot of cancer, like genetic cancer concerns. But I'm of an era. I'm 38 years old. I was born in 1983. The Gardasil vaccine did not exist when I was a child. So most kids now get it when they're young. It didn't exist when I was a child. And as it came on the market, from an insurance perspective, I was always just outside of the age bracket. I was just too old for my insurance to cover it. And only within the last several years did they expand coverage up to 45 in the US, which meant that I was able to go and get it. But by then, I already had HPV18. So I'm now protected against eight other strains. It's a nine-valent vaccine. HPV18 is one of the high-risk strains it protects against, but I already have it. But I'm now protected against the other eight strains. But HPV18 is a very cancer-causing strain. Most people, and don't get me wrong, if you have it, you're very likely fine. The vast majority of people clear it on their own. But some people don't. And it turns into cancer. Or I should say it causes cancer. The virus doesn't turn into cancer. But this is very common, you guys. And another thing that I think a lot of men don't think about, it all falls on the woman a lot. And there's a lot of slut-shaming around, like, oh, the woman has HPV, oh, the woman's getting cervical cancer. Men carry HPV. That's how women get HPV. But men do it willy-nilly because there's no real test, they don't ever have symptoms unless they have one of the few strains that cause genital warts. The vast majority of the strains, the only real negative consequence is cancer. And that really happens much more readily in the cervix. Although some men can get throat cancer and anal cancer from it. And women as well. Yeah, it's one of the main causes behind throat and anal cancers as well. But it's by far the reason that most women have cervical cancer. And if you have, like, a grandma who died of cervical cancer, she probably had HPV. We just didn't know about it back then. So that's the other thing. Like, if you're having positive HPV tests and abnormal PAPs, you've got to be vigilant. And when your doctor says every six months or every year or whatever their recommendation is, follow it. Follow it.

S: Well, Cara, I'm glad you're doing better. I'm glad it all turned out well in the end.

C: Yep. Got about a month left until I feel like I'm, like, completely 100%, but so much better.

S: You're going to join us for Science or Fiction at the end of the show.

C: Yeah.

S: And we're going to move on with the news items without you, but we'll talk to you at the end of the show.

C: Yeah. And then next week I'll be back, I think, full time. No problem.

S: Full time. Awesome.

C: Yeah.

S: All right. Talk to you soon.

C: Thanks.

E: See you in a bit.

B: Bye, Cara.

News Items

Global Warming Technologies (27:50)

S: All right, guys. To start out the news items, I'm going to talk about some global warming mitigation technology. This is something that we talk about occasionally, but there are a couple of ones I want to add. Jay, you talked about green steel. It's about 10% of carbon emissions come from the steel industry. And we could find ways to make do with using hydrogen and electricity instead of fossil fuels and coke. So there is two more I want to talk about that I thought are pretty cool. One is a method of making carbon neutral jet fuel because jets, we're not going to have electric jets anytime soon. (Bob laughs) I know that they're working on it. They are working on it. They do have like an electric jet engine. But the thing is, it's just not going to be able to have the range.

E: Wouldn't it be a hybrid anyways?

S: Yeah.

J: It's a hybrid.

S: At first, definitely you would have you would use hydrocarbons to get into altitude because that's where most of your energy is used anyway.

E: And then switch over.

S: And then maybe you could switch over for cruising. But still, that also means that it's not as useful because you're only replacing a minority of the energy.

E: Right.

S: But it's something. Something's better than nothing. So maybe we will go to hybrid jets for a while. I think we need a lot of advancements in battery and electronic technology before like they're going to be entirely electrical. But if we could make carbon neutral hydrocarbon jet fuel, then that could be a way of making the commercial aviation industry.

E: That sound nice.

S: So there's been a lot of talk with biofuels and we can't technically do this now. It's always a question of doing it at industrial scale and economically feasibly. Biofuels I think are always going to have a very, very limited place in our energy future because of a lot of the feedstocks are land intensive. There'll be some you could do from what was otherwise waste or growing algae and bats or whatever. So we will have some of that, but we're not going to be able to use millions of acres of land to grow feedstock for biofuels just just don't have it. But this uses a different method. This is a new method. It's a an all in one system. So you have a tower and the tower has the material and the chambers in order to have a what they what they're calling a consecutive redox cycling. And essentially it's a way of turning carbon dioxide and water, H2O, using the energy from solar heating in order to make hydrogen and carbon monoxide. When we're talking about biofuels and generating any kind of fuel from electricity or from clean energy source, hydrogen and carbon monoxide are commonly the intermediary molecules or in the case of hydrogen, it's the final molecule because they're both high energy molecules. And once you get to either hydrogen or carbon monoxide, you've done it. You've got your high energy molecule. And then the subsequent reactions in order to make whatever it is you want to make are the easy part then from that point forward. In this case, they go through hydrogen and carbon monoxide to either kerosene or diesel fuel so they can make both with this process. Kerosene is a high energy hydrocarbon which you can use in jet engines. And in fact, it could be fed into the existing infrastructure from storage to distribution to burning it in jets.

E: So the engines can accept it without damage without.

S: Yeah. From what I'm reading, yeah, they can. Maybe it's not all of them. But whatever, your typical commercial jet engine can burn kerosene. The entire process has an efficiency of 4.1% and they're hoping they can get it up to something closer to 15%. But even at 4.1%, it's still viable in terms of an industrial process. So anyway, they've built this is a the first the news item here is that they've gone for the first time from the lab to a demonstration production. They built the tower, they built the solar energy array, and they're making kerosene and diesel fuel with this method. So again, this is like one of those things, whether or not this will eventually be a significant player, it's hard to say. But it's good to see that these kind of technological advancements are continuously being made. The next one is I thought was just really clever, kind of fun to talk about. And it's a way of recapturing the energy lost to breaking trains, meaning, slowing that decelerating trains. So trains are heavy, they go fast, so they have massive momentum. And there's a lot of kinetic energy in that momentum. When trains slow down or break, that energy is just completely wasted as heat. It's a total loss. Here's a fun fact, what is the amount of energy lost in the world through breaking of trains? So I want to ask you two ways. One is when a typical passenger train goes from cruising speed to a stop, how much energy does that just one time? How much energy does that represent?

B: Forfeit one.

S: So we're going to put this in representative units will say, how many days of electricity for an average American home?

J: I'll say three days.

E: I will say 10 days for one household.

B: So I'll split the difference, say a week.

S: 20 days.

E: Wow.

B: Should've said 11. (Evan laughs)

S: 20 Average American homes for an entire day or one for 20.

B: Nice.

S: Yeah, that's a lot of energy. That's a lot of energy. If you can capture it all.

E: Yeah, well, that's the rub.

S: There's another way to look at it. If you look at all the trains in the world and all the breaking events for all the trains, how much energy is that?

J: Wow.

S: The units we're going to use for this is the energy produced by the Hoover Dam.

B: I think I just figured out what's causing global warming.

E: How about 100 Hoover Dams?

S: Very close. I'll just stop right there. One hundred and five. You're very close.

E: Wow.

B: I was going to say 104. (Evan laughs)

S: One hundred and five Hoover Dam's worth of energy.

E: Damn.

J: That's amazing.

S: Yeah. So that's a lot of energy. Now, of course we're never going to capture all of it. But we already have the technology to recapture most of that energy through regenerative breaking. We don't even have to invent a new technology. We just need to just install them on trains. The real question is, what are you going to do with the energy?

B: Charge a battery.

S: Yeah. So you could say we'll charge a battery. That's what we do with cars. So that means you need enough batteries to hold 20 days worth of power for a typical American home.

E: That's a lot.

S: That's a lot. That's massive. And that's just for one breaking event. So the assumption would be that you then use all of that energy in order to get back up to speed. So that would be the simplest thing to do. You basically have one car on the train that's a battery. You store it up when you break and then you release it. If you have an electric train of course, you don't have an electric train, then you can't do that.

E: Right. Yeah.

S: So for those trains that are not electric or let's just say it's not feasible or practical or cost effective to have enough battery to capture all of that energy, what else could we do with it? Can't really send it to the grid because the train's moving. So here is the clever bit. This is what one company figured out how to do.

B: We could heat all the seats in the train?

S: Well, you could do a lot of things. What they want to do is attach a car to the train to every train that has the equipment on it necessary to do carbon capture. And then you could use the electricity generated, the energy generated from regenerative braking to run the carbon capture on the train. Part of the reason why this is so clever is because we can do this now. We can capture carbon from the air, right? You just have a process that─

B: Companies are doing it now.

S: ─chemically binds the carbon. But in order to make it function, you need giant fans blowing air through the apparatus. And that uses up a lot of energy. But if you have a moving train─

B: Sweet.

S: ─you don't need the giant fan to use the trains moving through the air. You don't need to move the air over the chemical reaction.

B: Bonus.

E: So it gobbels it up as it goes.

S: Yeah, so that's the idea. You just have I guess you'd have to have some batteries to buffer it and to keep it going. But you don't necessarily need to capture all that energy because you could use it as the train is braking. Yeah. So they did some calculations based upon the efficiency of the equipment and how many trains there are or whatever. They said this is a Professor Peter Styring. He's one of the researchers working on this. And he said that just in terms of how quickly they could deploy these, that this technology has the potential to reach annual productivity of 0.5 gigatons by 2030, 2.9 gigatons by 2050, and 7.8 gigatons, this is of CO2 of course, by 2075, with each car having an annual capacity of about 3,000 tons of CO2 in the near term with the technology in its current form. That's a lot. That's not an insignificant amount of CO2. So the amount of CO2 released per year is 36.7 billion metric tons. That's a gigaton. So 37, basically 37 gigatons. And this could capture 7.8 gigatons by 2075. So it's not insignificant. Let's put that 20% and by 2050, maybe 10% or 8% or so.

B: So what's the return on investment, like what's the cost compared to these facilities that are dedicated to carbon capture?

S: Think about how much energy it costs to build the Hoover Dam how much money it costs to build it, like 70 million. The energy equivalent of 105 of them it probably is in the same order of magnitude in terms of they say it's cost-effective in terms of the capital investment to do this. So you think about where we're going to be in 2050 and all the things we got going on. I mean, ideally, when we talk about being net zero in 2050, that doesn't mean we've decarbonized everything, all of our infrastructure, all of our transportation, energy production, steel production. It just means that it's low enough that we're offsetting the rest with carbon capture.

E: Right, capture as much as we produce.

S: If we get down to say 10% of where we are right now, and then we could use this to capture 10%, that same amount, that could get us to net zero. I don't think that's going to happen, but that's sort of the goal, and it's certainly feasible. But we're definitely going to need to do some carbon capture on this level in order to get to net zero, because we're not going to 100% decarbonize all industries. We're going to have to be capturing some carbon. But the bigger point here, we can combine this with the green steel thing that we talked about before, just a lot of news items that we talk about, is that right now we have the technology to get to net zero. We have it right now. Electric vehicles are now cheaper to operate, cheaper to own and operate than internal combustion engine cars. They're a better driving experience. It's just a better technology. We still need some infrastructure, et cetera. It's not for everywhere, every place. If you're in a part of the country where it's hundreds of miles in between civilization, it may not be that practical. But then you can get a hybrid and get 90% of the carbon savings. So between hybrid and full electric technology, we could mostly decarbonize our transportation sector. We could 100% decarbonize our energy infrastructure if we wanted to just build all nuclear hydroelectric geothermal solar wind, that's it. If we wanted to completely replace fossil fuel in our energy infrastructure, we have lots of options in terms of decarbonizing steel making and decarbonizing─

E: Concrete.

S: ─cement. Yeah concrete, cement making. We also have lots of options for making green hydrogen and carbon capture. Definitely we need to continue to incrementally advance all these technologies in addition to grid storage. But what we have right now, we could do it if we wanted to. So then really the question becomes economics. A lot of these things will require a massive infrastructure investment or industrial investment. But compare it to this. The economists estimate, there's a bunch of economic analyses out there, but here's a few representative ones. Global warming could cost the U.S. economy $14.5 trillion by 2070. By 2100, it could be costing the U.S. economy $2 trillion per year. And the world economy could shrink by $23 trillion by 2050 due to climate change. 23 trillion. So if we invest 10 trillion, that's a massive infrastructure investment, $10 trillion. And that's less than half of what we'll lose if we don't do anything about global warming.

B: Half we'll lose per year.

S: Yeah. The order of magnitude that we're talking about. It's more costly not to make these investments. And frankly, in terms of, I've been reading a lot about this recently, I've always been sort of lukewarm on the carbon tax idea, but bottom line is I think the economists are coming to the conclusion that we need a carbon tax. It's really the only thing that's going to really push us over the edge. Politically, economically speaking. We don't have the technology. We just have to make the mitigation options economically competitive. And the way to do that is to not allow fossil fuel producers to externalize their environmental costs. And the way to do that is to tax the carbon.

B: Yes. Get real with them.

S: And the way to do that is to tax the carbon. So if you tax the carbon so that there's a level playing field so that you're paying the actual real world costs of your technology, of your products, then all of these options suddenly become economically viable.

B: But it'll never happen.

S: Don't say never.

E: Well, yeah. I don't know. Maybe.

S: I'm not optimistic.

E: Not 10, 20 years ago, Bob. Maybe.

B: But not in the near future. Not in time.

E: We'll see.

S: We're too politically dysfunctional right now. Absolutely. But the way out of that political dysfunction, and I'm going to limit this to the U.S. now because I know every country is different. In the U.S., the way out of our political dysfunction is for the voters to educate themselves and to hold politicians responsible for these things. If people made climate change a priority, we could do it. We could fix this problem tomorrow.

B: It's simple, people.

S: The problem is the voters don't do that. The U.S. voters do not make climate change a priority.

B: Right. The U.S. voters have to stop being tribal with their political affiliations. And they have to eschew misinformation. Easy. That's so easy.

S: I didn't say it was easy. I just said it was possible.

B: I'm saying it's not easy, and it's not going to happen.

S: Yeah, but you know what? Things change. And public opinion sometimes can change very fast. If you think about for example, I know we're in a little bit of a pushback right now, but the classic example now is how suddenly public opinion about gay marriage changed, and then the impossible suddenly became possible.

B: Until the people that were then hiding have now come out of hiding. And we know how many there are.

S: Obama─

B: There's more now. There's more now that are obvious than there were the past 15 years.

S: I'm just talking about public support for gay marriage. Even Obama in 2010 could not unequivocally defend gay marriage. He was for the civil unions. Remember that?

B: Oh, yeah. That's right.

S: He had to take this wishy-washy middle position. And five years later, it was done. It was a done deal. Political opinion shifted significantly. And if we can have the same thing happen with global warming. If we can go from that 40% to 60%. Not just saying, yeah, yeah, I support mitigation and blah, blah, blah, but this is now a voting priority for me. I am not going to vote for a politician who's a global warming denier or who doesn't have a plan. That's what needs to change.

B: Yes. That would be a major hurdle that we could potentially get over. And that would be wonderful. But then, of course, you know what I'm going to say here, that that's only the first hurdle. That's only one country. We could make these changes. And that would be great and it would be beneficial. It would save lives. It would be the smart move. So many benefits for the United States and that would be great. But then all these other countries would have to do the same thing in order to meet what we want to meet. And it's just overwhelming to imagine.

S: It would have to be replicated in every democracy, but I think the U.S. has an impact. We have an impact on our allies. If we did it, we would speak with much greater moral authority when we have these climate summits. I know the elephant in the room is China and India, and they don't necessarily have to follow.

B: Yeah, and the string of reasonable administrations that the United States would have to have in a row.

S: Yeah. I know. I didn't say I think it's likely to happen but I'm just saying it could happen.

B: I'm just saying. I'm trying to make it a little real here.

S: It's sobering to think. It's interesting to think that that's really the only thing standing in our way. It's not technology. It's not economics. It's just political will. And it is like almost there. It's just not quite there. But of course, that little bit makes all the difference in terms of reality. All right. Let's move on.

SLS Launch (46:33)

S: Jay, I understand that the SLS might actually launch in August.

J: And NASA recently announced that they're making progress with preparations for the Space Launch System rocket and the Orion spacecraft. Did you hear what I just said?

S: Yeah.

B: Yeah.

J: So they said that it seems likely that a launch could happen later this summer. And the truth is that they actually even gave a date. The earliest the date could be would be August 29th. So the current plans now state that the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft will be crawled out to the Kennedy Space Center launch site on August 18th. And if for some reason the August 29th launch window doesn't work, they have backup dates. They have one on September 2nd and they have one on September 5th. Now all these launch dates allow for the complete Artemis I moon mission. It wouldn't be like a different mission because the launch window changed. That's great. So here's what I'm talking about. They'll be doing an uncrewed command module going into lunar orbit for several weeks and eventually returning to Earth with a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. So of course, in order for this launch to happen all of the remaining testing and preparations, they need to run without a hitch. Even though there's not a lot left. There's enough where things could go south but they feel very good about it. And another big factor here, which is out of control of NASA, is the weather. Florida weather this time of year. It's kind of like the tail end of a bad weather season. So you never know. So keep in mind, this is the first time that they'll be actually launching this rocket. So the amount of preparation and testing is at a maximum. This is it. This is the maiden voyage. Between the three launch dates, the mission will either be 42 days or 39 days. That's the only difference. If the Artemis I mission goes well, then Artemis II missions could come as early as 2025. But let's not undercut how complicated and dangerous the Artemis I mission is. It has to successfully be launched with a new rocket system. That's huge. The rocket command module will have to successfully navigate the trip to the Moon. That's huge. They have to get into the Moon's orbit. I'm sure that's amazingly difficult. They have to leave the Moon's orbit, then they have to return back to Earth. They have to reenter into the Earth's atmosphere and then successfully do a splashdown. All of those things need to happen perfectly in order for them to do Artemis II. Keep that in mind. Stakes are very high. Among all the things that are left to do, one of the main ones is activating the SLS rocket's flight termination system. This is a system that can destroy the rocket. If it goes crazy when it takes off. It could be an amazing hazard somewhere because if you think about it, it's basically a bomb. So they plan to start activating this system on August 11th, which happens to be my birthday. So I'll celebrate the fact that they're turning on the flight termination system. So once NASA activates the flight termination system, they have approximately three weeks to launch the rocket. Guys, can you guess why there's a time limit?

E: Something decays. Something is evaporating the fuel.

J: Kind of, you're getting there. It turns out that it's because of batteries that power the system only last about three weeks and that system has to be operating on its own power. Can't be using the spacecraft's power.

E: They can't just run along 10 gauge, 120 cord out to the platform?

B: Just swap out the triple A's.

J: Those batteries! So if for any reason the flight termination system needs to be serviced, they would actually have to bring everything back into the vertical assembly building.

B: Oh, brutal.

E: Brutal.

J: So that's what they're testing now. So if that happens, then you could forget about any launch in August. It's going to be at the earliest sometime in October.

E: I'm sure they're also going to a time-lapse record the crawl of [inaudible]. I love that.

B: This would be great.

J: Now according to NASA, the vital pre-launch tests have been completed and approved and the vehicle is essentially ready to fly. The next thing that's going to happen is the rocket boosters will be brought out to the launch pad. And then on August 22nd, NASA will make the final go or no go decision. So we were going to know soon guys before you know it, before you know it─

B: It's coming up man.

J: ─we could be watching this thing fly. I am going to be riveted and I'm going to be nervous.

S: And excited. It will be generally exciting. So we'll be following it on the show very, very closely. All right. Thanks Jay.

Periodic FRBs (51:18)

S: Evan tell us about periodic FRBs.

E: Yeah. Here's the headline from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, their online newspaper. "Astronomers detected a radio "heartbeat" billions of light years from Earth." And I read that and my, in my head went that record scratch sound effect, right? You know that zzzyt sort of like. Whoa, gotta stop and pause and see what this is all about. And we've talked about fast radio bursts many times before on SGU. These are ultra short, ultra powerful pulses of energy. Some of the universe's brightest flashes that you can't see with your own eyes because they're detectable in the radio wavelengths. And they can travel billions of light years as the headline says. But we've also talked about ones that are actually kind of close within the Milky Way galaxy as well. So they're all over the place. But the energy is super concentrated. And I've seen it written many times that a single FRB can pack enough energy that would be the output of our Sun over the course of a hundred years. Whoa.

B: Damn man.

E: That's a ton of energy. But they're quick as snap. They blip out of existence in milliseconds after reaching the range that are detecting telescopes can capture them. They're happening all over the sky as well. A thousand times in any 24 hour period. And of course the astronomers do not yet know what exactly caused them. And generally speaking astronomers cannot predict where they will occur next. So they're happening but you have to have your instruments pointed at the right time in order to get them. Canadian astrophysicist Victoria Caspi describes FRBs as some of the most fascinating mysteries in all of astronomy. Yes, they are. And there have already been some FRB news reports this year but this recent announcement is exciting because they describe it as a clear and periodic pattern of fast radio bursts. As I said, the typical FRB lasts for a few milliseconds at most. This new signal persists for up to three seconds.

B: Wow.

E: Three seconds.

B: That's a huge difference.

E: Oh, it's enormous. What, a couple of orders of magnitude.

B: Yeah.

E: Yep.

B: Damn man.

E: Within that window the team detected burst of radio waves that repeated every 0.2 seconds in a clear periodic pattern with the peaks described as remarkably precise, emitting every fraction of a second. Boom, boom, boom, like a heartbeat. And it's the first time that, and they say that this is the first time the signal itself is periodic. And the findings were published in the journal Nature and it's authored by members of the CHIME, C-H-I-M-E, which stands for the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment and the FRB collaboration. MIT authors Calvin Lung, Juan Manapara, Caitlin Shin, Kiyoshi Matsui at MIT, and Danielle Micheli at McGill University. The researchers have designated this FRB 20191221A, and it's currently the longest lasting FRB with, of course, the clearest periodic pattern detected to date. So that's what makes this particular one very, very, very special. And it's happened apparently through, from what I can gather, I tried reading the paper to the best of my ability. What I'm able to glean from it is that it was three times that they caught this over the course of roughly three years. So it takes a long time for this signal to reemerge. At least at the levels that they're talking about between 2019 and 2021 are the three measurements that they were able to capture for it. Now, what do they think that this is? Well, they don't exactly know. Like I said, it's a mystery. But they suspect it could emanate from either a radio pulsar or a magnetar. Right, Bob?

B: Yes.

E: These are type of neutron stars. Extremely dense. Rapidly spinning. Collapse cores of giants stars. And they such, and this is right from the paper, "Such short periodicity provides strong evidence for a neutron star origin of the event. More over, our detection favors emission arising from the neutron star magnetosphere as opposed to the emission regions located further away from the star as predicted some models". So the magnetosphere, they think, may have something to do with this as well.

S: Neat. So that's going to help us understand where FRBs come from. What the mechanism of their generation is.

E: Yeah, that's right. And from what I read, about 5% of the FRBs that have been detected so far have some sort of repeating nature to them. Whether it's days, hundreds of days at a time. But those are the ones that you are able to study, predict, and glean a lot more information rather than just figuring out there was a one-off one back in 2016 that we just uncovered the data now. This happened. Great. But gone. And you lost an opportunity to study it. So these are the ones that they're really interested in being able to glean some hard information from.

Habitable Super Earths (56:40)

S: All right, Bob, finish up by telling us about haaaabitable super-Earths. "Habitable."

B: Habitable! Super-Earths, yes. In the news new simulations show that these gargantuan rocky worlds with hydrogen and helium atmospheres could sustain life for far longer than we thought possible. In some scenarios. This was published in Nature Astronomy. If you're not familiar with super-Earths, they're essentially planets bigger than the Earth up to 10 Earth masses. It varies but 2 to 10 Earth masses is essentially what they are. For the most part, they're considered rocky planets, but I guess they don't necessarily have to be. The name really applies to just the mass. Rocky worlds bigger than 10 Earths are called mega-Earths. And if they're mostly gas, then they're obviously called gas giants. Now, we obviously don't have a super-Earth in our solar system, but we see them a lot in many of the less fashionable parts of the galaxy. They're kind of all over the place. But just because they have the word Earth in their names doesn't mean they're habitable. (laughs) So can some super-Earths be amenable to life as we know it? So while most super-Earths are found very, very close to their host stars. Which is not good for maintaining an atmosphere. And I'm going to assume that life as we know it is kind of it's going to probably need an atmosphere. But this is really, though, the drunk looking for the keys under a streetlight. Our exoplanet detection methods, like the transit method, are best at finding big planets near their stars, so there's a bias towards that. So simulations, however, that show that super-Earths can form and orbit at vast differences from their stars. They don't need to be really close to their stars. And that would obviously allow for them to keep their large hydrogen-helium atmospheres without having the star, the nearby star, blowing it away. So they can have a nice thick atmosphere, so that's good. But what can survive in that atmosphere if it's all hydrogen and helium, right? I mean, that's not anything like our atmosphere. Is that even amenable to life at all? And the answer is yes. Bacteria and yeast for one, or I guess two, study after study shows that they, these microorganisms, can absolutely survive in such conditions. So that's not a problem. So that's checkbox two. So what's next? One of the critical components for life that's pretty much always mentioned is usually what?

E: Water.

B: Water is key. The presence of liquid water is obviously essentially paramount as far as we can tell with our one data point here. So anywhere you find water on Earth you're almost guaranteed to find some kind of life. Whether it's Jay or some extremophile microorganism, there's going to be life there. So can liquid water exist on the surface of a super-Earth? That's the next question. Can we have that? And to answer that, let's start with our Earth. Water has been on the Earth for four billion years. And there still will be liquid water on the Earth for maybe one and a half billion years, two billion years.

E: That's all?

B: Hard to be sure. Oh yeah, man. The Sun's just going to be getting hotter and hotter. Not from climate change. Just from evolution of our Sun. So yeah, it's going to get nasty. But hey, we've got another couple of billion years. So liquid water is going to have a good run on the Earth's surface. On its surface, which is important, for six billion years. Good decent span of time.

E: All right, I'll live with that.

B: To answer the same question for super-Earths, the researchers ran simulations. And they knew from the get go though that if you have a really thick hydrogen atmosphere, you're going to produce a really big greenhouse effect. And that's going to trap a lot of heat regardless of how far you are away. So their simulations had two sliding bars, if you will. One was for mass, which slid from one Earth mass to ten Earth masses. And one sliding bar was for orbital distance, which slid from one AU or, Earth-Sun distance, 93 million miles. One AU to a whopping 100 AU. So they fiddled with those sliding bars and they saw what they got. So the conclusions they came to was that these simulations showed that once you got past about two AUs or 180 million miles away, these super-Earths had liquid water on the surface that could survive from five to eight billion years, similar to Earth's. But the fun hadn't fully started yet. The fun really started when they basically removed the super-Earth from the star entirely. They turned the super-Earths into rogues. And now not a skeptical rogue but a rogue planet, which is cool too. We've covered rogue planets multiple times. For example, episode 800 had a nice news item on rogue planets. (Evan laughs) Now these are planets that can escape the gravity well, that have escaped the gravity well of their solar systems. Or perhaps they even formed by themselves without being tethered to any solar system. Any star of any kind. And they are likely out there in numbers rivaling the number of times Jay has said meatball on this show. Some estimates put the number of rogue planets in the Milky Way at 50 billion and probably a lot bigger than that potentially, but 50 billion is the number they're going with now. And many of them, you got to assume that a bunch of them are likely to be super-Earths. So what did the simulation say about rogue super-Earths? This is what they said. If you're a super-Earth rogue planet and you have five times the Earth's mass and you have an atmosphere 10,000 times more massive than the Earth's. Liquid water could survive on the surface of such a planet. 50 billion fracking years. 50 of such a planet could have liquid water for three and a half times the age of the universe. I mean, that just blew me. And I saw some numbers that were even larger. Somebody was throwing around 80 billion. But say 50 billion years of liquid water on the surface of a, of a super-Earth. That is incredible.

S: So what's the source of heat in that situation? Just internal? Just geothermal?

B: There wasn't any mention though of geothermal, radioactive decay, cause that's also kind of a classic source of energy for rogue planets in general. That are even Earth size. You can have subsurface liquid water because of this radioactive decay. But they really don't even mention radioactive decay in this research. But Steve, don't forget, the assumption here is that this atmosphere is 10,000 times more massive than the Earth's. That's amazingly massive. And apparently it's massive enough to hold in enough heat for a long time.

S: With what pressure? What would the surface, the atmospheric pressure be at the surface?

B: It would be similar to the pressure at the bottom of the ocean. Was one example. So you're walking on the surface that's what you're feeling. So yeah, if you're living on that surface, you're a hardy mofo. That's a hell of an environment.

S: Yeah but there could be organisms living in the water. Water on the surface of the super-Earth. There could be life in the water.

B: Yeah, absolutely. So now it made me think. Now life has had 4 billion years on Earth to evolve. And multicellular life has only had 600 million years. Now imagine the life that could evolve on such a planet. Now of course with some interesting selective pressures, of course. If you've got 50 billion years, what kind of life, what could biology be after evolving for many, many more times than the age of the universe? It's incredible. I would love to see a science fiction show that deal with this kind. I want to see some solid speculation. What could various different biologies accomplish in 50 billion years?

S: Yeah, I know, it's neat. It would be interesting to think about. It could be life on a habitable super-Earth rogue planet that's 10 billion years old.

B: Yeah, absolutely.

Who's That Noisy? (1:04:55)

S: Jay, it's who's that noisy time.

J: All right guys, last week I played this Noisy:

[increasing number of small animals chirping/twittering/squeaking]

All right guys, what do you think?

S: Some kind of critter.

E: Critters.

J: That's right, Evan. It is more than one critter.

E: Yes. Got it.

J: So a listener named Tim Savage wrote in said: "Hi Jay, long time listener, first time caller. Gotta say, I love the show and the Who's That Noisy segment." Of course you do. "My guess for this week's Noisy is parrots flocking to a lick in the Amazon rainforest". You guys know what a lick is?

S: Like a salt lick?

J: That's what I think. That makes sense.

B: Like an Amazonian rainforest version of McDonald's.

J: (laughs) So that's not correct. Another listener named Angela Frazier wrote in, said: "Guinea pigs very excited about carrots or other food". I have never heard excited guinea pigs but I bet you that they do sound similar to this Noisy. But that is not correct.

Visto Tutti wrote in, he said: "It sounds like a swarm of fruit bats, sometimes called flying foxes. They have some sonar sense, but it is low frequency and not very good. When fruit bats and possums get into a fight over tree ownership, it can be raucous".

We have a winner from last week. The winner is Robert Morehead and Robert said: "Hi Jay, this week's Who's That Noisy is two gangs of river otters about to throw down like West Side Story. That is correct. Two groups of otters who, I guess they call them gangs. And they're swimming towards each other and then a battle ensues. That happens. They get pissed. They'll bring switchblades. They don't mess around, man.

E: Oh, it's otter chaos.

J: (laughs) You bastard. Evan to celebrate you, I'm going to tell a dad joke that I heard.

E: Please.

J: Why can't you hear a pterodactyl go to the bathroom?

E: I don't know, Jay. Why can't I hear a pterodactyl go to the bathroom?

J: Because the P is silent.

E: Oh. (laughs)

J: I guarantee you hundreds of people tell that joke in the next day now. It's funny. It's funny, come on.

E: #silentP.

New Noisy (1:07:24)

J: All right. I have a new noisy for you guys this week. This Noisy was sent in by a listener named Marcel Janssens and here it is. And I will say that I believe at some point I have played a noisy that was similar to this one. Same principle, but it's been a very long time and this is one of my favorite kinds of noisies. So tell me what's going on in this sound. Ready?

[seeming old/amateur recording of discordant piano notes]

J: There it is.

E: Gee!

J: You must email me your guess at WTN@theskepticsguide.org. And don't forget, if you heard something cool, send it to me because I need to hear it.

Announcements (1:08:12)

J: Quickly Steve, the biggest thing on our plate right now is we have─

S: Two weeks.

J: ─NECSS 2022.

S: Just two weeks.

J: There's plenty of time to register. All you got to do is go to NECSS.org. We have all the information up there. I'll give you a little bit of intel. So because of scheduling situations, we had to prerecord the keynote. The keynote was between Bill Nye and David Copperfield. And they had over an hour conversation with each other and it really was fun. George was a part of that conversation and they talked about a lot of different things. They got into some personal information. This was one of the best keynotes we've ever had. It was a really interesting conversation. I hope that you join us this year. You can go to the website, check out all the other speakers that we're having. And don't forget that if you can't make it on August 5th and August 6th to the online live streaming conference, you could watch it for several months afterwards. So you could buy your tickets and watch it for up to three or four months after the conference actually airs. So you have access to it for a very long time. So please go to NECSS.org and join us this year.

S: Yeah, it's going to be fun. It's always a good conference. Obviously, we're going to be doing a live SGU recording in the middle of Saturday. I'm going to be having a conversation with Richard Wiseman. We're going to be talking about how come it's so easy to hack the brain with misinformation and disinformation. Coming from a neurology point of view, he's coming from a social psychology point of view. But it should be an interesting conversation. And we've got a ton of other great speakers lined up. We're going to do a Boomer versus Zoomer on Friday night. It's going to be one of our better conferences, I think. All right. Thank you, guys. We actually have a really fun interview coming up with Brian Dunning. So let's go to that interview now.

Interview with Brian Dunning (1:10:05)

S: Joining us now is Brian Dunning. Brian, welcome back to the Skeptics Guide.

BD: Thank you. It's been a long time.

B: Yeah.

J: How you've been doing, Brian?

S: So we're talking to you tonight because you have a project that you're working on that we want to chat about. The UFO Movie THEY Don't Want You to See..

BD: Emphasis on they, yes.

S: So who is they? Who is they?

BD: That's the big question everyone wants to know. And I say, that's why you got to watch the movie to find out.

E: Smart.

B: All right, then. My question is, this is some little YouTube video, right? That's what you're putting together, a little YouTube thing?

BD: No, this is another one of my series of actual movies designed to go on streaming services and be out there in the real world like big boy movies.

B: Excellent.

S: So it's going to be feature length?

BD: It's feature length and it'll be on all the usual streaming services. And unlike Science Friction, where we had some glitches getting that launched worldwide. This one will be available worldwide from the get-go because I know how to do that now.

S: Yeah. The learning curve is always wonderful. So this is an Indiegogo campaign. You're about 13% of the way through, but you talk as if it's a done deal. So is it possible this won't happen if you don't get the funding?

BD: No. There's a lot of different ways that you can cut corners. And I've made enough of these now that I know what you can cut, what you can't cut. It's fine. This is something that I'm producing myself out of pocket. And I've done really the one of the most expensive shoots has already been done. And most of the rest is going to be for things like insurance and stuff that depend on what distributor I go with. So depending on the insurance policy, that changes the spectrum of available distributors that you can work with. And there's big ticket items like original music. Hoping to do that. I've always worked with Lee Sanders, my good friend who's a great composer and does film scoring all the time. And I'm hoping to get him on this. But if I can't pay him a reasonable price, then it's just going to be canned music. Which I hate, but it works.

S: So you're going to do it no matter what. The budget will just determine how much you can do. How good it will be.

BD: Well, I think it's going to be good no matter what.

S: I said how good it will be, not if it will be good. (laughter) How awesome it will be.

B: Maybe how slick.

BD: Basically, there are production value choices that will change. But the content is going to be the same.

B: The meat will be there.

S: So let's talk about the meat. Now certainly feels like the right time for a movie like this. We're in the middle of a UFO flare.

B: Resurgence.

S: So tell us about what's going on.

BD: I mean, that was the driver for this project. At Skeptoid Media we're super spread thin this year. We've got so many projects going on. And we just hired a new director of operations, Kathy Wrightmayer, who you'll all meet if we ever have another conference in person anywhere in the world. And she's great. But basically, we couldn't do another movie this year like we wanted to start. And so I just talked with the board and said, look, we've got to do this UFO movie now. And we just decided if it's going to happen, it's going to be something that I have to do on my own without sucking up Skeptoid resources. So that's how it is the way it is. But that indicates how timely this issue is. This movie needs to be made now because we've got these ridiculous hearings in Congress, for God's sake, where you've got Congress people talking about UFOs representing national security threats. UFOs shutting down our nuclear arsenal. And all these things that there is actual science that we can discuss here. And I think once we do, that a lot of people see that some of this attention is not necessarily being very appropriately applied.

S: Yeah, it's really something feels a little bit different about this time. I think it's tipped up into like the mainstream media is taking it more seriously than they should. I think because the Pentagon, rather than just like nothing to see here, they're actually being more open about it. But they're not doing a good job of communicating what's really going on and what's not going on. They're doing that thing like there is no evidence to say that there is aliens,. But they're saying in such a way that it's like but they're not closing the door on it. Or they're not really giving a good, they're not characterizing the evidence in a meaningful way. They're just being coy.

J: They're not science communicators. What they don't realize is they are completely baiting conspiracy theorists.

S: Totally.

J: Guys, could you imagine, go back 15-20 years when we were all in our early days of skepticism. Could you imagine us thinking, hey, guys, in 15 to 20 years, we're going to be having a discussion about a resurgence of UFO enthusiasm? I wouldn't believe it.

S: I would. This always goes through cycles.

B: It's almost as bad as Bigfoot.